The

dramatic, climactic panel from the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The

Monster of Dread End' written by John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that

first appeared in Ghost Stories, #1,

September/October 1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced

here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review

purposes only)

As today has been yet another Bank

Holiday Monday of the traditional wet'n'windy, stay-at-home type here in the

UK, by way of light(?) relief I'll share with you tonight on ShukerNature a

notable cryptozoology-relevant rediscovery made by me during the early hours of

this morning. True, its subject certainly may not be notable to everyone, nor

may it be what everyone would instantly or at least initially deem to be of

cryptozoological relevance. However, my finding of it today almost by chance after

having purposefully and diligently searched so many times before yet always in

vain swiftly reminded me of how, in spite of its overtly bizarre nature, this very

specific, never-forgotten item may well have played a subtle role in cultivating

my curiosity about monsters and mystery beasts as a child, inputting only too memorably

into the formative mind of a fledgling cryptozoologist the excitement as well

as even sometimes the terror associated with such creatures. And the name of

this unconventional yet indelibly imprinted source of proto-cryptozoological

intrigue? The Monster of Dread End. But to begin at the beginning…

Sometime during the late 1960s or early

1970s, I was bought a very unusual hardback comic book. In outward appearance,

it greatly resembled the familiar comic annuals that used to be produced for

sale just before Christmas each year by all of the major British children's

comics, a fair selection of which I would buy or have bought for me at one time

or another down through my younger years. These included such fondly-remembered

but long-since vanished titles as The

Beezer, The Dandy, The Topper, The Beano (sole survivor today), Sparky, Buster, Cor!, Whizzer & Chips, The

Eagle, Valiant, Lion, Tiger, and Jag. However,

the contents of the annual-type comic book under consideration here were very

different from the innocuous cartoon humour and 'boys-own' adventure serials

present in those above-named titles. Indeed, to the impressionable, highly

imaginative youngster that I was back then, they were for the most part quite

nightmarish, even horrific, and I freely confess that unbidden thoughts about

them gave me a fair few sleepless nights as time went on. This no doubt

explains why I eventually discarded the book, about 2-3 years after having

received it, but even today I can still vividly recall a fair amount of its

contents, although I can neither remember its title nor its front-cover

illustration.

About 64 pages long and A4-sized, this

annual-lookalike comic book contained a series of self-contained stories

(somewhere around 10-12, if I remember correctly), each one presented in the

traditional panel-type illustration format of comic strips. Some were in full

colour, others in monochrome, although red/white was favoured over b/w, as far

as I can recall. However, their one common attribute was that the theme of

their stories was the supernatural and the unknown, presenting a diversity of fictitious

but terrifying tales featuring the likes of malevolent phantoms and other

malign presences, fatal premonitions, and monsters – including the

afore-mentioned denizen of Dread End, which irresistibly captured in its

hideous clawed grasp the near-mesmerized attention and tenacious, abiding

remembrance of this youngster just as surely and unrelentingly as it did

physically to the numerous children who were its doomed victims in the story.

(Incidentally, I should note here that until

this morning's rediscovery I'd completely forgotten that this story's title was

'The Monster of Dread End', having readily remembered its plot and pictures

down through the decades but not what it was actually called, which is why I'd

experienced such problems in the past when seeking it out. Consequently, I'd

concentrated my efforts instead upon trying to recall the title of the book

containing it, entering all manner of word combinations into Google's search

engine and image search in the hope of assembling a phrase close enough to the

book's title for details to appear concerning it and/or a picture of its cover

that might elicit some recollections, but nothing ever did. This morning,

however, I tried a different tactic, but one that worked immediately. I simply

entered 'giant hand sewers comic book' into Google Image's search engine, and up

popped several panels from that still very familiar story, together with its

hitherto-forgotten title and plenty of other details too, which will be

revealed later.) Anyway, back to the story.

