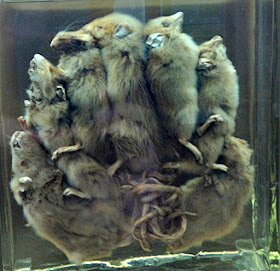

Among the most unusual but prized museum specimens are preserved aggregations of black rats Rattus rattus inextricably linked to one another by their tails - which are so thoroughly entangled that the rats have been unable to disentangle themselves and escape. A grotesque, tail-entwined aggregation of this type is termed a rat king or 'roi de rats'. This is possibly a corruption of the French 'rouet de rats' - 'rat wheel' – as the tails when straightened out radiate outwards from the central uniting knot like the spokes of a wheel radiating out from the wheel's central hub. Yet despite centuries of reports and occasional captures, the mystery of how their tails become so intertwined remains unsolved.

MORE THAN FOUR CENTURIES OF RAT KINGS

The earliest currently-documented record of a rat king dates from 1564, more than four centuries ago. It takes the form of a woodcut illustrating a poem in the monumental emblem book authored by renowned Hungarian scholar-historian Johannes Sambucus, entitled Emblemata cum aliquot nummis antiqui operis, Ioannis Sambuci Tirnaviensis Pannonii. The poem tells of a rodent-plagued man whose servant discovers seven rats with their tails inextricably tangled together, and this rat king (though not referred to by that term in the poem) is depicted as alive and in some detail within the engraving. The accuracy of the depiction shows that rat kings were known as far back as the 1500s, and suggests that it was based upon a specific example, though no written documentation of this example apparently exists.

Since then, more than 60 specimens have been recorded, spanning the time period 1612-2005, though at least 18 of them are of dubious authenticity (some rat kings have been fraudulently created as unusual - and expensive! - souvenirs for the unwary traveller or curio collector). Furthermore, despite being associated with superstitions that their discovery is a portent of the plague and other evils, several rat kings are greatly-prized exhibits in various museums.

Intriguingly, most reported rat kings are of German origin, though why this should be is unclear (unless German writers took greater pains to chronicle any such anomalous finds in their own country than writers of other nationalities have done regarding rat kings found in theirs?). The single most comprehensive source of rat king information is Martin Hart's book Rats, which devotes an entire and very extensive chapter to the subject (once again, moreover, Hart is German, and his book was originally published in German, with an English translation appearing in 1982).

Space considerations obviously prevent me from covering within this present ShukerNature blog article every single rat king on record, but a representative selection, including the most dramatic and unusual cases, appear in the following review.

A RAT KING REVIEW

The first on the total list of specimens on record is a nine-rat example that was discovered on 20 March 1612 behind a partition in a loft in Danzig (now Gdansk), Poland, by a local professor. All of the rats were adult, appeared well-fed, and were alive when found. Its details were included in a letter from the professor to a colleague in Basle, Switzerland. This was followed 71 years later by the finding of a six-rat king in Strasbourg on 4 July 1683; these rats were all juveniles.

A very remarkable example was the 18-rat king discovered on 12 or 13 July 1748 by miller Johann Heinrich Jäger at Grossballhausen (also spelt 'Gross Ballheiser') in Germany, when it fell from between two stones underneath his mill's cogwheels. Strangely, a famous, beautifully-executed copper engraving of this very noteworthy rat king depicts it with only nine rats present (unless, perhaps, the other nine are hidden beneath the nine portrayed?).

Also controversial in terms of its visual portrayal is the rat king discovered in Erfurt, Germany, in 1772. For whereas in his book Hart lists it as a 12-rat king, a detailed engraving of this example dating back to the early 1800s portrays it as containing only ten rats - but also with a very stylised, unnatural-looking knot. Consequently, this picture may have been intended merely as a general rat king representation, rather than as a specific depiction of the Erfurt example.

On 11/12 January 1774, an amazing 16-rat king was found in a windmill at Lindenau, Germany, with all of its rats still alive. After they had been killed, the king was subsequently displayed in Leipzig, and it proved to be a very popular attraction.

