The eurypterids or sea scorpions of prehistory are unquestionably among the most extraordinary, physically spectacular creatures known exclusively from the fossil record. They consist of a long-extinct group of arthropods – that incomparably diverse assemblage of invertebrates united morphologically (but no longer taxonomically within a single phylum) by their jointed limbs. Including among their number the largest and most spectacular of all arthropods, attaining a total length of up to 8 ft in one species (Jaekelopterus rhenaniae), the sea scorpions were only distantly related to modern-day scorpions, as they were much more closely allied to the horseshoe crabs. They had reached their zenith of evolutionary of development by the late Silurian Period (approximately 420 million years ago) and had disappeared entirely from the fossil record by the close of the Permian (around 170 million years later), victims of the mass extinction that occurred at that time.

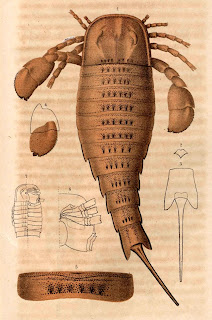

Most sea scorpions were generally elongate - commencing with a broad prosoma (the combined head and thorax) whose rounded head sported a distinctive pair of laterally-sited compound eyes and elongated mouth, and whose short thorax bore six pairs of limbs. One pair, the chelicerae, were jaw-parts (which attained an exceptional degree of development in Pterygotus species, resembling pincer-like grasping organs). The others were true legs (which in some species were so stout that they may have enabled these particular forms to walk on land).

Of those true legs, the most posterior pair was much larger and flatter than the rest, terminating in oval plates or paddles - undoubtedly constituting the principal swimming organs, but possibly serving as anchors too, or as scoops for digging up mud on the sea bottom where these creatures may have rested or hidden themselves. These wider legs earned the sea scorpions their scientific name - 'eurypterid' translates as 'broad wing', alluding to the wide paddles.

The abdomen or opisthosoma was divided into two morphologically distinct sections. The forepart, known as the mesosoma, consisted of seven squat segments. The posterior part or metasoma consisted of five tapering cylindrical segments, the last of which bifurcated into two lobes - between which, concluding the sea scorpion's morphological roll-call, arose a long pointed spine (or, in some species, a short flat plate) called the telson or tail.

During their evolution, the sea scorpions adapted to living in brackish waters too, and even entered freshwater. Indeed, based upon some exceptional eurypterid fossils unearthed during the 1980s at East Kirkton in West Lothian, Scotland, palaeontologists believe that certain sea scorpions might even have been terrestrial. And if their lineage has persisted into the present day, 245 million years of intervening evolution could have engineered many other changes too, yielding creatures quite different in form and lifestyle from their Permian predecessors.

But what has all of the above information on sea scorpions to do with the mystery creature under consideration in this present ShukerNature article? In reality, nothing at all, were it not for a very confusing similarity of names, which, until I investigated it, had prevented the true nature of the creature in question from being recognised for what it truly is. Happily, all will now be revealed, in the curious case of the East Sussex sea scopium.

I was first alerted to the mystifying sea scopium by way of a short but tantalising newspaper report, written by reporter John Ogden, that appeared in my local evening newspaper, the Sandwell Express and Star (Wolverhampton), on 2 May 1986, p. 2. It concerned a TV programme that had been screened the previous evening, 1 May.

Channel 4, a British television station, had broadcast a little-known true-life film that had been made in 1972 and was entitled The Moon and the Sledgehammer. Its subject was the Pate family, whose home was situated deep in some woods near Newhaven in East Sussex, southern England, and whose patriarch was Old Man Pate.

In this film, Old Man Pate recollected seeing a marine creature that he referred to as a 'sea scopium'. According to his description, it "looks like an old ship's sailing cloth in the water...They're black...It's got a head like a frog, but it's all goldy colour round, and its eyes stick out a bit, bulge fashion...It was about 7-8 ft under the water".

Pate had considered pulling it out of the sea to observe it more closely, but when he saw its large mouth, and realised that it was looking at him, he changed his mind. Afterwards, however, he regretted this, and in the film he announced plans to build a semi-submersible boat in which to look for the creature again. But what might it have been? Surely not a living sea scorpion??

Although the term 'sea scopium' naturally evokes images of eurypterids, there is a much simpler explanation available here. Pate's account recalls a fish called the sea scorpion – Myoxocephalus scorpius. Up to 2 ft long and black when fully mature, also referred to as the shorthorn sculpin, and a member of the taxonomic family of fishes known as cottid sculpins, this is a large-mouthed, frog-faced lurker among stones and seaweed on rocky seafloor with mud or sand.

This species is found in the English Channel, and the Atlantic north of Biscay, as well as the Arctic basin including the Siberian and Alaskan coasts. True, its head is not golden, but in the film Pate stated that the sun was shining down through the water, so this no doubt gave the creature's head a golden sheen. Exit the 'sea scopium' from any further cryptozoological consideration.

Many years ago, in a report describing a new 3-ft-long species of Mixopterus sea scorpion, Norwegian palaeontologist Prof. Johan Kiaer recalled the thrill of its discovery:

I shall never forget the moment when the first excellently preserved specimen of the new giant eurypterid was found. My workmen had lifted up a large slab, and when they turned it over, we suddenly saw the huge animal, with its marvelously shaped feet, stretched out in natural position. There was something so lifelike about it, gleaming darkly in the stone, that we almost expected to see it slowly rise from the bed where it had rested in peace for millions of years and crawl down to the lake that glittered close below us.

No doubt cryptozoologists share a similarly dramatic dream – to haul up a living sea scorpion from the depths of the oceans or even from the muddy bottom of a very large freshwater lake. Certainly, there have been some claims of this nature made down through the years in relation to various unidentified aquatic mystery beasts. And who knows – somewhere out there, perhaps there really are some post-Permian, present-day eurypterids, indolently lurking in scientific anonymity? Yet if the terminological tangle disentangled here that had hitherto hindered the delineation of these palaeontological sea scorpions from their modern-day piscean namesake is anything to go by, however, this prospect seems no more likely than the resurrection of Kiaer's fossilised specimen from its rocky bed of Silurian sandstone.

My sincere thanks to longstanding friend and crypto-colleague Sally Watts for kindly making available to me for personal viewing a copy of The Moon and the Sledgehammer after I'd mentioned reading the above newspaper cutting referring to its sea scopium.

Fascinating critters!

ReplyDelete