The

very atmospheric opening panel from the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The Monster of Dread

End' written by John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that first appeared

in Ghost Stories, #1,

September/October 1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced

here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review

purposes only)

Set in an unnamed American town or city

suburb, 'The Monster of Dread End' begins with the above-reproduced panel

depicting and describing the dismal, derelict tenement blocks of Dread End,

long since deserted and cordoned off with an official Keep Out sign attached to

the chains encircling this accursed street and its immediate environs. The next

few panels provide harrowing flashbacks that reveal how the horrors now

inextricably associated with it began. Back then, Dread End was a bustling,

happy street called Hawthorn Place – until that fateful early morning when a

dead "balled-up thing" was found there, lying on the pavement

"like an empty wrapper thrown carelessly aside but somehow still recognizable

as having once been human". (Mercifully, no actual image of this object was

presented, only the above-quoted description of it, so exactly what it looked

like was left to the reader's imagination.) At the same time that horrified

observers were gathering around it to stare in shock and revulsion, a panic-stricken

young boy came running out of his family's apartment, yelling to everyone that

his kid sister had gone missing, her bed empty…

Within a relatively short space of time,

several other children from families living in Hawthorn Place also went missing

from their beds. On each occasion, their absence was soon followed that same

morning by the discovery close by of another of those horrific dead objects,

lying on the street in silent, abject testimony to the fully-formed, living,

loving child that had formerly existed in its stead. Even when frightened

parents boarded up the windows in their children's bedrooms, the anomalous abductions

continued, the boards being discovered broken and torn aside, the children

gone, and the "balled-up things" found on the pavement nearby.

Consequently, it was not long before the street's residents had all moved out,

even those with nowhere else to go, content to live on the streets elsewhere if

need be rather than remain in their homes and face the unexplained horror of

Hawthorn Place. For despite all of their efforts, not only the local police but

also the best criminological brains in the business called in from elsewhere

were completely unable to discover who – or what – was responsible for this

trail of terror and death.

Years went by, and Hawthorn Place, now

redubbed Dread End due to its infamy, became encircled by other empty streets,

yielding a veritable domain of the damned, a no-man's land of the lost, because

no-one wanted to live even close to, let alone within, this sinister street.

Nor did anyone ever set foot near it – until one particular night. That was

when teenager Jimmy White ventured alone into the grim, dark shadows of Dread

End in search of an answer to its foul mystery, seeking the cryptic Monster of

Dread End itself, whatever or whoever it may be – because seven years earlier,

he had been that panic-stricken young boy who had run outside shouting that his

kid sister was missing, her bed empty. She had been the Monster's first victim,

her remains being the first of those horrific "balled-up things".

Jimmy had vowed vengeance ever since, and now he was here to take that

vengeance, although, armed with nothing more than a police whistle with which he hoped to

alert any cops who may be patrolling other streets in the vicinity if he should actually encounter

his quarry, he was by no means clear about how to do so. Nevertheless, he

intended to try, somehow, for his sister.

Hours later, however, with nothing seen

or heard, Jimmy conceded to himself that he was probably years too late, that

the culprit had no doubt moved on long ago. Yawning and stretching in the first

light of dawn, he was just about to do the same, when suddenly, causing him to

freeze in mid-stretch, a nearby manhole cover began to rise, then slipped to

one side – as a huge five-fingered long-clawed hand covered in livid-green

reptilian skin slowly emerged, followed by an unimaginably lengthy,

similarly-scaly arm. Were it not for it terminating in that grotesque taloned

hand instead of a head, the arm would have resembled an anaconda-like snake, as

more and more of its immensely flexible, serpentine form continued to emerge.

While an unbelieving Jimmy watched in absolute horror, standing stock-still for

fear of alerting this obscene, repellent entity to his presence, the hand and

arm rose up against the wall of a building close by, stretching ever upwards,

feeling, searching, blind but evidently sentient, and quite obviously seeking

prey.

Seeking

prey – a panel from the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The Monster of

Dread End' written by John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that first

appeared in Ghost Stories, #1,

September/October 1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced

here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review

purposes only)

Jimmy had no idea what it was or where it

had originated, but in that moment he knew with absolute certainty that he had

solved the mystery of all of those missing children's gruesome fates, including

that of his sister. They had been seized in their beds by this vile

abomination, which had been lurking in the sewers of Dread End, and was still

living there today, emerging at daybreak in the hope of abducting further

victims to sustain its foul existence.

