An

adult male specimen of the blue rock thrush Monticola

solitarius (© AquilaGib/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA

3.0 licence)Nowadays, as a result of long experience

in such matters, I am rarely if ever surprised to discover creatures of cryptozoological

interest in ostensibly unlikely sources, but even so I am never less than

interested by them. Such was the case with the subject of this present

ShukerNature blog article, which to my knowledge has never been brought to

cryptozoological attention before.

The tantalizingly short but fascinating

item – from the 1 September 1866 issue in Vol. 2 of a long-discontinued English

periodical entitled Hardwicke's

Science-Gossip – recently came to my attention:

BLUE BIRDS OF GALILEE. – In

the translation of Renan's "Life of Jesus" (cheap edition), there is

mention made at page 74 of "blue birds (at Galilee) so light that they

rest on a blade of grass without bending it." Is there a blue bird in that

region so small as to afford foundation for the statement, and if so, what is

its scientific name? – H.G. [these being the initials of this query's author –

their full name was not given]

Named after its publisher, Robert

Hardwicke, based in London, Hardwicke's

Science-Gossip was published on the first day of each month from 1865 (Vol.

1) to 1893 (Vol. 29), after which it was succeeded by Science-Gossip. Its editors were Mordecai Cubitt Cooke (ed.

1865-1871) and John Ellor Taylor (ed. 1872-1893). Throughout the brief

interchange of correspondence concerning these birds that appeared in this

periodical's pages, and which will be presented in full below, the editor was

Cooke.

A photograph

of Ernest Renan, snapped by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon (public domain)

First of all, however, a word about the

source from which H.B. had quoted the line regarding the blue birds. Published

in 1863, the book in question was a very popular work entitled The Life of Jesus, written by French biblical

scholar Ernest Renan (1823-1892) after having visited Galilee and Jerusalem

during the early 1860s. Hence his account was based upon first-hand knowledge,

not merely upon trawling through the writings of others. Whereas he appeared

distinctly uninspired by Jerusalem's environs, Renan was greatly enamoured by

what he considered to be the natural beauty of Galilee. Here is the full

excerpt from his book regarding its wildlife that contained the line about the

blue birds that had piqued H.B.'s curiosity:

The

saddest country in the world is perhaps the region round about Jerusalem.

Galilee, on the contrary, was a very green, shady, smiling district, the true

home of the Song of Songs, and the songs of the well-beloved. During the two

months of March and April the country forms a carpet of flowers of an

incomparable variety of colors. The animals are small and extremely gentle —

delicate and lively turtle-doves, blue-birds so light that they rest on a blade

of grass without bending it, crested larks which venture almost under the feet

of the traveller, little river tortoises with mild and lively eyes, storks with

grave and modest mien, which, laying aside all timidity, allow man to come

quite near them, and seem almost to invite his approach.

All of the other animal species mentioned

in this excerpt are readily identifiable and familiar sights in Galilee, which

makes the zoologically unrecognizable blue birds all the more perplexing.

Back now, therefore, to H.G.'s plea for

assistance in identifying Renan's feather-light blue mystery mini-birds of

Galilee. It was initially answered, albeit exceedingly succinctly, in the 1

November 1866 issue of Hardwicke's

Science-Gossip by a correspondent signing off with the initials T.G.P.:

BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. – H.G.

inquires as to this bird, mentioned by Renan. The bird that learned author

probably refers to is Cinnaris [sic] osea, the Sun-bird or Honeysucker of

Palestine.

This comment was challenged in the 1

December 1866 issue by the memorably-named Lester Lester, of Monkton Wyld

(nowadays a small settlement within the civil parish of Wootton Fitzpaine, in

the southwest English county of Dorset), who responded somewhat pompously as

follows:

THE BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. –

Will T.G.P. allow one who has lately been reading Tristram's "Land of

Israel" to suggest that the Blue Bird of Galilee is most probably the Blue

Rock-thrush (Petrocincla cyanea), and

not the Sun-bird (Cinnaris [sic] osea)? The habitat of this latter bird

is the Ghor or deep valley of the Jordan and Dead Sea, most especially about

Jericho, and not the rocky hills of Galilee.

T.G.P.'s communication was also responded

to in the 1 January 1867 issue of Vol. 3, this time by none other than the Rev.

Dr H.B. [Henry Baker] Tristram (1822-1906) himself – the English clergyman/scholar/ornithologist

who was the author of the book Land of

Israel that Lester had cited (or, to give it its full, correct title, The Land of Israel: A Journal of Travels in

Palestine, Undertaken With Special Reference to Its Physical Character,

published in 1865).

Rev.

