They say that good things come in pairs, so after the very favourable response recently received by my first ShukerNature Picture of the Day posted by me for quite some time (click here to access it), without further ado I am very happy to proffer a second one right now. Namely, the dramatic and exceedingly impressive but previously-unpublished portrait by American scholar/wildlife artist Wayne Patton (kindly forwarded to me earlier this year upon his behalf by his daughter, Alison Fielding) of one of prehistory's most spectacular mammals – the Irish elk, also known very aptly as the giant deer, and scientifically as Megaloceros giganteus.

Famed for the adult male's immense antlers, this awe-inspiring species was traditionally believed to have become extinct throughout its Eurasian distribution range during the Pleistocene epoch, i.e. prior to the onset of the Holocene, approximately 10,600 years ago. However, within my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (1995), I presented some intriguing evidence for its possible survival into the early Holocene (including mention of a mysterious, still-unidentified European beast named the schelk or shelk that may allude to Holocene representatives of Megaloceros).

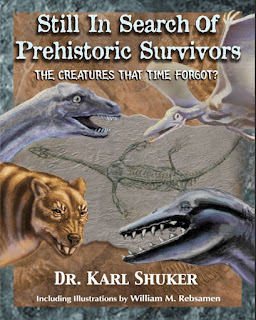

Moreover, some years later, as I duly updated in a ShukerNature article (click here) as well as in my subsequent book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors (2016), conclusive evidence for this species' Holocene survival in two widely separate Eurasian localities – the Isle of Man off the British mainland, and western Siberia in far-eastern Russia – was indeed obtained.

Inspired by my writings as well as those of many others dealing with this magnificent species, together with all manner of artistic representations of it, including cave paintings, and being an accomplished artist himself, Wayne decided to prepare his own entirely original reconstruction of its likely appearance in life, and when it was complete he very kindly offered me the opportunity to reproduce it exclusively on ShukerNature, which I was only too happy to accept. And so, showcased above as a wonderful ShukerNature Picture of the Day, is Wayne's stunning adult male Megaloceros painting, together with his verbatim account below of how he came to prepare it, his influences, and personal thoughts and ideas concerning Megaloceros, presented once again with his kind permission.

[Incidentally, please note that Wayne is using the term 'shelk' in his account merely as a common name for Megaloceros, rather than claiming a direct link between the latter deer and the mysterious still-unidentified beast of that name.]

My name is Wayne Patton, I am a botanist and soil scientist by training and experience. I worked a career for the US Forest Service. I also worked in Mexico, Canada, and collaborated with groups from Romania, and Israel. I am a big game hunter and I took game with ancient systems like the bow and arrow and atlatl darts. I also tanned my own hide and made all manner of leather goods like saddle, tack, etc… Art has been a hobby for as long as I can remember. Now I am too old to hunt, so I spend a lot of time painting and selling my work through several galleries. I got very interested in the Megaloceros giganteus (shelk) through both my hunting and art experiences. I decided to paint a bull shelk as exampled above, starting with photos of mounted skeleton in museums in Ireland, Germany, and Scotland. There are even a couple mounted skeletons in the US that were obtained from Ireland. I fleshed out the bones based on my art experience as well as butchering big game animals like the American elk as well as mule deer, goats, sheep, and some African animals like the kudu. This part was easy, however, virtually all paintings of shelks by Charles R. Knight, who did early work for the Chicago Museum of Natural History, as well as the paintings available on the internet, are sourced from the zoo, mostly, red deer and American elk. The artists painted these fat animals that are standing around at half-mast from eating the wrong diet and being trapped, and then showing them with the giant horns of the giant shelk. Perhaps the best artwork is by the current great Dutch painter Rien Poortvliet [but] he copied the colors of the red deer and missed key anatomical features like the Adams apple and shoulder hump of the real shelk. What about the color? All paintings seem to be copies of the red deer and American or Mongolian elk – is this correct?

I thought not, so I did a bunch of research to find out if any information exists and I stumbled on to a fabulous book called The Nature of Paleolithic Art by Dr R. Dale Guthrie, who was a professor at the University of Alaska. He visited caves in France, Northern Spain and Italy, as well as museums containing engravings of animals on rocks, bones, and ivory from sites in Europe. This formed a basis for his reconstruction of the bull and cow shelks. He also did a lot of work comparing Pleistocene cave art with animals that survived the Pleistocene extinctions like the Chamois, the Reindeer and the Muskox and found this art to be very accurate and can be relied upon to help make decisions about color and animal appearance. The early people lived with the animals and were keen observers and used their knowledge to hunt them, maybe hastened extinction in some cases. So, I used my firsthand knowledge of using skeletal remains to flesh out realistic animal anatomy, and I used most of Dr R. Dale Guthrie’s conclusions from his experience looking at Pleistocene art to get the best color information. My try at a painting of the Bull Shelk is enclosed.

Give me feedback of what you all think!

Also, use Amazon on the internet to track down copies of the book I used for reference (The Nature of Paleolithic Art).

Also, have a look at Rien Poortvliet in his book A Journey to The Ice Age (mammoths and other animals of the wild).

Now, back to some ideas of why many shelk remains and those of perhaps of red deer or European elk (American Moose) have holes knocked in the top of their skulls. These animals were herded in to marl pits and peat bogs where they became mired and trapped after which early people, especially in Ireland, went out and killed them where they were. Then they butchered out the best cuts of meat including the heart, liver, and tongues. Along with the brains, all of which were considered delicacies as I have on occasion. Use the 'Meat Eater' series on Netflix as a reference. The main use for brains, however, was not eating even though they are good! The primary reason for use is stabilizing and tanning leather, as I have done also. Leather has been used since the Pleistocene to make all kinds of clothing, gear and weapons. Use of brains or urine can be a smelly operation.

Wayne has raised some very interesting points here. In particdular, it is certainly true that observing cave paintings can offer various visual clues to the physical appearance of prehistoric beasts that cannot be procured from fossils alone. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the apparent presence of striped markings on the body of the cave lion, as depicted in cave paintings of this extinct felid. So it is very significant that Wayne's Megaloceros painting has incorporated information encapsulated in these early firsthand eyewitness artworks.

Additionally, Wayne's information concerning the use of brains for tanning leather does indeed offer at least a partial explanation for the skull holes observed in Megaloceros remains that I documented in my first Prehistoric Survivors book and subsequently reiterated in my second one as well as my ShukerNature article. And as it was entirely new to me, this information is very welcome.

In short, I am delighted to be able to share with you Wayne's extremely striking, wholly original interpretation of what the adult male Megaloceros may have looked like in life, and his input to what is known about the use by human hunters of the brains extracted from the skulls of butchered deer that may well have applied to this prehistoric species.

Once again, I thank Wayne most sincerely for permitting me to share all of this here on ShukerNature, and also his daughter Alison for kindly making contact with me in order to bring Wayne's work to my attention.

For an extensive coverage of possible and definite examples of Megaloceros post-Pleistocene survival, be sure to check out my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors.

Familiar with the Irish Elk but not the "shelk" cryptid let alone the explanation of it as a surviving Irish Elk... this is interesting!

ReplyDelete