What strange, secretive, and

sometimes even sinister creatures of cryptozoology – or even of something else

entirely – might still lurk undetected by science amid the shadowy depths of forbidding

forests in the remotest regions of West Africa? (Pixabay/free usage)

Ati, bwana! There is a story you will not believe,

because you are a white man. White men laugh at the stories told by the black

man. They say this is not so, and that is not so. We have not seen this or

that, so how can it be? They say, Ho, Ho! Black men are like little children,

telling tales to each other in the dark. But remember, bwana, white men have

been in this country for a time that is less than the life of one man, so how

can you know all the things that have been known to black men for a hundred

lifetimes and more?

Roger

Courtney – A Greenhorn in Africa, quoting an elderly African

hunter, Ali

Whereas many

mystery animals have been well documented from North, East, Central, and

southern Africa, far fewer have been publicised from West Africa - especially

from its westernmost corner, constituting The Gambia and its encompassing neighbour,

Senegal. Yet these two small countries (sometimes referred to collectively as Senegambia) apparently

harbour a sizeable array of bizarre, unidentified beasts rarely if ever brought

to widespread cryptozoological attention...until now.

Owen Burnham in Kenya's

Namanga Hills Forest

(© Owen Burnham – photograph kindly made available to me by Owen for use in relation

to my cryptozoological writings)

I owe a great

debt of thanks to a longstanding colleague, naturalist Owen Burnham, who spent

his childhood and teenage years in Senegal, for very

kindly supplying me during our longstanding correspondence with information

regarding the creatures documented here. While living in Senegal, Owen became

formally accepted as an honorary member of the native Mandingo (Mandinka)

tribe, and thus learnt much about this land's mystery animals and also those of

Gambia that has

remained unknown to other Westerners.

One such

creature, the Gambian sea serpent, or Gambo for short, launched my own career

in cryptozoology when I investigated its case in detail during the mid-1980s,

and has now become very well known and well-documented in the literature (click

here to access my extensive coverage of

this cryptid on ShukerNature). However, Owen also learnt of several other

mystery beasts that have received far less publicity, and so it is with these

hitherto little-documented yet no less interesting examples that this present

ShukerNature blog article is concerned.

Illustration

of Gambo produced by Mark North for publicity material appertaining to the

Centre for Fortean Zoology's 2006 Gambian expedition (© Mark North/CFZ)

MYSTERY STONE

PARTRIDGE

This enigmatic

Senegalese bird was originally documented by me in a World Pheasant

Association News article (May 1991) on gallinaceous mystery birds.

The stone

partridge is represented in Senegal by its nominate

subspecies Ptilopachus petrosus petrosus – a familiar sight to Owen.

However, he remains perplexed in relation to the covey of stone partridges that

he spied at Fanda, Senegal, in 1985.

Unlike this country’s normal brown-headed, buff-breasted specimens, these were

very finely but noticeably mottled with white upon their head and neck, and

their breast was whitish. They were also rather smaller in size, but most

unexpected of all was their habitat.

A

typical stone partridge, in The Gambia,

which neighbours Senegal

(© Francesco Veronesi/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Eschewing the

rocky terrain or scrubland normally frequented by Ptilopachus, this

covey was dwelling within a small but dense area of undergrowth in a rice

field, many miles from the nearest expanse of stony ground. Owen saw a second

covey of this strange form of stone partridge at Kouniara, and this time they

were living in thick woodland, comprising a mixture of real forest and palm

trees. Yet despite their radically different habitat, their behaviour was

similar to that of typical stone partridges, scurrying rapidly across the

ground – though in this case over fallen trees and through the forest, rather

than over rocks and through scrub.

Local hunters had

informed Owen that such birds existed, but he had not believed this until he

had encountered them himself. In view of their morphological differences and

markedly distinct habitat, could these stone partridges constitute a separate

subspecies, isolated topographically from the nominate race? Bearing in mind,

however, the tragic, continuing destruction of Senegal’s wildlife habitats,

especially forests, it is to be hoped that this mystifying bird form can be

thoroughly investigated in the near future, to enable it (if still surviving)

to be saved not only from continued scientific obscurity but also from ensuing

extinction. Interestingly, I recently discovered online a vintage colour

illustration that portrays a pair of stone partridges closely matching Owen's

description, complete with white mottling upon their head and neck, plus a

whitish breast, so clearly such a form has been seen and even depicted in the

past.

