'Antlered elephants' and other North

American prehistoric fauna from the Eocene epoch in what is today Wyoming, USA,

as depicted in William D. Gunning's book Life History of Our Planet (1881)

(public domain)

Have there ever been antlered elephants? Not as far

as we know – so how can the extraordinary illustration presented above be

explained? The answer dates back to the intense rivalry between two eminent

American fossil collectors, resulting in the so-called Bone Wars that

galvanised 19th-Century palaeontology, and focuses upon the subject

of one of their most fervent bouts of competitive taxonomic classification – a

long-extinct but spectacularly strange-looking group of huge ungulate mammals

known as uintatheres.

Uintatheres have always held a special place in my

childhood memories because the very first artistic reconstruction of a fossil

mammal's likely appearance in life that I ever saw was of a Uintatherium

– vibrantly depicted on one of the opening pages of my How and Why Wonder

Book of Wild Animals (1962) that my mother bought for me when I was about 4

years old during the early 1960s. I read that poor, long-suffering book so many

times and with such youthful enthusiasm that it eventually fell apart, but a

replacement copy was soon purchased, which I still own today, so here is that

wonderful, fondly-remembered illustration:

Uintatherium depicted by Walter Ferguson in The

How and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (© Walter Ferguson/Transworld Publishers / inclusion here strictly on Fair Use/non-commercial basis only)

But what are – or were – uintatheres?

Named after the mountainous Uinta region of Wyoming and Utah where their first scientifically-recorded fossils

were uncovered, they belonged to the taxonomic order Dinocerata ('terrible

horns'). This was an early group of extremely large, superficially

rhinoceros-like ungulates (but possessing claws rather than hooves), which

existed from the late Palaeocene to the mid-Eocene, approximately 45 million

years ago. The males of its most famous, culminating members, the uintatheres (which

existed during the mid-Eocene), bore no less than three separate pairs of blunt

ossicone-like horns on their heads. These consisted of a rear pair arising from

the parietal bones near the back of the skull, a middle pair arising from the

maxillae or upper jaw bones, and a front pair arising from the nasal bones. Their

function remains uncertain, but they may have been used for defence and/or for

sexual display purposes. Also, their skull was very concave and flat in shape, and

with very thick walls, thus yielding so restricted a cranial cavity that the

brain was surprisingly small for such sizeable animals.

Today, two major genera of uintatheres are recognised

– Uintatherium and Eobasileus (plus a few less well known ones,

such as Tetheopsis) – which are very similar to one another

morphologically, and are distinguished predominantly by way of certain

differences in skull proportions, as delineated in the following diagram and

table. These originate from the definitive work on uintathere taxonomy, North Carolina University palaeontologist Dr Walter H. Wheeler's comprehensive paper 'Revision

of the Uintatheres', published in 1961 as Bulletin #14 of the Peabody Museum of

Natural History, Yale University.

Also, whereas the skull of Uintatherium was

relatively broad, with the parietal bones positioned some way in front of the

occiput (the skull's rearmost portion), in Eobasileus the skull was long

and narrow, with the parietal horns further back and therefore much closer to

the occiput.

In addition to their horns, male uintatheres also

possessed a very sizeable pair of downward-curving upper tusks (they were much

smaller in females), protected like scimitars by bony scabbard-resembling lower

jaw down-growths. Behind each of these two tusks was a noticeable gap

(diastema), separating the tusk on each side of the upper jaw from that side's

first premolars. In Uintatherium, the maxillary horns were positioned

directly above the diastema in each side of the upper jaw, whereas in Eobasileus

they were positioned further back, above the premolars.

Comparing the structure of a Uintatherium

anceps skull at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France

(above) with that of an Eobasileus cornutus skull at the Chicago Field

Museum (below) (public domain / © Dallas Krentzel/Wikipedia)

Uintatherium was a massive browsing ungulate, up to around 13 ft long, 5.5 ft tall, and up to 2 tons in weight. Only two species

of Uintatherium are recognised today – North America's U. anceps (the most famous dinoceratan of

all, formally named and described in 1872 by American palaeontologist Prof. Joseph

Leidy), and China's more recently-recognised U. insperatus (named and

described in 1981).

Only one Eobasileus species is nowadays

recognised – E. cornutus, named by fellow American palaeontologist Prof.

Edward Drinker Cope in 1872. This was the largest uintathere of all, and in

fact the largest land mammal of any kind during its time on Earth, with a total

length of around 13 ft, standing 6.75 ft high at the shoulder, and weighing up to 4.5 tons.