In his shock at what he had just seen, Jimmy

lost his grip on his whistle, which fell to the ground, clattering on the

pavement. Instantly, the hand and arm shot back down inside the manhole with

lightning speed. So although it couldn’t see, this eerie entity could certainly

sense the vibration of Jimmy's whistle hitting the floor. That must have been

how it had traced its young victims, sensing the subtle vibrations that they

had made while lying asleep in their beds all those years ago.

Alone once more amid the foreboding,

unnatural silence of Dread End, Jimmy started debating with himself whether

he'd be able to escape if he fled, or whether the monster would re-emerge and grab him straight away if it sensed his

movements. Yet even before he had chance to come to a decision, that terrible

clawed hand and snake-like arm did indeed emerge – and this time it was moving

directly towards him! Again, Jimmy froze, not moving a muscle as the hand groped

ever closer, ever nearer to his shadow-concealed form squatting in a dead-end

alley. But then it paused, and moved instead towards an open, lidless dustbin

(or garbage can to my US readers), lying on the ground right next to Jimmy. Its

taloned fingers reached inside, but found nothing there, so as if in impotent

rage the hand grasped the bin, and closed its fingers around it, crushing it as

if it were made of tissue.

Nevertheless, the bin had apparently

distracted the monster's attention from Jimmy, because instead of turning back

towards him, the hand and arm, still emerging in seemingly limitless length

from the manhole, moved off, groping blindly along a street leading away from

the petrified teenager. What to do now? Jimmy stayed squatting in the dead-end

alley, figuring that the more of this monster that emerged and moved on down

the street, the further away from him its deadly hand would be – until a

sixth-sense survival instinct suddenly kicked in. Jimmy looked behind him – and

looming directly above him was the hand! Unbeknownst to Jimmy, it had entered a

window in a tenement block further down the street, and by a series of sinuous,

silent loops of its immensely lengthy, flexible arm in and out of other windows

the hand had cunningly doubled back towards Jimmy and had finally emerged from

a window overlooking the very alley in which he was crouching!

It's

behind you! A panel from

the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The Monster of Dread End' written by

John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that first appeared in Ghost Stories, #1, September/October

1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

The hand lunged down at Jimmy, but the

youth was able to dodge its terrible clawed fingers, yet found himself trapped

inside the alley, pressed against its dead-end wall. The hand lunged again, and

again, Jimmy desperately striving to avoid its lethal grasp, but then, tiring

and flustered, he stumbled, losing his balance. And as the terrified teenager

crouched, knowing all too well that he could not escape, the hand triumphantly hovered

over him, in an almost exultant stance, like a hooded venomous cobra of death about

to wield its fatal strike at last (see the panel opening the present ShukerNature

article that illustrates this dramatic, climactic scene).

Then, without warning, a deafening hail

of bullets shattered the stillness of the street, round after round after

round, from all manner of firearms, and all aimed directly at different portions

of the monster's gigantic serpentine length. Its murderous fingers stiffened,

and then its entire hand collapsed near to where Jimmy was slumped, prone with

fear. Whatever it had been, the Monster of Dread End was no more. Its hand lay

palm-upwards on the ground inside the alley, and crimson rivers of blood gushed

forth from its arm, which had been blown apart, broken up into several discrete

portions by the intensity of the barrage of artillery brought to bear against

it.

A number of figures now stepped out of

the shadows and deserted buildings where they had previously been in hiding,

including uniformed policemen, bazooka-toting soldiers, and plainclothes officials. One went over to the

hand and began examining its palm, noting that it contained pores through which

the creature had evidently absorbed the blood and other body fluids obtained

from its victims after its hand had crushed them.

The police apologized to Jimmy for not

having appeared on the scene earlier, explaining that they had always been here

and knew all about the monster, hoping that somehow, some day, they would

destroy it, but needing to wait until enough of the arm had emerged to ensure

their success in killing it when firing upon it, as opposed to merely wounding

it. However, it had always retreated back inside the manhole cover at the

slightest indication of danger. So when they spotted it pursuing Jimmy, they had

poised themselves in readiness, and once a considerable length of its arm had

emerged, they saw and took their best-ever chance of ending for all time the

monster's reign of terror, and which now, at last, was indeed over.