Dr H.B. Tristram, photographed in 1908 (public domain)

However, Rev. Dr Tristram was even more

emphatic than Lester in his dismissal of T.G.P.'s sunbird suggestion:

THE BLUE BIRD OF GALILEE. – I

see that a correspondent in a late number inquired what was "the blue bird

of Galilee." I suppose that fancy may be allowed some scope in the

question, but as a matter of fact there are but two birds to which it can be

applied – the blue Thrush (Petrocincla

cyanea) which is scattered about the Galilean hills and glens in small

numbers all the year round, and the Roller (Coracias

garrula) which is very common over the whole country in summer only. The

Sun-bird (Nectarinia osea) is quite

out of the question. It is not blue, and it barely exists in Galilee; one or

two pairs merely straggling into the neighbourhood of the Lake of Galilee. It

is a bird of the Lower Jordan valley and Dead-Sea basin strictly, and even

there will only be seen by those who look closely for it.

Beneath this communication was a short

square-bracketed addendum provided by the periodical's editor, who at that time

was Cooke. As will be seen below, this addendum consists of a summary of a

presumably longer response by T.G.P. to Tristram's missive (T.G.P.'s full

response was not published, which is a great shame as it would have been most

enlightening to discover what further support he offered for his preferred

sunbird identity). Here it is:

["T.G.P." writes to

us again in support of his opinion that the bird alluded to by Renan, as

"so small and light that it can rest on a blade of grass without bending

it," must be some such small creature as Cinnyris osea.]

And those were the last words on the

subject to appear in Hardwicke's

Science-Gossip. For despite my checking methodically through every

succeeding volume of its entire run (all but Vol. 1 of which can be found

online here, courtesy

of the Biodiversity Heritage Library), no further mention of these enigmatic

birds was found. Nor have I been able to uncover any details regarding them elsewhere.

Moreover, perusing a comprehensive online

checklist of the birds of the Israel/Palestine region provided me with no

additional species worthy of consideration. Consequently, I am focusing my

attention now upon the trio mentioned in the above-quoted correspondence

between T.G.P., Lester, Tristram, and editor Cooke.

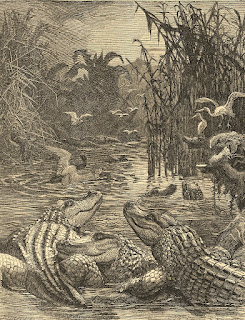

Juvenile

(top), adult female (centre), and adult male (bottom) of the blue rock thrush Monticola solitarius (public domain)

Let’s begin with the blue rock thrush. Nowadays

referred to scientifically as Monticola solitarius

(Petrocincla cyanea as used by

the writers quoted above is now obsolete), this species was traditionally

classified as a thrush, but in more recent times it has been recategorised as a

chat, and thus assigned to the flycatcher family Muscicapidae. Nevertheless, it

retains its long-familiar turdine English name. Moreover, as both its English

and its taxonomic names suggest, this is a montane species, and is certainly

common in the hills and mountains of Galilee. However, despite the confident

assertions by Lester and Tristram that it may well be the identity of Renan's blue

mystery mini-birds encountered by him there, there are two major problems

associated with this identification.

Firstly: only the adult male blue rock

thrush is blue, adult females and juvenile individuals are brown. So unless all

of the birds seen by Renan were males, or specimens of the brown females were

also there but he either didn't notice them or (if he did) he didn't realize that

they belonged to the same species as the blue ones, this weighs heavily against

the blue rock thrush as an identity contender. Secondly, and on the subject of

weighing heavily: the blue rock thrush is the size of a European starling Sturnus vulgaris and weighs up to 2 oz (60

g), with a total length of up to 9 in. Needless to say, therefore, this bird is

far too big to be able to "rest on a blade of grass without bending it".

As noted by Tristram, the European roller

Coracias garrulus is indeed common

throughout the Galilee district in summer, and both sexes sport predominantly blue

plumage. In terms of size, however, this stocky species is even bigger than the

blue rock thrush, being the size of a European jay Garrulus glandarius, boasting a total length of up to 1 ft,

sometimes slightly more, and a weight of up 5.3 oz (150 g). Consequently, it

has even less chance than the blue rock thrush of being able to "rest on a

blade of grass without bending it".

When I first read that memorable descriptive

line from Renan's account of the Galilean mystery blue birds, I thought

straight away that the only birds small enough and light enough in weight to correspond

with it would be hummingbirds – but these of course are all exclusively New

World in occurrence. However, as I then thought, they do have some similarly-sized

Old World ecological counterparts – the nectariniids or sunbirds. Although

taxonomically unrelated, by sharing the hummingbirds' lifestyle the sunbirds through

convergent evolution have come to look and behave very much like them. Could it

be, therefore, that the identity of Renan's feather-light mini-birds is a

sunbird?