Just over a century ago, however, a bewildering

plethora of uintathere genera and species had been distinguished and named, due

not so much to any taxonomic merit, however, but rather to the driven desire by

two implacable fossil-collecting foes during the 1870s and 1880s to outdo one

another in their febrile quest for palaeontological immortality and to destroy

each other's scientific reputation, until their obsession eventually ruined

both of them, socially and financially.

Their names? Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899), and

Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897).

After having been professor of vertebrate

palaeontology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Marsh became the first curator at the Peabody

Museum of Natural History at Yale University (the museum having been founded by his wealthy uncle, the philanthropist

George Peabody). Conversely, Cope preferred field work to academic research, as

a result of which he never held a major scientific post of any lengthy tenure,

though he did become professor of zoology for a time at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, his home city.

Although they are most famous for their frenzied

attempts to best one another in the description of new dinosaur species, Marsh and

Cope also constantly challenged each another along similar lines in relation to

their descriptions of new uintatheres. The regrettable, chaotic result was the

creation not only of numerous new species but also of many new genera, several

of which were named within the space of a single year, and all of which were unjustified,

having been founded upon the most trivial, taxonomically insignificant of

differences.

This sorry, farcical state of affairs is preserved today in the startling array of junior synonyms attached to the genus Uintatherium, including the nowadays long-nullified genera Dinoceras (coined by Marsh in 1872), Ditetrodon (Cope, 1885), Elachoceras (Scott, 1886), Loxolophodon (Cope, 1872), Octotomus (Cope, 1885), Tinoceras (Marsh, 1872), and Uintamastix (Leidy, 1872). Although I normally have little interest in abandoned names, I do feel a pang of regret for the loss of one particular example here – the wonderfully-named Dinoceras mirabile (synonymised with Uintatherium anceps), which was coined in 1872 by Marsh, and translates as 'marvellous terrible-horn' – a very evocative, accurate description of how this extraordinary beast would have looked in life.

This sorry, farcical state of affairs is preserved today in the startling array of junior synonyms attached to the genus Uintatherium, including the nowadays long-nullified genera Dinoceras (coined by Marsh in 1872), Ditetrodon (Cope, 1885), Elachoceras (Scott, 1886), Loxolophodon (Cope, 1872), Octotomus (Cope, 1885), Tinoceras (Marsh, 1872), and Uintamastix (Leidy, 1872). Although I normally have little interest in abandoned names, I do feel a pang of regret for the loss of one particular example here – the wonderfully-named Dinoceras mirabile (synonymised with Uintatherium anceps), which was coined in 1872 by Marsh, and translates as 'marvellous terrible-horn' – a very evocative, accurate description of how this extraordinary beast would have looked in life.

Uintatherium as portrayed upon a postage stamp

issued by Afghanistan in 1988, from my personal collection (© Afghanistan

postal service / inclusion here strictly on Fair Use/non-commercial basis only)

But what has all (or any) of this to do with

antlered elephants? I'm glad you asked! Because uintatheres were indeed so astounding

in form, when their first fossils were discovered palaeontologists were by no

means certain which creatures were their closest relatives, and how, therefore,

they should be classified. Cope, who was particularly enthralled by them, was

convinced that such huge ungulates must surely be related to elephants, and he even

opined that they probably possessed a long nasal trunk like elephants plus a

pair of very large, wide, elephantine ears, and that they should be housed with

them in the taxonomic order Proboscidea, thereby conflicting yet again with Marsh's

view (in 1872, Marsh had placed them within their very own order, Dinocerata). But

that was not all.

Cope also speculated that their rearmost, parietal pair

of horns may have been much larger than the other two pairs, possibly even

branched and covered in velvet, thereby resembling the antlers of deer. And so,

in various early reconstructions of their putative appearance in life, this is

exactly how uintatheres were portrayed – as antlered, large-eared,

trunk-wielding pachyderms, resembling the highly unlikely outcome of an equally

improbable liaison between an elephant and a moose!