A

pair of stone partridges resembling those seen by Owen Burnham in Senegal –

this vintage colour illustration was created some time between 1700 and 1880,

and is from Iconographia Zoologica (public domain)

GIANT BUSHBABY

Related to the

Madagascan lemurs and the Asian lorises, as well as to Africa's own pottos

and angwantibos, the bushbabies or galagos constitute 19 currently-recognised

species of primitive primate. Nocturnal and arboreal, they are characterised by

their large ears, long tail, and fairly small size. Currently, the largest

species are the three aptly-named greater bushbabies, with an average total

length of 3 ft, of which over

half comprises the tail.

However, Senegal may be

harbouring a rather more sizeable surprise. In June 1985, while exploring the

heart of the Casamance Forest, Owen spied a

mysterious creature resembling a giant form of bushbaby. It was the size of a

half-grown domestic cat, with pale grey fur, and was accompanied by two or

three young ones. Several years later, a similar animal was also reported from

another West African country, the Ivory Coast. And in 1994,

an assistant of bushbaby taxonomist Dr Simon K. Bearder, from Oxford Brookes University in England, encountered

and even photographed a strange cat-sized creature in Cameroon that once again

was superficially reminiscent of a giant bushbaby. Further details concerning

these perplexing extra-large prosimians can be found in my book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals.

HAIRY MAN-BEASTS

OF FOREST AND STREAM

Another

mystifying entity reported from Senegambia, and also from Guinea, but

unrecognised by science is the fating'ho. Although still believed in by the

more elderly members of native Senegalese society, younger people here tend to

discount them as mere superstition or folklore, but occasionally something

happens to make them think again.

For instance:

one day in or around November 1992, one of Owen's longtime Senegalese friends,

a youthful native entomological researcher called Malang Mane, was conducting research

in a densely forested area of northern Guinea at an altitude of about 3600

ft when he saw something that drove all thoughts of insects far

from his mind. Without warning, and completely silently, a man-sized entity

stepped out of the undergrowth only a short distance ahead of him. It was

covered in long, shaggy black hair, had a noticeably large head, and emitted a

guttural grunting sound. Most significant of all, however, was the fact that

this veritable man-beast was walking on its hind legs, and was not holding onto

any branches or foliage for support, i.e. it was fully bipedal, just like

humans. Too shocked and frightened to move, Malang watched it

approach to within a few feet of him before it ran away again.

Dramatic artistic

representation of a confrontational Australopithecus group, exhibited in Brazil

(According to Wikipedia, this artwork is in the public domain - click here for full details)

Malang is very

familiar with the West African chimpanzee, and he was certain that the creature

was not a chimp, bearing in mind that he had observed it in detail at very

close range. Nor was it a gorilla, which is not native to this region of West Africa anyway. Only

then did he realise that he must have seen one of the elusive, legendary

fating'ho.

Similar

man-beasts have been reported elsewhere in Africa too, and some

cryptozoologists have suggested that they may be surviving australopithecines -

primitive hominids that officially became extinct at least a million years ago.

Like many West African 'monsters', however, the fating'ho seems to inhabit a

twilit world midway between mythology and mystery, for it combines various

ostensibly physical features with certain purportedly preternatural ones, thus

frustrating traditional attempts at cryptozoological classification.

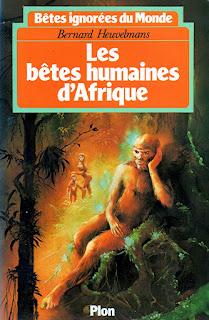

Artistic

representation of a living australopithecine, as depicted on the front cover of

Dr Bernard Heuvelmans book Les Bêtes Humaines d'Afrique, dealing with

sightings of various mystery man-beasts in this continent (© Plon Publishing –

reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

Some

eyewitnesses, for example, claim that these entities will sometimes disappear

into thin air in full view of their human observers. It is also believed that

they can fire arrows at humans that are not tangible, but are 'spirit arrows'

instead. These reputedly cause disfiguring ulcers to break out on their

victims' skin, which never heal again.

The fating'ho is

not the only mysterious man-beast reported from Senegal. Also on file

is the wokolo, which is chiefly differentiated from the fating'ho

morphologically by its yellow eyes (those of the fating'ho are red) and long

pointed beard. However, whereas the fating'ho prefers dense forests, the wokolo

is more commonly encountered near streams.

GUIAFAIRO AND

KIKIYAON - ENCOUNTERS OF THE EERIE KIND

Two of the

weirdest and most grotesque monsters reported from Senegambia - or anywhere

else, for that matter - must surely be the guiafairo and the kikiyaon.