The

victorious concluding panel from the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The Monster of

Dread End' written by John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that first

appeared in Ghost Stories, #1,

September/October 1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced

here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review

purposes only)

Although

I hope that you've enjoyed my verbal retelling of 'The Monster of Dread End',

nothing can compare to the original illustrated, scripted comic-strip version.

So please click here to

view (and also, if you so choose, download) this entire 10-page, 44-panel comic-strip story.

As I noted when introducing the present

ShukerNature blog article, this comic-strip story may well have helped to

incite my cryptozoological curiosity, because even though its own monster was

so outrageously bizarre and grotesque, it probably played its part alongside a

host of other influencing factors in encouraging my mind to consider whether remarkable

creatures still unknown to science might actually exist. True, they were highly

unlikely to be anything even remotely as incongruous as this macabre entity,

but with Nessie frequently hitting the news headlines at that time, not to

mention the Patterson-Gimlin bigfoot film and yeti reports, I was becoming

increasingly aware that mystery animals may indeed exist. As a result, and

despite knowing full well that it was entirely fictitious, even as a youngster I

enjoyed hypothesizing how such a creature as the Monster of Dread End could arise.

Needless to say, I swiftly dismissed any

conjecture that the hand and arm may constitute just one limb of a truly

colossal sewer-dwelling mega-monster sporting other limbs as well as a head, neck,

torso, and possibly even a tail too, because such a veritable mountain of living

flesh existing inside the region's sewers would readily block them for miles

around in every direction, rapidly causing floods, road upheavals, and all

manner of other dramatic indications of its subterranean presence. In addition,

unless it had countless arms with body fluid-absorbing hands emerging from

manholes the length and breadth of the region concealing this underground

horror (a phenomenon that in itself couldn’t help but be noticed pretty darn

quickly, let alone the huge body count of victims soon arising from such

widespread predation), it assuredly could not sustain such a vast bulk if it

relied entirely upon just one single hand to obtain all of its necessary

nutrients.

Therefore, I reasoned, the ultra-flexible

arm must itself be the monster's body, an immensely long one, but a body

nevertheless – not so much a sewer alligator, therefore, as a sewer super-snake

or snake-like reptilian entity. But what about the hand? Either the creature kept its head hidden deep in the

bowels of the sewers and hunted by means of a highly-modified tail whose

terminal portion had evolved into a grasping, absorbing analogue of a

pentadactyl hand, which seemed totally ludicrous; or, admittedly only slightly

less so, the hand was actually the creature's highly-modified head instead,

again having evolved into a grasping, absorbing analogue of a pentadactyl hand.

Speculative evolution is an engrossing

subject in its own right. So even though it would struggle, I feel, to tender a

plausible scenario for the morphological development of anything recalling Dread

End's dreadful devourer, once again this latter comic-strip creation assisted

in directing my attention and cogitations towards that field of analysis too. In

short, 'The Monster of Dread End' story was influential in nurturing my early

interests in both cryptozoology and speculative evolution.

Front

cover of Ghost Stories, #1,

September/October 1962, published by Dell Comics (© Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

But what is the story of this story? That

is to say, who created it, where did it originate, and what else, if anything,

is known about it? This is what I was investigating early this morning, and I

succeeded in uncovering some fascinating facts. It turns out that 'The Monster

of Dread End' was the brainchild of a famous American comic book writer and

cartoonist named John Stanley (1914-1993), whose foremost claim to fame was

that he scripted (and also drew many of) the much-loved, exceedingly popular Little Lulu children's comic books from

1945 to 1959. However, in 1962 (not 1968, as sometimes incorrectly claimed), Stanley's creativity was channeled down a very different,

much darker direction when he wrote all four comic-strip stories in the very

first issue (September/October 1962) of a brand-new comic book published by

Dell Comics and entitled Ghost Stories

(which ran for 37 issues, folding in 1973). As this comic book's specific genre

was horror/suspense, Stanley's quartet of stories were aimed at a much more

mature readership than his previous work, their subjects all directly linked to

the supernatural or unexplained mysteries, and one of these stories was none

other than 'The Monster of Dread End', which was vibrantly illustrated by Ed

Robbins. The other three were 'The Black Stallion' (no relation whatsoever to

the same-named series of children's novels by Walter Farley; click here

to view it), 'The Werewolf Wasp' (click here

to view it), and 'The Door' (click here

to view it).

