In Part 1 of this ShukerNature article (click here to read it), I recalled the traditional lore appertaining to an Irish mystery beast known as the dobhar-chú or master otter, and I also documented a seemingly true but fatal confrontation between one of these supposedly savage, bloodthirsty beasts and a woman on the shore of Glenade Lake in northwestern Ireland's County Leitrim – with the avenging slaughter of the murderous dobhar-chú by her husband actually carved for all to see on her still-existing gravestone in a local cemetery.

This remarkable incident allegedly occurred almost three centuries ago, back in 1722, but as I shall now reveal here in Part 2, encounters with large unidentified creatures in northwestern and western Ireland that bear much more than a passing resemblance to the dobhar-chú have also occurred in modern times – and, indeed, are still doing so.

The origin of a folk story featuring a bizarre-sounding specimen of dobhar-chú that reputedly sported a long horn on its head like a lutrine unicorn, County Sligo in the Republic of Ireland's northwestern portion is sandwiched between County Leitrim to the right, and County Mayo to the left. Several islands are present off the western coast of Mayo, including Achill (Ireland's largest coastal island, but attached to the mainland by a bridge), whose principal cryptozoological claim to fame is Sraheens (=Glendarry) Lough. This is a small, circular lake, approximately 400 ft in diameter, very windswept and isolated, which is said to be frequented by strange water monsters.

Most of Ireland's aquatic cryptids are of the 'horse-eel' variety – i.e. sinuous eel-like entities but with horse-like heads. The Sraheens Lough monster, however, is apparently very different.

At around 10 pm on the evening of 1 May 1968, two local men, John Cooney and Michael McNulty, were driving past this lake on their way home when suddenly an extraordinary creature, shiny dark-brown or black in colour and clearly illuminated by their vehicle's headlamps, raced across the road just in front of them and vanished into some dense foliage nearby. They estimated its height at around 2.5 ft and its total length at 8-10 ft, which included a lengthy neck, and a long sturdy tail. It also had a head that they variously likened to a sheep's or a greyhound's, and four well-developed legs, upon which it rocked from side to side as it ran. Needless to say, its fully-formed legs and long tail readily eliminated any possibility that it was a seal that had come ashore onto Achill from the coast. Just a week later, a similar beast crawled out of the lake and climbed the bank as 15-year-old Gay Dever was cycling past, shocking him so much that he dismounted to watch it go by. It seemed to him to be much bigger than a horse, and black in colour, with a sheep-like head, long neck, tail, and four legs (of which the hind ones were the larger). Other sightings were also reported during this period, but the identity of the animal(s) was never ascertained.

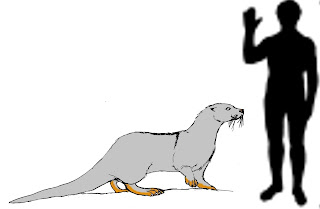

In the 13-volume encyclopedia, The Unexplained, edited by Peter Brookesmith, and first published in part-work form during the early 1980s, an unnamed artist's reconstruction of the Sraheens Lough monster originally appeared in an article on Irish lake monsters written by veteran unexplained mysteries chroniclers Janet and Colin Bord but is nowadays readily accessible online. The illustration was based upon the eyewitness accounts given above for this monster, but as can be seen here it also happens to be exceedingly similar to the Conwall gravestone's depiction of the dobhar-chú! Both share a sleek body and powerful hindquarters, long slender tail, lengthy but not overly elongate neck, distinct paws, and relatively small head. Indeed, one could easily be forgiven for assuming that the two illustrations had been based upon the same animal specimen (let alone species). Could such an arresting degree of morphological similarity be nothing more than a coincidence, or is the dobhar-chú still in existence amid the countless lakes of the Emerald Isle?

Cryptozoological sceptics have pointed out that with a circumference of only 1,200 ft, surely Sraheens Lough is too small to support water monsters of this nature. However, anything capable of running across roads on four sturdy limbs is equally capable of moving from one lake to another, not residing permanently in any one body of water - which could explain why sightings of monsters in Sraheens Lough are sporadic rather than regular.