Only one species exists in the

Israel/Palestine region of the Middle East – the Palestine sunbird Cinnyris osea (formerly Nectarinia osea). Contrary to Tristram's

claim, this species can appear blue, or at least the breeding male can, which sports

iridescent plumage that shimmers green or blue in sunlight, depending upon the

angle at which it is observed. And it is certainly a much better fit for Renan's

mini-birds than either the blue rock thrush or the roller in terms of its size,

with even the male (larger than the female) not exceeding a total length of 4.75

in, and a weight of 0.3 oz (8 g). One could certainly imagine such a minuscule

bird being able to rest upon a sturdy blade of grass without bending it,

especially with a mountain breeze providing a counterbalance to the sunbird's

weight (such that it is) upon the blade.

This is so obvious that it surprises me

how readily both Lester and (especially) Tristram (given his ornithological

expertise) rejected T.G.P.'s suggestion that the Palestine sunbird was the

likeliest candidate for Renan's mystery mini-birds. (Having said that, Lester was

basing his view upon what he had read in Tristram's book, as opposed to

proffering an entirely independent one of his own.) True, their opposition was

founded largely upon claims that this species simply wasn't common enough in

the Galilean district to be a tenable identity, but they should have conceded

that in terms of size alone, as well as colouring, it was a far more plausible one

than either of their own favoured, but much heavier, candidates.

A breeding

male Palestine sunbird in Israel (© Tom David PikiWiki Israel/Wikipedia – CC BY 2.5 licence)

So how can this ornithological paradox be

reconciled? Might it simply be that the Palestine sunbird is actually more

common in Galilee than attested to by Tristram and Lester? Or perhaps, more

specifically, it is more common there during the months of March and April to

which Renan was alluding in his description of its wildlife? Worth noting,

moreover, is that this species' males do sport their iridescent breeding plumage

during those particular months (click here,

for instance, to see a photograph

of one such specimen exhibiting shimmering blue/green plumage that was snapped during

March 2013 in Israel by Volker Hesse).

Of course, as with the blue rock thrush

contender, if we are to take the Palestine sunbird's identity candidature seriously

we would have to assume that because only its breeding males are blue (or

green, depending upon viewing angle), these were the only individuals to catch

Renan's eye, with the even smaller, dowdy, grey-and-white females overlooked by

him or at least not deemed attractive enough to merit a mention in his

description. To my mind, this is not an unreasonable prospect, as the breeding males

are exceedingly eyecatching, resembling living jewels, and therefore certainly

likely to eclipse the drab females when attracting an observer's attention.

A further possibility is that Renan's

description was overly romantic – a criticism that has been directed at his

writings by various scholars and critics in the past. Perhaps he saw sunbirds somewhere

else in the Israel/Palestine region as opposed to in Galilee, but added them to

his account of Galilee's wildlife as a descriptive flourish – i.e. poetic

licence? Or might he have misremembered where he saw them, erroneously claiming

that they occurred in Galilee when in reality he had seen them elsewhere in

this region? Or could these feather-light fliers have been entirely fictitious,

created by Renan to enhance still further the idyllic image of Galilee conjured

forth by his lyrical narrative?

A

hummingbird hawk moth with slaty-blue body, newly emerged from its chrysalis (© Jean-Pierre

Hamon/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

One final, admittedly remote, but

nonetheless intriguing identity for Renan's mystery mini-birds of Galilee comes

to mind – is it possible that they were not birds at all but were instead a

certain very famous avian impersonator from the insect world? The species that

I have in mind is the hummingbird hawk moth Macroglossum

stellatarium, which so closely resembles a hummingbird not only in size but

also in behaviour that when seen in flight and hovering around flowers,

imbibing nectar using its long slender proboscis, it is often mistaken by

non-naturalists for such a bird.

Furthermore, not only does this species

occur in the Israel/Palestine region and can produce 3-4 broods a year so that

adults are seen all year round, but also its body in particular (and to a lesser

extent its wings) can appear a powdery slaty-blue colour when viewed in

sunlight. And as it is even smaller and lighter in weight than the Palestine

sunbird, it assuredly could "rest on a blade of grass without bending it".

How ironic it would be if both Renan and

the trio of correspondents debating his mystery mini-birds in the pages of Hardwicke's Science-Gossip more than 150

years ago had all been led entirely astray, that the true nature of those tiny

blue blade-resters was not avian at all, but rather that of an incognito

insect, a masquerading moth.

Hummingbird

hawk moth hovering alongside a flower, convergent evolution having transformed this

insect into an extraordinarily precise facsimile of a hummingbird (© Krizzz2020/Wikipedia

– CC BY-SA 4.0 licence)