Even more extraordinary was the discovery made during December 1822 at the village of Döllstadt in eastern Germany, when some threshers on a farm found two separate rat kings within a hollow beam in a barn roof attic. In both of these kings, the rats were all adult, alive, and apparently healthy. One of the kings consisted of 28 rats, the other consisted of 14 rats. The threshers killed all of them with their threshing flails and then, after great difficulty, the rats in each king were separated. Of particular interest, as originally noted by a forester who witnessed the rats' separation, is that the tail of each freed rat clearly bore the impression of the tails of the other rats in its king, thus demonstrating how tightly their tails had been entwined.

The most spectacular, monstrous rat king on record, however, was discovered inside the chimney of a miller named Steinbruck at Buchheim, Germany, in May 1828. Incredibly, it contained no less than 32 rats, although they were probably not adults, which were hairless, desiccated, and inescapably bound to one another by their Gordian-knotted tails. This exceptional rat king - indeed, a veritable rat emperor! - is today a much-valued specimen in the Mauritianum, a natural history museum in Altenburg, Germany.

Another preserved rat king can be found in Strasbourg Museum. This is a ten-rat example, whose rats were all juveniles and discovered in a frozen condition under a bale of hay during April 1894 in Dellfeld, Germany. Three of the rats had bite marks, indicating that they may have been bitten by others in the king, or had been attacked in their defenceless state by free rats.

Yet another, more recent preserved example is the rat king discovered in 1907 at Ruderhausen, near Germany's Harz Mountains. It resides today in the collections of Göttingen's Zoological Institute. Indeed, this institute may once have possessed a second rat king too, obtained in the very same year, because a number of sources of rat king information list a specimen formerly held at this establishment that was reputedly found in January 1907 at the village of Capelle, near Hamm, Westphalia, in Germany, and brought to scientific attention by the local pastor, called Wigger. If these sources are correct, however, it must have since been lost, as no such specimen exists today.

A rat king consisting of eight juveniles has been on public display for several decades in a jar of preserving fluid at New Zealand's Otago Museum. Sometime during the 1930s, it fell down onto the ground, alive, from the rafters of the company shed of Keith Ramsey Ltd on Birch Street, Otago – followed swiftly by a parent rat that defended them vigorously. The rats' tails were bound together not only by one another but also by horse hair, which is used as nesting material by rats.

In February 1963, a seven-rat king was found by farmer P. van Nijnatten partly concealed under a pile of bean sticks in his barn at Rucphen, in North Brabant, Holland. In the hope of uncovering its secret, after its rats (all adults) had been killed this king was x-rayed, revealing some tail fractures and signs of a callus formation - all indicating that the knot of tails had occurred quite some time ago.

More recent still is the rat king found by some gamebird rearers on 10 April 1986 in the municipality of Mache near Aizenay Vendée, France, and now preserved in alcohol at the natural history museum at Nantes. This king was originally composed of 12 rats, but three subsequently became detached, and it is the resulting 9-rat version that is preserved. The only other preserved French rat king is one that was discovered in November 1889 at Châteaudun and duly presented to its museum where it is still retained today; photographs of it show that it contains six rats, but I have read reports testifying that there were seven originally.

Most recent of all, however, is an Estonian rat king, consisting of 16 rats, nine or so of which were still alive when the king was discovered alive by farmer Rein Kõiv on 16 January 2005, squeaking loudly upon the sandy floor of his shed in the village of Saru. Kõiv killed them all, and on 10 March 2005 the king was taken to the Natural History (Zoological) Museum at the University of Tartu, where it was preserved in alcohol and is now on display. Prior to this, however, two of the rats had been eaten by a predator and a third had been thrown away by Kõiv himself. Two other Estonian rat kings have been reported, both during the 20th Century, but neither of them was preserved.

