Is

this a bilby I see before me – in Peru?? (public domain)

In my previous ShukerNature blog article

(click here

to access it), I documented two unexpected creatures depicted in a magnificent

mural-format pictorial encyclopaedia entitled Quadro de Historia Natural, Civil y Geografica del Reyno del Peru

('Painting of the Natural, Civil and Geographical History of the Kingdom of

Peru'), or QHNCGRP for convenience hereafter

in this present article. Consisting of numerous miniature oil paintings and

accompanying text on a wood panel, it measures a very impressive 128

x 45.25 inches (325 x 115 cm).

Completed in Madrid, Spain, in 1799 and

now on display at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Madrid (Spain's

national museum of natural history), which has produced an exquisite, lavishly-illustrated website devoted specifically

to it (click here),

QHNCGRP was authored by Basque-born

but (for three decades) Peru-based scholar José Ignacio Lequanda, who

commissioned French artist Louis Thiébaut to produce the 194 paintings

illustrating it. As noted above, most of these are miniatures, with tiny but

voluminous text by Lequanda accompanying all of the 160 miniatures depicting

fauna and flora of Peru or its South American environs.

The vast majority of these miniatures

depict readily-recognisable Neotropical species, including a large spotted

rodent named the paca, a South American zorro or 'fox' (actually a species of Dusicyon canid), an otter, tapir,

manatee, various monkeys, trumpeter bird, cock of the rock, spoonbill,

hummingbird, Humboldt's penguin, skunk, caiman, giant anteater, fulgorid lantern-fly,

llama, vicuna, armadillos, coati, and opossum, to mention but a few.

View

of QHNCGRP in its entirety – click to

enlarge for viewing purposes (© Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales –

reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

Also present, however, are certain

decidedly mystifying zoological portraits, such as that of a dramatically

out-of-place Madagascan black-and-white ruffed lemur and one of a putative

living ground sloth, both of which I documented in my previous QHNCGRP article.

Since writing that, I have been paying

further close attention to this marvelous pictorial menagerie, and I've spotted

several additional examples included within it that are nothing if not curious

or controversial, for various differing but equally interesting reasons. So

here they are – make of them what you will!

Take, for instance, the very distinctive

creature portrayed in the QHNCGRP

miniature that opens this present ShukerNature article. Whereas I am not aware

of any South American mammal matching its morphology (Lequanda claimed it to be a vizcacha, and others have suggested the latter rodent's relative the chinchilla, but these bear little – in the case of the chinchilla – or no – in the case of the vizcacha – resemblance to it, I am aware that it does bear

a remarkable similarity to a certain species of exclusively Australian

marsupial. Namely, the lesser bilby (aka lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot) Macrotis leucura.

Mystery

big-eared, long-snouted, plume-tailed QHNCGRP

mammal (above) and a painting of a lesser bilby from English zoologist Oldfield

Thomas's Catalogue of the Monotremes and

Marsupials in the British Museum (Natural History) (below) (public domain)

Certainly, its long snout, lengthy plumed

tail, and very sizeable ears all correspond very closely to those of the latter

species. True, its forelimbs are much the same size as its hind ones, whereas

those of the lesser bilby are shorter, and its fur is white rather than brown

like the bilby's. However, the limb discrepancy may simply be an error on

Thiébaut's part, especially if his subject's preserved skin had become

distorted via shrinkage. Moreover, preserved skins frequently blanch if exposed

too long to light (the taxiderm thylacine that was on public display in

London's Natural History Museum when I visited in 2014, for example, was so

faded, predominantly cream in colour all over, that its diagnostic stripes had

vanished).

Deriving its English name from its very

large, slender, rabbit-like ears, and characterized by its tail's long white

hairy plume, the lesser bilby was once native to the deserts of central

Australia, but has not been conclusively sighted since the 1950s, so is now

deemed extinct. Back when QHNCGRP was

created, however, it was still in existence, with preserved specimens in

museums.