Prior to this morning, I had always assumed that 'The Monster of Dread End' was merely some obscure, historically unimportant comic-strip story that had been created specifically for some equally insignificant late 1960s/early 1970s annual-type comic book (i.e. the one that I had owned a copy of as a child). Hence I was very startled to discover when researching this selfsame story today not only that it had actually first appeared in the Sept/Oct 1962 debut issue of of Ghost Stories, but also that almost 60 years after its original

publication, this latter issue is still popularly claimed (and has even been voted) by comic book devotees to be

the scariest single comic-book issue ever published, and 'The Monster of Dread

End' the scariest single comic-strip story ever published (little wonder why I found it so

unnerving, albeit fascinating, as a child!).

Indeed, both this issue and this

particular story within it have attained legendary status in such circles, to

the extent that there is even a Spanish stop-motion mini-movie based upon the Dread

End monster (which I'd love to see but haven't been able to locate anywhere

online so far – suggestions?), as well as Horror Show Mickey's expanded, 15.5-minute

retelling of its story currently on YouTube (click here

to view this, which features much of the original comic-strip visuals, although

some of its panels have been re-ordered in order to fit the story's reworking

by HSM). In 2017, a Kickstarter project was launched by Emmy-award-winning visual effects artist and publisher Ernest Farino whose aim was to fund the production of a professional trailer that could then be utilised in pitching for the production of a stop-motion feature-length movie based upon this iconic story, but sadly it did not reach its targeted goal (click here for further information). Given the sensational CGI capabilities now available to film producers, however, perhaps this latter technology may offer a more viable alternative way forward in creating what could be a truly spectacular full-length Monster of Dread End movie. Additionally, in February 2004, artist Peter Von Sholly created an updated, photo-montage version of the classic original Stanley/Robbins comic-strip story. Simply entitled 'Dread End', it contains several notable changes made by Sholly – for instance, Jimmy is now named Stanley (in homage to John Stanley), the "balled-up things" are depicted (not for the squeamish!), and Jimmy's/Stanley's police whistle has been replaced by a mobile phone (click here and here for more details concerning Sholly's adaptation).

I have also ascertained that the

still-unidentified annual-type comic book that I owned as a child in which 'The

Monster of Dread End' appeared was evidently a compilation of comic-strip

stories from a number of different issues of Ghost Stories, because when I checked down lists, titles, plot details,

and images from those original issues I found other stories that I can remember

from that annual. These latter include 'Blood, Sweat and Fear' and 'When Would

Death Come For Daniel DuPrey?' (both of which originally appeared in Ghost Stories #3), written by Carl

Memling and illustrated by Gerald McCann.

All that I need to do now, therefore, is

discover the identity of this elusive volume. And so until/if ever I do, I

shall continue to search for it online and anywhere else that I can, as and when

the mood takes me. Call it a work in progress. Obviously, however, if anyone

reading this article can offer me any suggestions, information, or assistance

relating to my ongoing quest, I would be truly grateful. Who knows – if I do find

out what it is, I might even then seek out a copy to purchase and reacquaint myself

with its spine-chilling contents. Then again, in view of how they haunted my

nights, albeit so very long ago now, might it be best to let sleeping dogs, and

absent annuals, lie?

