A wolverine (public domain)

It's always a great feeling when the lost is found, when a mystery is solved – and especially so when the lost had been lost, and the mystery concerning it unresolved, for over 40 years.

Right from a very early age, I had always been fascinated by mysterious and mythological creatures, making my eventual cryptozoological career little short of inevitable. And so it was that a certain episode of a Western show that my family and I viewed one Sunday afternoon on British television during the mid-1960s, when I was around six years old, engaged my attention to a far greater degree than might otherwise have been expected, given the fact that, normally, the Western genre held little if any interest for me.

The episode in question concerned the stalking of a family living alone in the American wilds a century or so ago by a mystifying but greatly-feared beast of such rapacious, belligerent, yet elusive nature that it was referred to superstitiously by the local native American people as a devil (a name that, as far as I could recall, also featured in the title of this episode). They also called it by another, more exotic-sounding name, and, as in all the best suspense movies, the creature itself was never seen, until the very end. Instead, the viewer had to be content with savage growls, rustles in the undergrowth, and off-screen activity.

Finally, the 'devil' was lured close enough to be shot, and at the denouement it was revealed to be an unexpectedly large specimen of a creature not generally encountered in those parts. But what exactly was that creature? Only at the end was its English name finally given, and it proved to be a species that, as a young child, I had never heard of before – the wolverine.

|

| The wolverine, painted by John James Audubon |

Known scientifically as Gulo gulo, native to boreal forests in northern North America and also northern Europe and northernmost Asia, the wolverine or glutton is the largest living terrestrial member of the mustelid family, growing to the size of a small bear. Moreover, it is infamously ferocious, powerful, intelligent, and tenacious, making it one of the most feared species of mammal throughout its range. Little wonder, then, that in the episode it had been referred to by the native people as a devil.

|

| Beware the wolverine, my son! (with apologies to Lewis Carroll!) |

This particular programme had a strong impact on me, as I had been enthralled waiting to discover what the mystery beast in it was, and I can remember watching it avidly a second time a couple of years or so later when the series in which it appeared was repeated on television (even though I now knew the creature's identity beforehand), but after that, nothing. As far as I am aware, neither the entire series nor this particular episode from it was ever broadcast on British television again. But what was the series?

|

| Wolverine postcard from my collection (Norfolk Wildlife Park) |

The years passed by, and despite remembering the wolverine episode in great detail, I never could recall the name of the series itself, and whenever memories of the episode periodically came to mind I always promised myself that I'd pursue this intriguing little mystery, but somehow I never did. Eventually, even the wolverine episode faded in my recollection until it became little more than a hazy, half-forgotten dream. And although I would often flick through books on vintage television, I never obtained any clues as to its series' identity.

Just like its subject, however, the wolverine episode was nothing if not tenacious, and recently it came to mind yet again – but now, armed with the vast research power of the internet, I decided that the time had come to track down this cryptozoological tele-phantom once and for all. I began my search on YouTube, in the hope that the episode, or at least an excerpt or two from it, had been posted there. I knew that I could still remember enough details to be able to recognise it, should it be there. But despite using a variety of key words – 'Western', 'television', 'wolverine', 'devil', '1960s' – nothing promising came up.

|

| Wolverine at the Arctic Interagency Visitor Center, Coldfoot, Alaska |

So I turned my attention to Google, and used the same key words in its search engine. After a time, I thought I'd discovered it, but it was a false lead. Google had turned up an episode from 1963 called 'The Wolverine' in a Canadian series entitled 'The Forest Rangers', in which a ferocious wolverine turns up in Indian River (the fictional location where this series was set), killing all the livestock there. This plotline certainly compared closely with the programme that I had seen, and the creature was even referred to in it by the same exotic name that I now recalled from 'my' episode – carcajou, an Ojibway name. But when I researched 'The Forest Rangers' series, I discovered that its rangers-focused storylines didn't accord at all with those of the series that I had viewed all those years ago. Exit 'The Forest Rangers'.

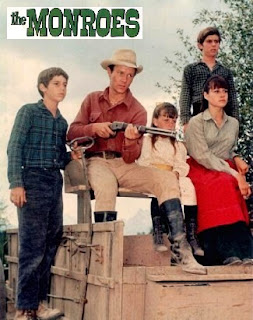

Happily, however, my continued Googling did finally achieve the long-awaited success that I had been hoping for, because there, at last, on my computer screen, was the answer. The series, first broadcast in 1966, was entitled 'The Monroes', which was produced by Qualis in association with 20th Century Fox Television, and included Michael Anderson Jr and Barbara Hershey (playing the parent-substitute figures of big brother and sister) among its stars.

It centred around the story of five orphans (aged from 18 down to 6 years of age) trying to survive in 1876 as a family on the frontier in the area around what is now Grand Teton National Park near Jackson, Wyoming, after their father and mother had drowned.

|

| An official story book companion to 'The Monroes' (TheDamnÐœushroom/Flickr) |

Running for just a single season, 'The Monroes' consisted of 26 episodes – the fourth of which, entitled 'The Forest Devil', was the wolverine episode that had played such a key role in kindling my interest in cryptozoology as a youngster and had afterwards teased and tantalised my mind for over four decades.

And as if my solving this longstanding mystery from my childhood was not satisfying enough, I then discovered that the entire episode had actually been uploaded on YouTube, in five parts. Needless to say, and for the first time since the mid-1960s, I duly sat back and watched 'The Forest Devil' – an experience made even more memorable this time by being able to view it in colour. For just like so many other families in Britain at that time, we'd only owned a black-and-white television during the 1960s, so until now I'd never seen this programme in colour.

Returning when an adult to a television show, a book, or even a location that had been so appealing as a child does not always live up to expectations, with the memory of it sometimes proving to have been much more special than the reality. However, I'm happy to report that in the case of 'The Forest Devil', it was every bit as thrilling and enjoyable now, even in these jaded 2010s, as it had been for me back in the 1960s, when everything was still bright and fresh and new and exciting.

In terms of cryptozoological significance, rediscovering 'The Forest Devil' hardly compares, for instance, with my recent solving of the long-baffling Trunko case, nor would it rank alongside the refinding of the legendary thunderbird photograph (should this ever happen one day), but, for me, it was just as eventful and satisfying. It also showed me that miracles, even if they are only very minor, personal ones, do indeed still happen in this mundane old world of ours. And that is something else well worth treasuring.

If you'd like to view 'The Forest Devil' on YouTube, here it is in five clickable parts:

'The Forest Devil', Part 1

'The Forest Devil', Part 2

'The Forest Devil', Part 3

'The Forest Devil', Part 4

'The Forest Devil', Part 5

UPDATE: The above 5 parts are no longer on YouTube, but as of 24 January 2021 the entire episode in complete form is accessible here.