Some very interesting additional reports of modern-day Irish cryptids resembling giant otters can be found in a fascinating book entitled Mystery Animals of Ireland (2010), authored by longstanding Celtic cryptozoology specialists Gary Cunningham and Ronan Coghlan. For example, some time in 1999-2000 near to Portumna in County Galway (south of County Mayo), Patrick Sullivan from Cleggan, Connemara, was driving along the N65 towards Loughrea when he suddenly saw an unfamiliar-looking animal wandering on the opposite side of the road. Curious to see more of this creature, he was able to turn around and drive back, and later reported that it resembled an otter but was larger and darker. As he watched, it moved off the road and disappeared into some undergrowth. In around 2001, the Sraheens Lough monster reared its otter-like head again, with a new, recent sighting featuring in a debate concerning this mystery beast that was broadcast on Radio na Gaeltachta. But the most significant recent sighting took place during April-May 2003, on Omey Island, in Connemara, County Galway, and featured Waterford artist Sean Corcoran and his wife.

In October and November 2009, Sean contacted me to provide me with details of their sighting on this island, and it was also documented by Gary and Ronan in their book. Omey contains two freshwater lakes, and is accessible on foot when the tide is out. Sean and his wife were camping on Omey, near to Fahy Lough, the larger of its two lakes, when at around 3 am one morning they were alerted to a strange yelping cry coming from the sand dunes at the lake's western side. Armed with a torch, they set out to investigate, and encountered just 2-3 yards away an animal described by Sean as being larger than his pet Labrador dog. The creature speedily swam across the lake to its furthest side, where it then emerged, clambered onto a large rock, and reared up onto its hind legs. In this pose, it was estimated by Sean to be around 5 ft tall, and was observed to be dark in overall colour but sporting orange-red flipper-like feet. It then turned away and disappeared into the darkness, leaving Sean and his wife to return to their tent, thoroughly bemused by what they had just seen.

Tellingly, as pointed out by Gary and Ronan in their coverage of this sighting, Fahy Lough is only about 20 yards from the sea at Omey's sheltered western point, with the marine waters around this island being plentifully supplied with available food for such a creature, including fishes and crustaceans. Moreover, during previous camping holidays on Omey, Sean had seen animal scats near Fahy Lough that when examined were found to contain the remains of crabs and other shellfish.

Otters are well known for rearing up onto their hind legs to obtain a better view of something of interest to them, so the Omey beast's behaviour certainly accords with that. However, its size is far bigger than one would expect a normal Irish otter to be, and its orange-red feet (which to give the appearance that they were flippers suggests that they were extensively webbed) are also wholly atypical for the latter.

In view of how near the unidentified beast seen by Sean was to the sea, it is nothing if not interesting to note that a mysterious but rare species referred to locally as a 'sea otter' reputedly once inhabited a large stagnant pool in one of Achill Island's famous seal caves, the cave in question being known as Priest's Hole. This 'sea otter' was said to be distinguished from normal otters by its large size and uniformly black or near-black pelage, broken only by a single white patch on its throat. The source of this information was Harris Stone, an elderly man who was living close by there in around 1906.

Equally intriguing is a large taxiderm otter spotted by Gary Cunningham when visiting an Irish pub in April 1999. The pub is called Hynes Pub, and is situated in the village of Crossmolina, in County Mayo. What attracted Gary's attention to the stuffed otter, placed on top of the pub's television, was not only its size (he estimated it to be about 4.5 ft long), but also its noticeably elongate form, with a remarkably lengthy neck, slightly elongated hinds limbs, long bushy tail (not a typical otter accoutrement!), and its very dark, almost black-coloured fur. Being with his family, Gary did not have the opportunity to gather details concerning the history of this curious specimen, but he was struck by how different it was from the usual Irish otter while comparing surprisingly closely to the appearance of the dobhar-chú carved upon the gravestone of Grace Connolly.

Although he was well aware that morphological distortions can certainly occur during the preparation of taxiderm specimens, having inspected this otter closely Gary was not convinced that its highly distinctive form could be explained away in this manner. He was able to snap two colour photographs of it, which he has most kindly made available to me, enclosing them with a very detailed letter on the subject of Irish water monsters that he wrote to me on 29 May 2000, and as they reveal here it is indisputably unusually elongate in form (though naturally we have no idea how much this may be due to the taxidermist's rendition of the specimen's skin in stuffed form as opposed to its original, natural state). Clearly, therefore, it would be beneficial for this enigmatic specimen to be subjected to a formal zoological examination, perhaps even taking from it a small tissue sample for possible DNA analysis, and to enquire from its owners its background history.