Said to remain

hidden by day within the hollow trees and cave-ridden rocky outcrops rising

above the hot savannahs, it is during the evening that the guiafairo takes to

the wing, earning itself a fearful but memorable title - 'the fear that flies

by night'. Few people who have been unfortunate enough to receive a visitation

from this dire entity can agree upon its precise appearance. Some claim that it

is grey in colour and winged, with a human face and clawed feet - a form of

giant bat? Yet others aver that it is phantasmal, with no permanent, corporeal

form, and can even materialise through locked doors.

All confirm,

however, that its arrival is accompanied by a vile, nauseating smell that

engenders a suffocating, mind-numbing fear never forgotten by those who

experience it - always assuming that they do survive. Some of the guiafairo's

victims have died soon afterwards from a creeping, paralysing malaise, almost

as if their fear has itself acquired a lethal, physical reality.

No less deadly,

or dreadful, than the guiafairo is the kikiyaon, which is said by the Bambara

tribe to inhabit only the darkest expanses of forest, and rarely emerges from

this stygian gloom. On those occasions when it is seen, however, it is likened

to a monstrous owl, with a pair of immense wings, huge talons on its feet, and,

most notable of all, a razor-sharp spur projecting from the tip of each of its

two shoulder joints. Yet whereas its wings are feathered like those of normal

owls, the body of this awesome apparition is clothed in short, greenish-grey

fur, and it is even said to possess a short tufted tail.

An

exercise in imagining what form an encounter with the dreaded kikiyaon might

take (Pixabay/free usage)

Most native

people believe the kikiyaon to be a truly supernatural creature, rather than merely

an elusive natural one. They claim that evil sorcerers utilise this entity to

kill people, either physically or spiritually, and can even directly transform

themselves into a kikiyaon.

Yet it can give

voice to some very substantial cries. These include a deep far-reaching

grunting call that has been likened to (albeit not conclusively identified

with) that of Pel's fishing owl Scotopelia peli, a sizeable owl that is

native to Senegambia. However, there is another cry that does

not seem to resemble that of any known species of owl here, and has been

compared to the hideous shrieks of someone being slowly strangled!

Perhaps

Pel's fishing owl will one day prove to be the hitherto-unrevealed identity of

the very vocal kikiyaon? This exquisite chromolithograph was produced in 1859

by Joseph Wolf (public domain)

Intriguingly,

this is precisely the description applied to the voice of another still-unidentified,

exceedingly elusive mystery beast. Namely, the devil bird of Sri Lanka, whose

fascinating if highly frustrating case history I examine and document in

considerable detail within my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings.

Who knows?

Perhaps a real, reclusive creature, possibly even an undescribed species of

owl, originally inspired belief in the kikiyaon, but was gradually

'transformed' by superstition and folklore into the bizarre monster claimed to

exist here today. It certainly wouldn't be the first time that a seemingly

impossible creature has ultimately been shown to have a somewhat less dramatic

and hitherto unrecognised but unequivocally genuine animal at its source.

WERE-HYAENAS AND

SABRE-TOOTHS

Another

Senegalese mystery beast that may be more substantial than surrealistic is the

booa. Although only rarely seen, when it is observed the booa is usually

likened to a giant, abnormally-coloured form of hyaena. In contrast, it is very

frequently heard, especially at night. Indeed, its name is onomatopoeic, being

derived from the hideous screaming cry that reverberates loudly through the

still evening air when one of these creatures is in the vicinity.

As with the

kikiyaon, some Senegalese people are convinced that the booa is actually a

transformed sorcerer, i.e. a were-hyaena. They claim that if a booa is shot and

its trail of blood followed, it will surely lead to a human house, inside which

a man or woman will be found, bleeding profusely from gunshot wounds. (This

scenario closely echoes many medieval Western accounts of werewolves.) There is

a similar Senegalese belief regarding the mo solo - said to be a type of

were-leopard (not to be confused with the leopard-man cults).

Is

the booaa a mysterious giant hyaena, such as the supposedly long-extinct

short-faced hyaena Pachycrocuta brevirostris? (public domain)

However, reports

of the booa also readily call to mind numerous accounts from East Africa, especially Kenya, of a seemingly

allied but corporeal mystery beast variously termed the chemosit, kerit, or

Nandi bear.

Many

descriptions of this infamously ferocious, forest-dwelling creature have

likened it to a huge form of hyaena, of aberrant colouration and with a relatively

short face (click here for a recent

ShukerNature blog article dealing with the Nandi bear). Perhaps the booaa is an

occidental counterpart in Senegal?

