An unofficial, personal interpretation of the hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Richard Svensson) and a representation of the Mongolian death worm based upon eyewitness accounts (Ivan Mackerle)

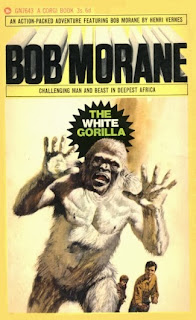

The works of J.R.R. Tolkien contain a number of creatures with some pertinence to cryptozoology, such as giant spiders, dragons, and the dreaded watcher in the water (a monstrous freshwater cephalopod?). Yet perhaps the most unexpected as well as the most fascinating Tolkien reference to a cryptid, which occurs in The Hobbit (1937), is so brief and inconspicuous that it can be easily passed by or even entirely overlooked, with its cryptozoological significance not even registering upon the reader. This is a great tragedy, because, remarkable as it may seem, the mystery beast in question is none other than the extraordinary Mongolian death worm!

J.R.R. Tolkien, aged 24, photographed in 1916 when a soldier in the British Army during World War I (Public domain/Wikipedia)

In 'An Unexpected Party', which is the opening chapter of The Hobbit, the hobbit in question, Bilbo Baggins, has received an unexpected visit at his home, Bag End, from the wizard Gandalf and a company of dwarves, whom Gandalf has informed would do well to include Bilbo, as a burglar, in their planned quest to retrieve their stolen gold from the great dragon Smaug. The dwarves, however, are far from convinced that Bilbo would be serve well in this capacity, and they air their doubts very vocally in Bilbo's parlour while he is in the drawing-room (but, unbeknownst to them, still within ear-shot of their protestations). Angered by their dismissive attitude, Bilbo strides back into the parlour, and boldly proclaims that he is more than capable of fulfilling the role that they wish him to undertake:

Tell me what you want done, and I will try it, if I have to walk from here to the East of East and fight the wild Were-worms in the Last Desert…

Brave words indeed, but also very puzzling ones, because they are never explained nor even referred to ever again either within this or any other Tolkien novel. They are presumably said by Bilbo in a figurative sense, to convey that he is willing to tackle anything. But even so, what exactly are the wild Were-worms that they refer to, and where was the Last Desert?

An earthworm

The term 'worm' has a number of different zoological and zoomythological meanings. Its most familiar zoological meaning is as a contraction of 'earthworm' – the common name for most terrestrial oligochaetes. However, many other, unrelated zoological invertebrate taxa that include long, elongate species also have 'worm' in their names – tapeworms, peanut worms, acorn worms, beardworms, thorny-headed worms, ragworms, roundworms, flatworms, etc etc. There are even a few worm-dubbed vertebrates, such as the slow worm Anguis fragilis (a species of limbless lizard).

In zoomythology, 'worm' is one of several related terms – others include 'orm', 'ormer', and 'wyrm' – applied to certain serpent dragons (i.e. limbless, wingless dragons that basically resemble huge serpents except for their dragon-like head), such as Britain's Lambton worm, Linton worm, and Kellington worm. This category of dragon was also often characterised by noxious breath (rather than breathing fire), and the ability to rejoin into a single entity again if cut up into segments.

In Tolkien's works, conversely, he applies the term 'worm' to a very elongate-bodied form of classical dragon, i.e. equipped with four legs, a pair of wings, and the ability to breathe fire. Smaug in The Hobbit was a prime example of Tolkien's dracontological definition of 'worm'.

My trusty 40-year-old copy of The Hobbit, featuring an early sketch by Tolkien himself of the worm Smaug on its cover (illustration © Unwin Books)

Consequently, the were-worm may be a bona fide type of invertebrate worm, albeit one of formidable size and/or temperament if it warranted being fought against (as opposed merely to being trodden upon!); or it could be a Smaug-like dragon. But what about the 'were' component of its name?

This prefix, from the Old English 'wer', generally denotes 'human' - hence a werewolf, for instance, is a human that can transform itself into a wolf, a weretiger is a human that can transform itself into a tiger, and so on. Does this mean, therefore, that a were-worm is a human that can transform itself either into a gigantic invertebrate-type worm or, perhaps more plausibly, into a dragon? Alternatively, is it a true invertebrate-type worm, or a true dragon, but one that exhibits highly advanced, human-like intelligence? Or could it even refer to a being that was half-human, half-dragon, akin in form perhaps to the ancient Indian snake deities or nagas, which possessed human heads (and sometimes thorax and arms too) but serpent bodies? Any of these solutions, however, would involve an entity of truly monstrous nature.