Mystery beasts reminiscent of the dobhar-chú have even been reported occasionally from northern and northwestern Scotland, although these Caledonian counterparts have attracted much less attention, even from cryptozoologists (but click here to read my earlier ShukerNature article re such beasts). One of the earliest but most intriguing accounts is contained in The History of the Scots From Their First Origin (1575), authored by Hector Boece, which was very kindly brought to my attention by Scottish correspondent Leslie Thomson. The relevant excerpt reads as follows:

...on the summer solstice of the year 1510 some kind of beast the size of a mastiff emerged at dawn from one of those lochs, named Gairloch, having feet like a goose, that without any difficulty knocked down great oak trees with the lashings of its tail. It quickly ran up to the huntsmen and laid low three of them with three blows, the remainder making their escape among the trees. Then, without any hesitation, it immediately returned into the loch. Men think that when this monster appears it portends great evil for the realm, for otherwise it is rarely seen.

Loch Gairloch is a sea loch on Scotland’s northwestern coast; it measures approximately 6 miles long by 1.5 miles wide. As for the creature that emerged from it, I think it safe to assume that its tail’s oak-felling prowess owes more to literary exaggeration than to anatomical accuracy. Conversely, the likening of its feet to those of a goose probably indicated merely that they were webbed. Overall, therefore, the mastiff-sized, web-toed, fleet-footed, quadrupedal water monster of Gairloch does recall the master otter of Glenade Lake, but its taxonomic identity, as with the latter beast’s, remains unresolved.

Furthermore, according to Scottish writer Martin Martin, writing in his most famous book, A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703), on the Inner Hebrides island of Skye (where Martin was born):

…the hunters say there is a big otter above the ordinary size, with a white spot on its breast, and this they call the king of otters; it is rarely seen, and very hard to be killed.

Needless to say, this description readily recalls the so-called 'sea otter' with a white spot on its throat reported from the Priest's Hole seal cave on Ireland's Achill Island by Harris Stone just over a century ago.

Also of relevance here is Wee Oichie or Oichy, the monster of Loch Oich – which is situated directly below the much larger and more famously monster-associated Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands, and is 4 miles long. Wee Oichie traditionally sports a flattened head rather than the familiar equine form often noted for Nessie and various other Scottish loch monsters. Having said that, the head of the very big, black, serpentine beast that rose to the surface one summer's day in 1936 was vaguely dog-like, according to A.J. Robertson who spied it while boating at the loch's southwestern end. Certain other eyewitnesses, moreover, including a former loch keeper at Oich interviewed by investigator J.W. Herries during the 1930s, have likened Wee Oichie to a huge otter.

As a river connects Loch Oich to Loch Ness, some researchers have speculated that perhaps Wee Oichie and Nessie are one and the same (always assuming, of course, that they do actually exist!), merely swimming back and forth from one loch to another via this interconnecting river. Indeed, during the mid-1930s, Herries interviewed three eyewitnesses who claimed to have actually observed such an animal journeying via this exact manner from Ness to Oich.

Also greatly deserving of mention here is that one of Britain's most respected zoologists, the late Dr Maurice Burton, speculated in his book The Elusive Monster (1961) that the existence of an undescribed species of giant otter or otter-like creature might indeed help to explain the Loch Ness monster. Although dismissing most Nessie reports as floating algal mats or misidentified known animals, in his book he considered it possible that a small number of reports genuinely featured an undiscovered long-necked lutrine form:

Those who have made a study of otters in the wild know that they are probably the most elusive animal in the countryside. That, at least, is my experience. An otter may work a river near a village and nobody be aware of its presence...

Let us suppose that the habit and habitat of such a long-necked otter-like animal haunting Loch Ness agree with those of the common otter. Then we have to deal with a most elusive beast, hunting mainly inshore, perhaps basking at times at the water's edge, which for long stretches is out of sight except to the person who, very occasionally, takes the trouble to walk along it. Possibly it may go up the rivers and burns, but wherever it may go there are a thousand and one hiding places where even an animal of these proportions could lie hidden, or could move about without exposing itself unduly, especially if it were mainly nocturnal. If we argue that such an animal would be bound to be seen sooner or later, even in so sparsely populated an area - well, that is the kind of frequency with which it has been reported.

Perhaps Burton's most memorable claim was that if a long-necked giant otter (or otter-like beast) did exist, it should not be looked for in the loch itself but on land close by instead: "...in the marshes or on islands (e.g. Cherry Island [a small island on Loch Ness, at Fort Augustus]), up the burns and rivers or along the shores of the loch, although it may also be seen occasionally in the water". How ironic it would be if generations of Nessie seekers have been looking for the LNM in entirely the wrong habitat!