Eobasileus cornutus with elephant ears and trunk , from

an August 1873 Pennsylvania Monthly article by Edward Drinker Cope (public domain)

True, there were certain less dramatic versions –

one illustration (see above) that appeared in a Pennsylvania Monthly

article from August 1873 by Cope concerning the uintathere species now called Eobasileus

cornutus portrayed it with tall unbranched parietal horns rather than with parietal

antlers (although they are still slightly palmate at their distal edges), but did

gift it with an elephant's ears and trunk (as instructed by Cope). However, the

two most (in)famous examples of this specific genre of reconstruction were

rather more extreme, and both of them appeared in William D. Gunning's book Life

History of Our Planet (1881). One of these is the following diagrammatic

reconstruction:

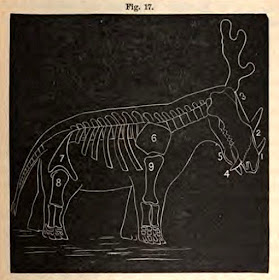

Line diagram of a Uintatherium

(spelt 'Uintahtherium' here) as an antlered elephant-like beast in Gunning's

book (public domain)

Gunning's comparisons drawn between this remarkable

creature and various modern-day animals were equally memorable, albeit

decidedly fanciful in parts (notably its small brain allying it with the

marsupials!):

"We are as astronomers taking the

parallax of a distant star. The animal which roamed along the banks of that Wyoming lake is as far from us in time as the

star in space. What is its parallax? what its place in the scheme of creation? The

long, narrow head with skull elevated behind into a great crest, the molar teeth

and arch of the cheek-bone are characters, which indicate relationship with the

Rhinoceros. The absence of teeth in the premaxillaries points to the Ruminants.

The vertical motion of the jaw points away from the Ruminants, towards the

Carnivores. The great expansion of the pelvis, the complete radius and ulna,

the shoulder-blade and the hind-foot, are characters which affiliate our animal

with the Elephant. The diminutive brain would place it with the pouched

Opossum.

"The horns on the maxillaries, the

concavity of the crown, and the enormous side crests of the cranium are

characters which remove the animal from all living types. We have found the

ruins of an animal composed of Elephant, Rhinoceros, Ruminant, Marsupial, and

a something unknown to the world of the living. Drawing an outline around the

skeleton, we have a long head with little horns on the nose, conical horns over

the eyes, and palmate horns over the ears, with pillar-like limbs supporting a

massive body nearly eight feet high in the withers and six in the rump.

Eliminating from its structure all that relates to the living, so many and such

dominant structures remain that we cannot choose for it a name from existing

orders. We will call it Uintahtherium

[sic], which means, the Beast of the Uintah Mountains."

A

pair of antlered elephantine uintatheres appeared in this same book's

frontispiece illustration, but this time fleshed out rather than in diagrammatic

form, as part of an Eocene panorama of North American mammals. The illustration

in question opens this present ShukerNature post, and is also reproduced below,

together with its original accompanying caption:

The frontispiece

illustration of Gunning's book, featuring a pair of antlered uintatheres

(public domain)

By the

end of the 19th Century, however, with many additional fossilised

remains having been discovered in the meantime, palaeontological views

regarding both the morphology and the taxonomy of the uintatheres had changed

markedly. Cope's views concerniing them had been totally rejected in favour of

Marsh's, thus promoting the belief still current today that these mammalian

behemoths represented a lost ungulate lineage, unrepresented by (and unrelated

to) any that are still alive in the modern world.

A rather

more modern-looking Uintatherium as illustrated in the Reverend H.N.

Hutchinson's book Extinct Monsters (1897)

So it

was, for instance, that Uintatherium was illustrated in Extinct

Monsters (1897) by the Reverend H.N. Hutchinson in much the same manner as

it still is now, over a century later, shorn of its velvet-surfaced antlers and

with only relatively short and blunt, unbranched horns in their stead, plus much

smaller ears, and a conspicuous lack of any probiscidean trunk. The antlered

elephant was no more – a most unlikely uintathere had soon become a non-existent fossil phantom blown swiftly away by a

brisk, incoming breeze bearing new discoveries and new ideas borne from a new

generation of researchers. 'Twas ever thus.

My How

and Why Wonder Book of Wild Animals (1962), containing the first Uintatherium

illustration that I ever saw as a child (© Transworld Publishers / inclusion here strictly on Fair Use/non-commercial basis only)

If Wyoming had palm trees, it could have had antlered elephants too :)

ReplyDeleteI miss the illustrations of mid to late 20th-century children's nature books. There's so much life and colour in them! The unnatural juxtapositions probably help. :)

ReplyDeleteThese days, I have to be careful not to be like those two scientists. In certain software matters, I find it awfully tempting to fight to win an argument rather than stick to facts.