Figurine of a female naga, or nagini (Dr Karl Shuker)

As for the Last Desert, where these were-worms reputedly dwell: all that appears to be known about this arid realm is that according to hobbit folklore, it is located at the very easternmost end of Middle-earth, and therefore lies far to the east of the Shire where the hobbits live.

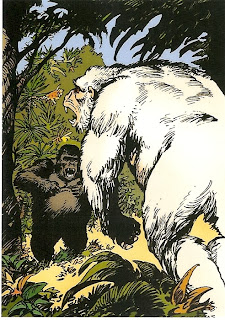

But where does the Mongolian death worm fit into all of this? As any self-respecting cryptozoologist will know, this much-dreaded cryptid allegedly inhabits the Gobi Desert, and according to the nomads living in fear of it there, it can not only squirt a lethal acidic venom at anyone confronting it, but also kill directly via touch (or even indirectly if a person touches it with an implement made of metal) in a mysterious manner that is extraordinarily reminiscent of electrocution.

Another representation of the Mongolian death worm (Thomas Finley)

Yet even the versatile death worm cannot transform into a human or vice-versa. So what connection can there be between this cryptid and Tolkien's were-worm, other than that they both inhabit deserts?

A comprehensive two-volume study of The Hobbit, entitled The History of The Hobbit, Mr Baggins, was published in 2007 by HarperCollins in the UK (and by Houghton Mifflin in the USA), containing Tolkien's unpublished drafts of The Hobbit, together with commentary written by Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff. These drafts revealed how this novel had undergone many changes, some minor, some major, between the very first version and the final, published edition. One such change is of paramount important to the subject of this ShukerNature post, because it concerns Bilbo's statement regarding the were-worms.

It turns out that in the very first, original draft of The Hobbit, that statement made no mention at all of were-worms, or of the Last Desert. Instead, what it did state, very thought-provokingly, is as follows:

[that Bilbo would walk to] the Great Desert of Gobi and fight the Wild Wire worms of the Chinese.

How remarkable that the Last Desert as named in the final, published edition of The Hobbit was clearly inspired, therefore, by none other than the real-life Gobi Desert. And no less significant is that the ostensibly shape-shifting were-worm was apparently no such thing in the original draft of The Hobbit, being a wire-worm instead. But what did this term signify?

An Oriental dragon

In view of the reference to the Chinese, could it have referred to one of those famously serpentine-bodied Oriental dragons? However, they tend to waft languorously through the skies, or rise up from the seas or from deep freshwater pools, rather than reside in deserts, and are often viewed in ancient Eastern traditions as deities. So this identity for Tolkien's wild wire worms seems somewhat unlikely. And why, in any case, would he have applied the adjective 'wire' to such dragons?

Certainly, the term 'wire worm' is intriguing, inasmuch as in zoological parlance a wire worm is the elongate limbless worm-like larva of a click beetle, belonging to the family Elateridae. But I hardly think that Tolkien was referring to some hobbit-inimical, hyper-aggressive click beetle grub when writing of 'Wild Wire worms'.

Two species of click beetle and their respective wire worm larval form

All of which brings us, therefore, to the Mongolian death worm. This cryptozoological creature has definitely – indeed, exclusively – been reported from the Gobi Desert, and is undeniably zoologically worm-like in overall appearance (its local names, allergorhai-horhai and allghoi-khorkhoi, both translate as 'intestine worm', as it is likened by the nomads to a worm that resembles an animate intestine). But is it conceivable that Tolkien had heard of such an entity, especially way back in the 1930s? After all, Western cryptozoology itself did not become aware of it until the 1990s, when Czech explorer Ivan Mackerle began searching for and writing about the Gobi's reputed inhabitant after having researched its history in Russian and Mongolian documents.

Wood carving of a death worm-like creature in Gobi museum near Dalanzadgad, Mongolia (Ivan Mackerle)

Nevertheless, Tolkien, as a highly erudite, eclectic reader, may indeed have known of such a beast, thanks to the publication in 1926 of On the Trail of Ancient Man, written by eminent American palaeontologist Prof. Roy Chapman Andrews. This bestselling book concerns the American Museum of Natural History's famous Central Asiatic Expedition of 1922 to the Gobi, led by Prof. Andrews, in search of dinosaur fossils, but it also includes a mention of the Mongolian death worm – which as far as I am aware is the earliest such mention of it in any Western publication.