As apparently happened with the ruffed

lemur, is it possible, therefore, that Lequanda and/or Thiébaut saw a museum specimen

of the lesser bilby at Madrid's celebrated Royal Natural History Cabinet

(founded in 1771, opened to the public in 1776, and whose contents were very

familiar to Lequanda), or even elsewhere, and mistakenly assumed that it was a

Neotropical species? Or might Thiébaut have based his miniature upon some

pre-existing artwork by another artist? There is a notable QHNCGRP–linked precedent for this latter possibility.

Thiébaut's

zebra-striped QHNCGRP mystery monkey

(top left), Compañon's earlier artwork upon which Thiébaut's was based (top right),

and a South American tree porcupine (below) (public domain / public domain / (©

Eric Kilby/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

One of the several monkeys depicted as

miniatures in QHNCGRP by Thiébaut is

the extraordinary-looking striped example shown above. Its bold zebra-like body

and limb markings instantly set it apart from any currently-known monkey

species, as does the mid-dorsal row of spines running down its back. These are

also alluded to by Lequanda, in his accompanying text. He referred to this fascinating

fasciated creature as a casacuillo, and also mentioned that it lived upon fruit.

Rather than basing his illustration of this

casacuillo upon first-hand observations of a living or preserved animal,

however, Thiébaut used as his inspiration a pre-existing 18th-Century

illustration. Namely, a water-colour prepared some years earlier with 1,410

others for inclusion in the Codex Martínez

Compañon, a sumptuous nine-volume manuscript made by Baltasar Jaime Martínez

Compañon, Bishop of Trujillo, Peru. This water-colour is also shown here, for

comparison purposes alongside Thiébaut's oil painting.

Moreover, according to writer Carmen

Martínez, writing in an online article from June 2021 devoted to QHNCGRP (click here

to access it), this creature is not a monkey at all, but is instead a South

American tree porcupine or coendou, of which there are many species, all

sporting a prehensile tail. However, to me it looks no more like a tree porcupine

than it does a monkey! Coendous are not striped and their fine spines are

present profusely over their entire body, not merely along their back. So I am

unconvinced by this identification.

A

striped carrot on legs!! Another of Triébaut's bemusing mystery beasts included

by him in QHNCGRP (public domain)

And speaking of zebra-patterned mystery

beasts depicted in QHNCGRP, what are

we to make of the example shown above? It looks for all the world like a striped

carrot on legs! It seems to be furry, eared, and whiskered, and is included in the left-hand block of 30

mammal miniatures (according to Lequanda, moreover, it is, once again, a coendou!), so we must assume that it is indeed mammalian – or should

we?

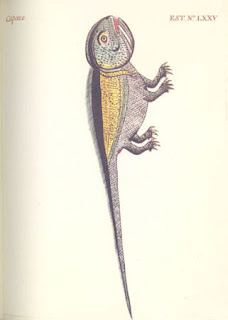

After all, also included in this same

block of miniatures is the following bizarre beast, popularly if improbably(?)

deemed to be a portrait of an iguana according to various sources consulted by

me

Yet this latter beast is itself a major

mystery. For it seems to possess a stiff pointed tail wholly unlike the highly

flexible tail of an iguana, as well as long curved fangs emerging from its

jaws, and what looks like a pair of wings pressed tightly against its flanks! Apparently, like the striped monkey/coendou illustration, Thiébaut based his miniature upon one from the Codex Martínez

Compañon that was labelled as an iguana. Really??

A

supposed iguana depiction by Thiébaut in QHNCGRP

(above) and the original version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

Most improbable of all, however, must

surely be the next example presented here. What on earth (or in the air!) is

this extraordinary squirrel-like entity that sports not only two pairs of limbs

and a bushy tail but also a pair of wings – and which are clearly functional,

given that Thiébaut has portrayed it flying above a somewhat larger, rodent-like

mammal in the same miniature?

Might it be the inaccurate result of

Thiébaut painting not from direct observation of some physical specimen, but

instead merely from a verbal description of a flying squirrel? True, the name of

these rodents is something of a misnomer, seeing that they become airborne not

with the assistance of wings but instead via a pair of gliding membranes (patagia),

linking their wrist and ankle on each side of their body. But if a verbal

description of such a creature does not make this distinction clear to an

artist seeking to depict it, the result might well be an illustration of a

squirrel-like creature boasting a pair of bona fide wings.

