What's in a name? Not a lot, sometimes. Or, to put it more poetically: the naming of books – and animals – is a difficult matter, it isn't just one of your holiday games, as T.S. Eliot almost said.

Take, for instance, a book written by English diplomat, Conservative MP, and Oriental scholar Edward Backhouse Eastwick (1814-1883), published in 1849, and entitled Dry Leaves From Young Egypt. With a title like that, one might well be forgiven for assuming it to be a volume devoted to the land of the pyramids and sphinx, but in reality its subject is the author's journey in 1839 through Sindh, the most southeasterly of Pakistan's four provinces. Similarly, a section within this same book entitled 'Magar Taláo – the Alligator Lake' is not about alligators at all, which are not native to Pakistan, but concerns crocodile instead, which are native here.

I first learned about Magar Taláo about 30 years ago, from a thoroughly fascinating, exquisitely illustrated compendium volume from 1885 entitled The World of Wonders: A Record of Things Wonderful in Nature, Science, and Art that I'd recently purchased at a book fair, and which was packed with the most intriguing, unusual, and sometimes truly bizarre subjects, often excerpted from earlier works that nowadays are all but forgotten. In the case of Magar Taláo, this compendium's coverage consisted of what turned out upon my later checking of it to be a direct quote of the entire relevant passage from Eastwick's afore-mentioned book.

Moreover, as it is such an interesting but nowadays rarely read passage, I have decided to do the same with it here on ShukerNature, because I feel sure that it will interest my blog's readers just as much as it did with me when I first read it all those years ago in The World of Wonders, and then subsequently re-read it in its original source. So here it is, quoted in full directly from Eastwick's Dry Leaves From Young Egypt (but please bear in mind that the so-called alligators referred to in it are actually crocodiles, and that it is set in Pakistan, not Egypt!):

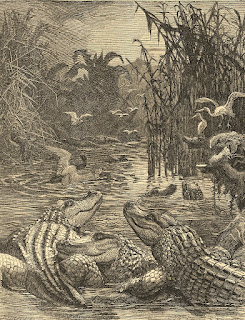

One of my first expeditions after reaching Caráchi [Karachi] was a visit to the Magar Taláo, as it is called, or Lake of Alligators. This curious place is about eight miles from Caráchi. and is well worth inspecting to all who are fond of the monstrous and grotesque. A moderate ride through a sandy and sterile track varied with a few patches of jungle, brings one to a grove of tamarind trees, hid in the bosom of which lie the grisly brood of monsters. Little would one ignorant of the locale suspect that under that green wood in that tiny pool, which an active leaper could half spring across, such hideous denizens are concealed. "Here is the pool," I said to my guide rather contemptuously, "but where are the alligators?" At the same time I was stalking on very boldly with head erect, and rather inclined to flout the whole affair, naso adunco. A sudden hoarse roar or bark, however, under my very feet, made me execute a pirouette in the air with extraordinary adroitness, and perhaps with more animation than grace. I had almost stepped on a young crocodilian imp about three feet long, whose bite, small as he was, would have been the reverse of pleasant. Presently the genius of the place made his appearance in the shape of a wizard-looking old Fakir, who, on my presenting him with a couple of rupees, produced his wand — in other words, a long pole, and then proceeded to "call up his spirits." On his shouting "Ao! Ao!" "Come! Come!" two or three times, the water suddenly became alive with monsters. At least three score huge alligators, some of them fifteen feet in length, made their appearance, and came thronging to the shore. The whole scene reminded me of fairy tales. The solitary wood, the pool with its strange inmates, the Fakir's lonely hut on the hill side, the Fakir himself, tall, swart, and gaunt, the robber-looking Bilúchi by my side, made up a fantastic picture. Strange, too, the control our showman displayed over his "Lions." On his motioning with the pole they stopped (indeed, they had already arrived at a disagreeable propinquity), and, on his calling out "Baitho," "Sit down," they lay flat on their stomachs, grinning horrible obedience with their open and expectant jaws. Some large pieces of flesh were thrown to them, to get which they struggled, writhed, and fought, and tore the flesh into shreds and gobbets. I was amused with the respect the smaller ones shewed to their overgrown seniors. One fellow, about ten feet long, was walking up to the feeding ground from the water, when he caught a glimpse of another much larger just behind him. It was odd to see the frightened look with which he sidled out of the way evidently expecting to lose half a yard of his tail before he could effect his retreat. At a short distance (perhaps half a mile) from the first pool, I was shewn another, in which the water was as warm as one could bear it for complete immersion, yet even here I saw some small alligators. The Fakirs told me these brutes were very numerous in the river about fifteen or twenty miles to the west. The monarch of the place, an enormous alligator, to which the Fakir had given the name of "Mor Saheb," "My Lord Mor," never obeyed the call to come out. As I walked round the pool I was shewn where he lay, with his head above water, immoveable as a log, and for which I should have mistaken him but for his small savage eyes, which glittered so that they seemed to emit sparks. He was, the Fakir said, very fierce and dangerous, and at least twenty feet in length.

What a fascinating if frightening vista the Lake of Alligators must have been to the previously imperious, unimpressed Eastwick, and, echoing his own viewpoint afterwards, how surreal a scene it must have seemed – the product of some fevered nightmare, no less – featuring a primeval phantasmagorical world bedeviled by the deadliest of dragons who remain lulled only by the spellbinding skills of the almost mystical, magical fakir in their midst, a veritable crocodile whisperer, in fact!

Finally, for everyone reading this blog article of mine who shares my passion for titillating trivia: the first recorded use in English of the Arabic word 'kismet', meaning destiny, fate, or simply luck, was by none other than a certain Edward Backhouse Eastwick (who spelled it 'kismat'), in – yes, you've guessed it – Dry Leaves From Young Egypt. There's a future quiz question lurking in there somewhere!

Entertaining and informative article, as always, Dr. K.

ReplyDeleteBTW, is it actually a "congregation" of crocodiles? It struck me with your interest in group animal names (pod of whales, etc.) you would choose your captioning carefully.

What a scene! Just reading it was a thrill! :)

ReplyDeleteThat's how I felt when I first read it, so I thought that others may enjoy it too.

DeleteThanks Ron. Sadly, I've never encountered a collective noun for crocodiles, so when congregation popped into my head, it seemed as good a choice as any, especially as it was alliterative, which many genuine collective nouns for animals are.

ReplyDeleteApparently a group in the water is called a "float" and a group on land is called a "bask"

ReplyDeleteInteresting! However, a bask of crocodiles doesn't have the same impact or verbal rhythm, I feel, as a congregation of crocodiles, and as for a float, well...

DeleteA Luggage Of Alligators / A Cavalcade Of Crocodiles

ReplyDeletePerhaps?

Sounds good!

Delete"I had almost stepped on a young crocodilian imp about three feet long, whose bite, small as he was, would have been the reverse of pleasant."

ReplyDeleteThat line tickled me no end. I love florid Victorian prose.

Это действительно были аллигаторы в Египте , я верю это потрясающе 💥

ReplyDelete