A KNOTTY PROBLEM

A number of explanations for the formation of rat kings have been offered. One of the most popular is that if rats huddle together for warmth in damp or freezing surroundings, with their tails pressed against one another, their tails become sticky (possibly from the rats' own urine) and soon adhere to or become frozen against one another, becoming ever more entangled and fixed as the rats thereafter strive to pull free. However, if this were indeed the correct explanation, being such a frequent, commonplace scenario it would surely engender far more examples of rat kings than have been documented so far?

Another notion is that a rat king is actually a single litter whose members' tails became entangled while the rats were still in their mother's uterus. If this were true, however, it seems highly unlikely that they would survive to adulthood, as they would be unable to obtain much food, yoked together in this manner. Yet most rat kings on record feature adult specimens, and ones that are often healthy when found.

Equally intriguing is why all but three of these murine kings feature black rats Rattus rattus. There is none involving the much more common brown rat R. norvegicus, but this may be due to the fact that the brown rat's tail is shorter, thicker, and less flexible than that of the black rat. Indeed, the only rat exception to the black rat rule is an Indonesian king consisting of ten young Asian field rats R. brevicaudatus, discovered on 23 March 1918 in Buitenzorg (aka Bogor), Java. In addition, a single king composed of house mice Mus musculus has been recorded (documented in a Russian book dealing with mice and rats). So too has one field mouse king, consisting of several juvenile long-tailed field mice Apodemus sylvaticus, found at Holstein, Germany, in April 1929.

SQUIRREL KINGS

However, not all rodent kings involve rats or mice. At least 17 naturally-occurring squirrel kings have also been recorded (certain cruel, vile cases of squirrels having been forcibly tied together via their tails by human sadists are also known, tragically). Yet the concept of bushy-tailed squirrels becoming entwined together in this way seems even more incongruous than that of rats.

A seven-squirrel king was discovered in a South Carolina zoo on 31 December 1951. Tragically, however, two of its members were dead, a third was dying, and its four other members could only be separated by cutting off their tails above the knot. Curiously, two other squirrel kings have been found here over the years, and all during cold snowy weather, implying that the squirrels had huddled together for warmth.

A king containing six young squirrels was spotted by schoolgirl Crystal Cresseveur in a hedge outside her home in Easton, Pennsylvania, on 24 September 1989. Although they were eventually rescued, their tails could not be disentangled. A five-squirrel king (two members of which were albinos) fell out of a tree by Reisterstown Elementary School in Baltimore, Maryland, on 18 September 1991, but these were successfully separated as their tails were linked to one another only indirectly, with sticky tree sap, tangled hair, and nest debris. In Europe, at least two kings of red squirrels Sciurus vulgaris have been recorded - one in August 1921, the other on 20 October 1951 (which was later preserved).

In July 1997, what looked at first like a huge hairy spider was spotted under a tree in Brantford, in Ontario, Canada, but a closer look revealed that it was actually a squirrel king, composed of five young squirrels whose tails were braided together right up to their bases. They were taken to a vet, Cathy Séguin, who freed them, but she feared that the loss of circulation that their tails had suffered would result in part of each tail dying.

CAT KINGS

Analogous to rat kings, mouse kings, and squirrel kings is the even more obscure phenomenon of cat kings. Here, however, it is the umbilical cords of kittens in newborn litters that are tangled and intertwined, not their tails. Such curiosities are extremely rare, but at least a dozen have been documented in the scientific literature.

Perhaps the best known is the cat king recorded in October 1937 at Rennes, in Brittany, northwestern France. It consisted of a litter of eight small kittens, seven of which (males and females) were held closely together via their entangled umbilical cords. Indeed, the entanglement was so complex that even the left hind legs of two of the kittens had become bound up to one another. The kittens in this cat king were discovered dead, but it is not known whether their cords' complicated intertwining had occurred before the litter's birth or afterwards.

A cat king recorded in 1841 consisted of five unborn kittens whose entwined umbilical cords were still fixed to their mother's placenta. This shows that such entanglement can indeed occur while the kittens are still in the womb. The earliest cat king known to me is a five-kitten specimen from 1683, found in Strasbourg, France.