Yet even if that were true, there is still

a fundamental problem in applying it as an explanation for this aerial anomaly as

portrayed here, because although flying squirrels are widely distributed in

North America, they do not occur anywhere in South America. So why would

Thiébaut have depicted one in QHNCGRP?

Yet another instance of someone wrongly assuming that a given creature is

Neotropical when it definitely is not? Having said that, Thiébaut's illustration is yet again a copy of one from the Codex Martínez

Compañon, but in that version the flying entity looks far more like a bird than a mammal, so why did Thiébaut convert it into one in his copied version? Conversely, at least according to Lequanda's accompanying description of it in QHNCGRP, it is indeed a rodent with wings, and is referred to by him as a mutmut. All very strange!

Thiébaut's

bewildering winged squirrel in QHNCGRP

(above) and the original bird-like version in the Codex (below) (public domain)

My concern with the ostensibly

unidentifiable mystery creatures from QHNCGRP

documented by me here is that, as already noted, most of the animals depicted

in it by Thiébaut are readily recognisable. So as those were all accurately

represented by him, why should the mystery beasts here not be too, unless he was indulging in some sly humour at Lequanda's expense, perhaps? Yet if they are accurate representations, why can we

not identify them?

Might at least some of them not have

arisen through misapprehensions regarding the origins of specimens utilized as

subjects, or even as a result of poor verbal descriptions of such, but instead

be bona fide native Neotropical species that have become extinct before ever

becoming known to European scientists, so their morphological appearance is

wholly unfamiliar to us?

The last anomalous animal to be

considered here may provide key evidence that some of Thiébaut's miniatures

depict significant creatures that were still unknown to science at the time

when he depicted them.

The

supposed lowland tapir depicted in QHNCGRP

(public domain).

Just a few hours after I posted my

previous QHNCGRP-themed ShukerNature

article, on 22 December 2022, I received a very interesting, thought-provoking

comment from a reader with the Google username Andrew, and which I duly posted

beneath my article. It concerns the QHNCGRP

miniature of what is officially assumed to be a specimen of the lowland (Brazilian)

tapir Tapirus terrestris, the largest

species of native mammal known to be alive today in South America, and

occurring widely here, including in Peru. Here is Andrew's comment:

Thiébaut's depiction of the

tapir looks like it could have been based on descriptions of the

then-undiscovered mountain tapir, rather than the lowland species. It has no

crest, its coat is almost black with a slight chestnut tint, and it seems to have

white lips.

Smaller and darker in colour than the

lowland tapir, the mountain tapir T.

pinchaque is a very distinctive species that is indeed uncrested and

white-lipped. It is also noticeably woolly, and looking at the tapir miniature in

close-up its body surface does appear to be hairy. Moreover, of particular

historical note is that this species, which is indeed native to Peru (occurring

in its far north's montane cloud forests), was not formally described by

science until 1829 – 30 years after the creation of QHNCGRP.

A lowland

tapir (top) and a mountain tapir (bottom) (© Dr Karl Shuker / (© Richard

Sifry/Wikipedia – CC BY 2.0 licence)

In short, if the tapir miniature in QHNCGRP actually depicts a mountain

tapir rather than a lowland tapir, this means that Thiébaut had portrayed a

major mammalian species three decades before its official discovery. This in turn begs the question: what specimen

was utilized by Thiébaut as the subject for his illustration?

Whichever it was, and wherever it was,

its taxonomic significance as representing a dramatic new species had clearly

not been recognized or appreciated by scientists of the day.

As I have revealed many times in my trio

of books on new and rediscovered animals, this is a sad situation that has occurred

countless times down through the centuries, with obscure museum specimens having

been long overlooked before belatedly receiving serious attention, only for

them then to be revealed as extraordinary new species whose existence had never

previously even been suspected, let alone confirmed. So the potential example

documented above has plenty of precedents, that's for certain!

My

three books on new and rediscovered animals (© Dr Karl

Shuker/HarperCollins/Stratus Publishing/Coachwhip Publications)