Artistic

representation of the wanjilanko's possible appearance (I found this

illustration on the Net, but I am currently unaware of the artist's identity,

despite having made extensive online searches in relation to it – consequently

I am reproducing it here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

Due to poaching

and political unrest, in quite recent times some of Senegal's forests have

been destroyed, and its more exotic, rarer animals have become extinct. In

addition, it is possible that some particularly secretive species have actually

died out here even before their very existence was recognised by science.

During

discussions with native hunters in Senegal's depleted Casamance Forest, Owen has

learnt that they can still readily recall a huge but very mysterious form of

cat, which they refer to as the wanjilanko. According to their descriptions, it

was striped, possessed very large teeth, and was so ferocious that it could

even kill lions. Tragically, however, it appears to have died out, as have the

lions that it allegedly once attacked.

Could

sabre-tooth survival be a reality in the most remote regions of West

Africa? Meanwhile, here's one that I made earlier! (© Dr

Karl Shuker)

Reports of huge

striped cats with very large teeth and savage temperament have also been

recorded elsewhere in West Africa. In Chad, for example,

such a creature is known as the mountain tiger or hadjel, whereas further east,

moving into the Central African Republic, local tribes

speak variously of the gassingram or vassoko. Their descriptions invariably

recall Machairodus, the officially extinct African sabre-toothed tiger.

In addition, when illustrations of this prehistoric stalwart's likely

appearance in life have been shown to native hunters, they have readily

identified them as pictures of their lands' striped, toothy mystery cats (see

my books Mystery Cats of the World

and Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery,

as well as Still In Search Of PrehistoricSurvivors, for additional details).

The prospect of

sabre-tooth persistence into modern times must rate as very slim indeed.

Nevertheless, there are few places on earth more capable of sustaining such

survival beyond the reach of scientific detection than the remote,

little-explored jungle-lands of West Africa.

Proffering

a portrait of Senegal's

red-furred, leonine chakpuar (© Dr Karl Shuker – created by me from a Pixabay/free

usage image)

Also needing an

explanation are Senegalese stories of a strange long-necked red lion known as

the chakpuar, and peculiar ‘cat-wolves’ referred to as the guomna and sing

sing. To quote one of Owen's communications to me concerning the sing sing:

The "cat-wolf" is a strange concept that I have invented

really to explain the oddities of the Sing Sing which seems to have the speed

and stealth of a cat but the tenacity and stamina of a dog. It appears to have

a head like a wolf and non retractable claws. The pelage is said to be somewhat

brindled, like that of a laughing hyena [= the spotted hyaena Crocuta

crocuta] without the spots. Its tail is short and ringed. Again, this

creature inspires fear in hardy hunters and is rarely talked about in case

discussing it causes it to appear suddenly from the depths of the forest.

Except for the

short tail, this description recalls the striped hyaena Hyaena hyaena,

which is indeed native to Senegal. As this

species is normally nocturnal, and therefore not readily seen, it may have

engendered a heightened, exaggerated sense of fear among the local people, thus

explaining their dread of it and its elevation in their minds to the status of

a veritable monster - the sing sing.

THE TANTALISING

TANKONGH

While visiting Guinea, another West

African country that may still contain some intriguing zoological surprises,

Owen learnt of yet another unidentified beast, the diminutive tankongh. This

extremely shy beast is said by local hunters to resemble a small zebra, yet

lives only in the high mountain forests and is rarely seen. However, Owen was

once shown a pair of tiny dull grey hooves and some pieces of black and cream

mottled skin – the remains of a tankongh that had been killed and eaten.

Owen mentions

that according to local reports, this mysterious animal has a pair of small

canine tusks, which makes me think of the water chevrotain Hyemoschus

aquaticus. This is a small, hornless, but tusked ungulate adorned with

stripes and spots, which is native to Guinea’s lowland

forests and swamp margins. Could this known but exceedingly elusive mammal be

the identity of the tankongh, or could the latter even be a related but

scientifically-undescribed species adapted for a montane existence? And what of

the un-named, uncaptured toad, also hailing from Guinea, that reputedly

gives birth to live young – is this a new form?

Vintage

chromolithograph depicting West Africa's

handsomely-marked but extremely reclusive water chevrotain (public domain)

It was Pliny the

Elder who said: "Ex Africa semper aliquod novi" – "There is always

something new out of Africa". Judging

from the cryptic creatures documented here, all currently lurking within that

dusky borderland between reverie and reality, the intrepid cryptozoologist

would do well to heed his words, and pay a keen-eyed visit to this mysterious

continent's all-too-long-overlooked Western quarter. Who knows what

extraordinary revelations may still await formal scientific disclosure here?

This ShukerNature blog article is exclusively

excerpted from my book Dr Shuker's Casebook: In Pursuit of Marvels and Mysteries.