Three

(un)usual suspects as the identity of the Shatt-al-Arab's venomous mystery fish

– the Asian stinging catfish (top); the long-tailed moray eel (centre), and the

bull shark (bottom) (public domain)

Yesterday, here

on ShukerNature, I offered a blenny for your thoughts (click here). So today, I'm offering another one! You can

thank me later.

The

Shatt-al-Arab is a 120-mile-long river formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the

southern Iraq town of Al-Qurnah. Flowing

southwards, it constitutes the physical border of Iraq with Iran, and empties

into the Persian Gulf. Many species of fish inhabit its waters,

but one of them may be a notable species still unknown to science.

I first learnt

of this small but potentially significant unidentified freshwater fish many

years ago, when reading Dangerous To Man (1975), Roger Caras's

definitive book on creatures hostile to humans, but its mystery remains

unsolved to this day. In his book, Caras included the following brief but very

intriguing paragraph:

From Tehran comes a

report of a diminutive black fish found in the Shatt al Arab River. It

reputedly has killed twenty-eight people with a venomous bite. Death is

said to be swift. No other information is presently available. (No other fish

is known to have a venomous bite, and this report is at least suspect.)

What makes the

above snippet so interesting (apart from the fact that except for my own

researches into it and documentation of it in various of my books and articles,

I have never encountered anything more about this creature anywhere) is Caras's

claim that it is its bite that is venomous and that no other fish is known to

have a venomous bite. In contrast, a wide range of piscean species possess

venomous spines, for instance, or toxin-secreting skin.

My

copy of Dangerous To Man by Roger Caras (© Roger Caras; reproduced here

on a strictly non-commercial, Fair Use basis only)

But if we assume

that such a fish does indeed exist, what could it be, and how can its reputedly

venomous nature be explained? Various candidates can be selected from the many

thousands of fish species already known to science, but none can offer a

comprehensively satisfying solution.

When I

originally read Caras's report, the first candidate that came to mind, for

several reasons, was the Asian stinging catfish Heteropneustes [formerly

Saccobranchus] fossilis. This species does indeed inhabit the

Shatt-al-Arab (though it is an imported rather than a native fish here, originating

from Indochina). Moreover, it is often only around 4

in long (though it can grow up to 1

ft), it is definitely black in colour, and, of particular

significance, it is known to be venomous. So far, so good.

However, unlike

the Shatt-al-Arab mystery fish, the Asian stinging catfish is venomous due not

to a toxic bite but instead to a poison gland at the base of a spine on each of

its two pectoral fins. This can yield an extremely painful but not fatal sting.

Consequently, even if victims (or onlookers) were mistaken in assuming that

this catfish had bitten them (unless perhaps it had done so in self-defence if

they had been molesting it, but this would not have been a source of venom),

they would not have died from its fin spines' sting. Exit H. fossilis

from further consideration.

A second

candidate is the long-tailed or slender giant moray eel Strophidon sathete

(aka Thyrsoidea macrura). Although typically marine, and distributed

widely in the tropical Indo-Pacific Ocean, it is well

known for entering estuaries and travelling considerable distances up rivers,

including the Shatt-al-Arab. What is particularly interesting about this

species in relation to the latter river's mystery fish is that in a sense it

can be said to have a toxic bite, albeit not in the usual convention.

True, its teeth

do not actually secrete a toxin, via poison sacs, like those of venomous

reptiles do. However, as a voracious carnivore the long-tailed moray eel will

certainly have pieces of rotting flesh left over from previous meals and packed

with pathogenic bacteria sticking to its teeth, just like crocodiles and

carnivorous mammals like lions and tigers do. Consequently, a bite from this

fish might well transfer some of those bacteria into the wound caused by its

teeth, which in turn may lead to septicaemia developing, especially in someone

with a less than robust immune system, such as a child, an elderly person, or

someone recovering from a major illness. Even so, no known human fatalities

resulting from a bite by this moray eel species are on record, and there is

also the not-inconsiderable problem of size difference to reconcile, because it

can attain a maximum length of up to 12

ft when fully grown (even its average length is over 2

ft). So this species can hardly be deemed 'diminutive', like the

Shatt-al-Arab mystery fish. Don't call us, S. sathete.

Nor can the bull

shark Carcharhinus leucas be termed diminutive, bearing in mind that it averages

7.5 ft long. Unlike

most sharks, this notably aggressive species is frequently found in freshwater

habitats, including the Shatt-al-Arab River, and like those

of moray eels its teeth are brimming with pathogenic bacteria from rotting meat

still attached from earlier meals. So again, a bite from this fish, although

not intrinsically venomous, might well lead to blood poisoning. And several

human deaths caused by this fish attacking them have been confirmed here. But

as even a new-born specimen is normally around 2.5

ft long, this species clearly has no bearing upon the identity of

the Shatt-al-Arab mystery fish.

As I researched

further into this ichthyological puzzle, however, I made an unexpected

breakthrough, by discovering that one crucial aspect of Caras's account was

fundamentally incorrect. Contrary to his statement, some fishes do

possess a genuinely venomous bite.

And one of these

is the blackline fang blenny Meiacanthus nigrolineatus. Its lower jaw

bears sizeable canine teeth that have grooved sides and venom-producing tissue

at their base. These teeth enable it to produce a sufficiently unpleasant bite to

deter all predatory fishes, large and small. In general appearance, it is

relatively nondescript – no more than 3.75

in long, with a blue-grey head and foreparts, and the remainder of

its body pale yellow. There is also a thin black stripe running lengthwise just

beneath its dorsal fin, which earns it its common name.

Blackline

fang blenny (© Akvariumugamyba at http://akvariumugamyba.lt/ - reproduced here

on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Over 830 species

of true blenny or blennioid are currently known to science, generally small in

size and scaleless but many-toothed, and are of worldwide distribution. Most

are marine fishes, as indeed is the blackline fang blenny, which is native to

the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez and Aqaba.

However, there are freshwater species too (such as the well-known Salaria

fluviatilis, which is native to rivers in several European countries as well

as in Morocco, Algeria, Israel, and Turkey).

No human

fatalities have been recorded with the blackline fang blenny, but what if the Shatt-al-Arab River is harbouring a

still-undescribed, darker-coloured, but otherwise comparable freshwater

relative that is capable of producing a more potent venom? If such a creature, known

locally but attracting little notice from the outside, scientific world, is one

day captured and formally identified, then our mystery fish will surely have

been unmasked at last - turning up like the bad blenny that it is.

My special

thanks to French ichthyologist Dr François de Sarre for very kindly sharing his

own thoughts and comments with me regarding this fishy affair.

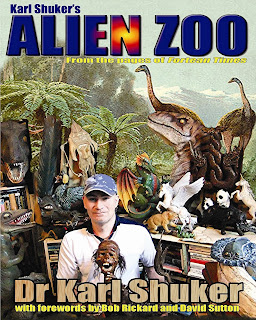

This ShukerNature blog article is adapted and

expanded from my book Karl Shuker's Alien Zoo: From the Pages of Fortean Times.