Revealed

at last! A panel from

the legendary comic-strip horror story 'The Monster of Dread End' written by

John Stanley and illustrated by Ed Robbins that first appeared in Ghost Stories, #1, September/October

1962, published by Dell Comics (© John Stanley/Ed Robbins/Ghost Stories/Dell Comics – reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

UPDATE #1: 4 May 2021

It looks as though I've finally identified the mysterious annual-type comic book that I owned as a child and which included among its creepy, chilling comic-strip stories 'The Monster of Dread End'. From what I've been able to uncover, it was a one-off publication entitled Ghost Stories: Television Picture Story Book, which was published in (or around) 1970 by World Distributors, a leading publisher of annuals in the UK. Not only does its main title directly tie in with that of the original Ghost Stories comic book issues, which were still being published at that time, but in addition its front cover illustration is actually identical to that of Ghost Stories #3. Moreover, its 1970-ish date of publication matches the time when I owned the book. Obviously I need to examine a copy of this publication directly, or at least see a complete listing of its contents, in order to be absolutely certain, but I think it very likely that this is indeed the book that I've been searching for.

Ghost Stories: Television Picture Story Book (© Ghost Stories/Dell Comics/World Distributors – reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

UPDATES #2 & #3:

5 & 6 May 2021

My recent success at identifying the

above annual-type comic book as the book that I'd once owned as a child around

50 years ago, containing John Stanley's seminal 'The Monster of Dread End' cryptozoology-themed

comic-strip story, has in turn inspired me to make renewed attempts (the latest

of many) at seeking out two other longstandingly elusive comic-strip stories

that I remember so well reading as a child but have never been able to identify

or trace since then. So during these past two days this is precisely what I

have done, and, amazingly, both searches have again been successful, at long last.

Consequently, although neither of these latter two comic-strip story's subject

is of cryptozoological relevance, it feels fitting to include details of them

here, as their own reappearances in my life are due directly to my having been

inspired to uncover them by having rediscovered 'The Monster of Dread End'. So

here they are:

THE 10,000

DISASTERS OF DORT

Another success duly chalked up in my ongoing "All My

Yesterdays" rediscovered memories. This one concerned a comic-strip story

that I'd read in some UK boys' comic back in the early 1970s. It was all about

the planned invasion of Earth by an advanced alien civilisation due to the

impending death of their own planet or sun. But first they had to clear Earth

of humanity, so chose to do this by inflicting a massive number of calamities

upon us, and which looked as if they were going to succeed until, unexpectedly,

the aliens discovered that they had a fatal weakness – our planet's microbes

proved lethal to them (H.G. Wells's classic novel The War of the Worlds comes readily to mind here!). I knew that

this comic-strip story's title referred to the number of calamities, and that

the number was high, but that's all that I could remember re that aspect. As

for the comic in which this story appeared: I had in mind Thunder, which I used to have each week, but which finally merged

with another boys' comic. Yet when I checked online, I could not find any

indication of this story within any of Thunder's

issues. Ditto when I tried various other comics that I used to have at that

time, including Lion, the boys' comic

that Thunder had merged with.

But tonight, 5 May 2021, I finally achieved success, when I discovered

that in May 1974, what was then Lion and

Thunder merged with yet another UK boys' comic, Valiant, to become Valiant

and Lion - and it was in the last few issues of Lion and Thunder before merging with Valiant that the sought-after comic-strip story had appeared. And

its title? 'The 10,000 Disasters of Dort' (Dort being the aliens' home planet).

It was written by Mike Butterworth and illustrated by Studio Bermejo. I've now

found a few sample pages featuring panels from that story, and even an issue of

Lion and Thunder in which it appears

in full colour on the front page. Moreover, I've learnt that this story had

actually appeared previously, in Lion,

this original run spanning 18 May to 23 November 1968, in which it had a

different ending. However, the Wellsian one had replaced it when reprinted in Lion and Thunder, from 22 December 1973

to 4 May 1974, in order to bring the story to an end in time for the comic's

merger with Valiant. It would be

interesting to know what its original ending had been.