Is it possible that some form of super-sized otter really did – and even still does – exist in northwestern and western Ireland (and perhaps in northern and northwestern Scotland too), especially in sheltered, little-frequented areas near to the coast, having long since established its place in traditional folklore while eluding formal scientific discovery? Some Eurasian otters do live along coasts, hunting in seawater, and are indeed sometimes dubbed 'sea otters' by local observers, but they also need regular access to freshwater in order to clean their coat. Perhaps down through the years, some such specimens have attained greater sizes than normal, wholly freshwater individuals, their more remote locations protecting them from the unwelcome attention of hunters, and with their impressive appearance but elusive nature having gradually converted them into a magical, folkloric beast, the dobhar-chú.

In any case, from a purely morphological standpoint extra-large otters are by no means restricted to cryptozoology and mythology. In terms of overall size and weight, the biggest species of otter known to exist today is the sea otter Enhydra lutris. Native to the northern and eastern coasts of the North Pacific Ocean, it measures up to 5 ft long and usually weighs up to 100 lb, but a few exceptional specimens weighing up to 119 lb have been confirmed. Although much lighter than the sea otter, the longest known modern-day species of otter is the South American giant otter or saro Pteronura brasiliensis, which can measure up to 6 ft long, weigh up to 71 lb, and is sometimes referred to as a water dog or even a river wolf. Judging from early descriptions of this species, however, it is possible that a few exceptionally large male individuals formerly existed, growing up to as much as 8 ft long, but hunting probably reduced such specimens' occurrence.

Moreover, absolute confirmation that otters can actually attain truly enormous, colossal sizes comes from a gigantic prehistoric species known as the bear otter Enhydriodon dikikae. Named after its huge ursine skull, and inhabiting Ethiopia during the Miocene, this stupendous creature is believed to have weighed around 440 lb. And China's Late Miocene lays claim to a wolf-sized otter called Siamogale melilutra, known from a cranium unearthed at a Yunnan province fossil site and formally described in 2017.

Nevertheless, both of the above-noted living species still share the same overall morphology as other otters (the post-cranial morphology of Enhydriodon and Siamogale are currently unknown), their bodies certainly not resembling a greyhound's, whereas that of the dobhar-chú seemingly does. Consequently, this is a major problem when attempting to reconcile the latter mystery beast with rare sightings of extra-large, coastal-dwelling Eurasian otters.

Judging from the data presented in this article, if the dobhar-chú is a real animal that has been accurately described by eyewitnesses and depicted on the gravestones, then surely it must be taxonomically discrete from the normal Eurasian otter? Moreover, the very sizeable true sea otter Enhydra lutris is an exclusively marine Pacific species that never reaches British or other Atlantic coasts, so this species cannot be involved here either (although, intriguingly, based upon two fossil carnassials uncovered, a related prehistoric species, E. reevei, is known to have existed in East Anglia as recently as the Pleistocene epoch, which ended a mere 11,700 years ago).

Nevertheless, until a specimen is (if ever) obtained, Ireland's mysterious master otter will continue to linger with leprechaun-like evanescence amid the twilight limbo between Celtic folklore and contemporary fact.

UPDATE - 9 December 2020:

Today I received a fascinating, highly informative email from correspondent Richard Ambrose:

On reading your most interesting post regarding this mystery creature, I decided that I would try to find the pub mentioned that held the taxidermied Otter. I decided to look on google maps for the pub, Hyne’s pub is not there however, [but] Hiney’s Bar is!

With this information I looked for them on Facebook and found that they have a page, so I messaged them to see if this was the same place that you had mentioned in your article and, if so; did they still have the Otter? This evening [8 December 2020] I received a message back at 21:12. Yes, it is the correct place and…they still have your Otter (which I have been invited to see should I ever go to Crossmolina).

It's great to know that this potentially significant specimen still exists, and I am exceedingly grateful to Richard for investigating it and informing me of his discovery. It would now be very interesting to determine whether a DNA sample could be obtained from it and, if so, what it revealed... Something for post-Covid 2021, once travel restrictions are over?

This article is a greatly-expanded, updated version of the dobhar-chú account that appeared in my 2003 book The Beasts That Hide From Man, which in turn was an expanded version of my original 1990s dobhar-chú article that appeared in Strange Magazine.