Today, the mystery of how rat kings are formed remains exactly that – an unresolved anomaly whose reality has spanned centuries but whose secret still awaits disclosure. Some sceptics have cynically suggested that the phenomenon is simply a hoax, that the knotting together of the tails of rats in a king is clearly the result of deliberate human activity.

Bearing in mind, however, that most of the rat kings on record were discovered when their rats were very much alive and often still in good health (albeit hungry and frightened), and that the tail knots were exceedingly complex, all that I can say in response to these sceptics is that they have certainly never attempted to tie the tails together of several (not to mention 18 or 32!) live, healthy rats. If they were ever brave (or foolish) enough to try to do so, their cynicism would very swiftly vanish – along, quite possibly, with several of their fingers!

UPDATE: 3 November 2021 – TWO LIVING RAT KINGS FILMED!

Although there have been various filmed, living examples of squirrel kings, there has never been to my knowledge any film footage obtained of a living rat king – until recently, that is. On 21 August 2021, Russian farmer Alibulat Rasulov discovered a live rat king in one of his flooded watermelon fields, near Stavropol on southwestern Russia, which he was able to film and upload in two sections onto Instagram. The king consisted of five small rats. Unlike most rat king cases, moreover, this one had a happy ending, inasmuch as Rasulov not only lifted the king out of the water but when placed on dry land he was also able to disentangle the five rats' tails, enabling them to run away, freed.

And now, today, various media reports have appeared online concerning a second living, squirming collection of rats bound tightly to one another via their inextricably – and inexplicably – intertwined tails, i.e. another classic rat king, which had recently been found by qualified vet Johan Uibopoo inside the chicken coop of his mother at her home near Tartu, Estonia, after he had received a distressed phone call from her. The rat king proved to consist of no fewer than 13 rats, and Uibopoo succeeded in obtaining some excellent close-up film footage (click here) of the grotesque conjoined congregation. However, two of its rats were already dead by the time that he'd arrived. Dr Andrei Miljutin from the University of Tartu's Natural History Museum, who'd previously documented an Estonian rat king, agreed to take this latest example. According to traditional folklore, the appearance of a rat king foretells an impending plague – but in both of these particular instances the rat king's appearance was evidently somewhat late, judging from the worldwide arrival more than a year earlier of a very significant plague, Covid-19...

This ShukerNature blog article is expanded from my book A Manifestation of Monsters.

Fascinating, and extremely well researched, as usual, Karl. Not sure I like *any* of the explanations, but I certainly have no alternative to offer!

ReplyDeleteThanks Richard, I always greatly value your comments and praise for my researches and writings.

DeleteI sometimes keep electrical cables in a bag, putting them in without coiling or tying them to prevent tangling. Tangling can happen but is surprisingly uncommon. As a living species would be at a disadvantage if it commonly got tangled, I suggest rats commonly entwine their tails but very rarely become entangled. I can't figure out why it's so rare, especially as they appear to be able to turn around in their own length, meaning both ends of the creature may be involved in causing the tangle. Perhaps they have some instinct mild enough to be occasionally violated. Perhaps rare individuals lack the instinct.

ReplyDeleteGlad you saw that recent example, Karl and have updated your blog. You will probably have to go back now and change the "latest example" comment made for the 2005 case!

ReplyDeleteThanks Bob, but it would be superfluous and potentially confusing to the article's main text to modify it in relation to material contained in an update. By definition, update material is material obtained AFTER the main text has been written and uploaded, and is therefore presented separately from and not mentioned within the main text. So the most recent case when the main text was uploaded remains the 2005 Estonian one, with the new case the specific focus of the (post-main text) update.

DeleteHi Karl, I found the following video online, from Russia, 2023, which may interest you:

Deletehttps://www.newsflare.com/video/467613/a-resident-of-stavropol-in-a-garden-with-watermelons-discovered-the-rat-king

I found the following video tonight, from Eastern Europe, posted 2023.

Deletehttps://www.newsflare.com/video/467613/a-resident-of-stavropol-in-a-garden-with-watermelons-discovered-the-rat-king