Select pages from instalments of 'The 10,000 Disasters of Dort' in Lion and Thunder, including (far right)

the concluding panels depicting its Wellsian ending there (© Lion and Thunder/IPC/Freeway

Publications – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

PROPHET OF DOOM

I'm on a roll with my

"All My Yesterdays" project - yet another longstanding mystery

comic-strip story duly rediscovered. During the late 1960s/early 1970s, I read

a comic-strip story in some UK comic annual about a villainous man from the

distant future who arrives in our time with a plan to take over the world as

its absolute ruler by holding over each major power the threat of destruction

via his superior technological knowledge unless a huge sum is paid. But when he

jauntily arrives at the office of some major international governmental figure

to present his demands, he is shocked to discover that this figure is also from

the distant future, and is in fact one of many from there who are here

specifically to trap future villains like him. The one odd thing about it that

I can particularly remember is that the two future men both had antennae! I

also remember another comic-strip story from the same comic annual, all about a

space villain named Disastro.

This unusual name provided me

me a distinctive clue that I was able to use in tracing the mystery annual,

which, as I discovered today, 6 May 2021, turned out to be the 1969 annual for

the UK boys' comic Fantastic,

containing a comic-strip story featuring the UK super-hero Johnny Future

battling the villainous Disastro. But that was not all. It also contained

another comic-strip story called 'Prophet of Doom', written by the celebrated

Stan Lee and illustrated by Steve Ditko, which had been reprinted from issue

#40 of the Marvel comic book Tales of

Suspense, which had been published in 1963. And when I checked up the plot

of that story, it was a perfect match to my memory of the antenna-sporting

villain from the future and his similarly-sporting and originating nemesis. The

final clincher was a series of illustrations from this story, which I'm

presenting here. So I must have owned Fantastic

Annual 1969 at some point (I know that I owned its annual from the

following year, because I still do), yet its front cover picture rings no bells

in my memory. Never mind, at least I've solved yet another riddle from my

comic-reading childhood.

Front

cover of Fantastic Annual 1969 and a

selection of panels depicting the villainous future man from 'Prophet of Doom'

(© Fantastic/Odhams Press/Stan

Lee/Steve Ditko/Tales of Suspense/Marvel

Comics/ – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

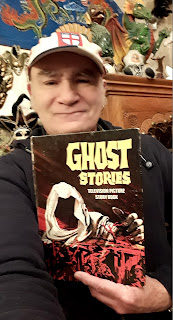

UPDATE #4: 8 November 2022

Rejoice! I finally obtained a long sought-after childhood memory in book form at today's home-town bric-a-brac market, but not from the market itself this time. I regularly meet up there with a longstanding friend, Tim, who shares many of my interests, such as cryptozoology and the unexplained, sci fi/fantasy movies and novels, comic-book super-heroes, etc. A couple of weeks ago, I casually mentioned to him there about my seemingly never-ending quest for a book that I'd owned as a youngster but had eventually given away and had always regretted it afterwards, especially as I'd never succeeded in purchasing another copy of it anywhere. It was of course the above-documented Ghost Stories hardback annual-type comic-strip book from 1970. To my amazement, Tim just as casually mentioned that he owned a copy of it and that along with a fair few others from his collection he was planning to list it for sale on ebay! Needless to say, I begged for first refusal on it, so he said he'd bring it along to the next market. Circumstances beyond our control arose to delay this, however, but today when we met up, Tim had indeed brought it with him and sold it to me for half of what he'd intended to list it for. I said I'd be more than happy to pay him what would have been his full listing price for it, but he wouldn't hear of it and was pleased that he'd been able to help me succeed in my quest for this elusive book.

So here it is, AT LAST, another long-missing piece from the time-dispersed jigsaw puzzle of my youth restored into its long-vacant place. Back home this afternoon, I read through the entire book at a single sitting, recalling how its stories had chilled my spine half a century ago, but now were merely whimsical curiosities, albeit still well-remembered ones. The highly-impressionable, exceedingly imaginative youngster I'd been when I'd originally read them is now a world-weary, hopefully (but by no means definitely) wiser oldie who realises only too well that the world contains far more terrifying realities than anything that can ever be found in any comic-book, but all the same I am very glad to have this one again. Thanks Tim!

Holding my newly-purchased copy of the long-sought-after Ghost Stories: Television Picture Story Book (© Dr Karl Shuker)