In order to obtain the necessary permits for the expedition to venture forth into the Gobi, Andrews needed to meet the Mongolian Cabinet at the Foreign Office. When he arrived, he discovered that numerous officials were attending their meeting, including the Mongolian Premier. After Andrews had signed the required agreement in order to obtain the expedition's permits, the Premier made one final but very unusual and totally unexpected request:

Then the Premier asked that, if it were possible, I should capture for the Mongolian government a specimen of the allergorhai-horhai. I doubt whether any of my scientific readers can identify this animal. I could, because I had heard of it often. None of those present ever had seen the creature, but they all firmly believed in its existence and described it minutely. It is shaped like a sausage about two feet long, has no head nor legs and is so poisonous that merely to touch it means instant death. It lives in the most desolate parts of the Gobi Desert, whither we were going. To the Mongols it seems to be what the dragon is to the Chinese. The Premier said that, although he had never seen it himself, he knew a man who had and had lived to tell the tale. Then a Cabinet Minister stated that "the cousin of his late wife's sister" had also seen it. I promised to produce the allergorhai-horhai if we chanced to cross its path, and explained how it could be seized by means of long steel collecting forceps; moreover, I could wear dark glasses, so that the disastrous effects of even looking at so poisonous a creature would be neutralized. The meeting adjourned with the best of feeling.

Call me a cynic, but I have the distinct impression that Prof. Andrews did not take the death worm too seriously. In any event, he certainly didn't succeed in finding one, which is probably no bad thing - bearing in mind that he had planned to pick up with steel forceps a creature that had allegedly killed a fellow geologist who had prodded it with a metal rod!

Prof. Roy Chapman Andrews (George Grantham Bain Collection/USA Library of Congress/Wikipedia)

During the 1920s, the American Museum of Natural History sent forth several additional Central Asiatic Expeditions to Mongolia and China, and in 1932 a major work, The New Conquest of Central Asia, was published, documenting all of them, with Prof. Andrews as its principal author. The first volume in the series Natural History of Central Asia (edited by Dr Chester A. Reeds), it contained a brief section entitled 'The Allergorhai Horhai':

At the Cabinet meeting the Premier asked that I should capture for the Mongolian Government a specimen of the Allergorhai horhai. This is probably an entirely mythical animal, but it may have some little basis in fact, for every northern Mongol firmly believes in it and will give essentially the same description. It is said to be about two feet long, the body shaped like a sausage, and to have no head or legs; it is so poisonous that even to touch it means instant death. It is reported to live in the most arid, sandy regions of the western Gobi. What reptile can have furnished the basis for the description is a mystery!

I have never yet found a Mongol who was willing to admit that he had actually seen it himself, although dozens say they know men who have. Moreover, whenever we went to a region which was said to be a favorite habitat of the beast, the Mongols at that particular spot said that it could be found in abundance a few miles away. Were not the belief in its existence so firm and general, I would dismiss it as a myth. I report it here with the hope that future explorers of the Gobi may have better success than we had in running to earth the Allergorhai horhai.

If Tolkien had read either or both of these books, and as someone passionately interested in archaeology it is by no means an unlikely possibility, then he would indeed have learnt of the dreaded death worm, whose sensational nature might very well have impressed him sufficiently to incorporate a version of this creature in his first draft of The Hobbit. Moreover, Andrews's comparison of the death worm's significance to the Mongolian people with that of the dragon to the Chinese may even have inspired Tolkien's otherwise-opaque linking of the wild wire worms to the Chinese.

Dr Jarda Prokopec and Ivan Mackerle seeking the Mongolian death worm in the Gobi Desert (Ivan Mackerle)

As for why the wild wire worms were replaced in later drafts by wild were-worms, and the Gobi Desert replaced by the Last Desert, who can say? Perhaps Tolkien felt that the latter versions were more compatible with the entirely fictitious Middle-earth than were a real desert and a semi(?)-mythical creature from Mongolian tradition referenced to in a real scientific publication.

Of course, this is all very speculative, as there is no firm evidence that Tolkien ever did read or even know of Andrews's above books, but that memorable sentence in Tolkien's original draft of The Hobbit remains a compelling enigma. And if nothing else, it conjures up the truly surreal scenario of a hobbit doing battle with the Mongolian death worm – which is surely worthy of a novel in its own right!

This

ShukerNature post is excerpted from one of my current books-in-progress – The

Mongolian Death Worm: Do Nomads Dream of Electric Worms? Philip K. Dick and

'Blade Runner' aficionados will need no explanation of my book's subtitle!

For the most comprehensive documentation of the Mongolian death worm ever published, see my book The Beasts That Hide From Man (Paraview: New York, 2003).