Of all of my 20 books, none has attracted such acclaim but also such controversy as In Search of Prehistoric Survivors. Next year will mark the 20th anniversary of its original publication in 1995, and having received countless requests from readers over the years for its republication (after having been out of print for a number of years now), I am happy to say that following a protracted period of time doing the rounds of prospective publishers, it was accepted for publication just over a year ago, and I am working upon it with a view to its achieving a timely 2015 reappearance.

Having said that, I am still uncertain as to

whether to prepare a straight reprint of the text but with additional

illustrations (courtesy of the many wonderful ones that have become available

to me since 1995), or whether to update it – and, if I do, how extensive that

update should be. Mindful of the book's enormous scope of cryptids (the only

major group not represented in it are the man-beasts, and that itself was only

for reasons of limited space), a major update would see the book's size grow

dramatically, to the point where it might simply be financially unviable to

produce it. So I need to reflect further upon that. Nevertheless, after having

received so many enquiries, I can definitely confirm that Prehistoric

Survivors will be returning, so watch this space!

Meanwhile, and

after having given the matter much thought, I feel that it may be instructive to

reveal precisely how this particular book of mine came to be, because ever

since it appeared in 1995 there has been a degree of confusion and controversy in

some quarters as to where I stand in relation to its theme and contents. Consequently,

I hope that the following explanation (which I have already outlined privately

to various colleagues down through the years but have never got around to disclosing

publicly before) elucidates all of this satisfactorily.

In many ways,

this book is the most unusual of any of mine, inasmuch as its final, published

form was not how I had originally conceived it at all. Let me explain.

Following the publication in 1991 of my second book, Extraordinary Animals

Worldwide, I was planning a major book on herpetological cryptids –

everything from alleged living dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs, to

mystery lizards of many kinds, giant snakes and crowing serpents, chelonian

cryptids of all shapes and sizes, anomalous amphibians, and even a major section

devoted to the possible origin of and inspiration for the world's plethora of

legendary dragons.

A synopsis of

this proposed book did the rounds of publishers (during which time, incidentally,

my third book, The Lost Ark: New and Rediscovered Animals of the 20th

Century, was published, in late 1993), with Blandford Press being

particularly interested in it (and ultimately publishing it two years later).

Mindful, however, of the enormous worldwide popularity of Steven Spielberg's

blockbuster movie Jurassic Park at that time (the first film had been

released in 1993), they suggested a fundamental change to the contents and slant

of my book. Instead of confining it to herpetological mystery beasts, they

proposed that I should expand its range of subjects to that of cryptids

spanning the entire zoological spectrum, but concentrate exclusively upon those

that have been suggested at one time or another by cryptozoologists to

constitute prehistoric survivors.

It was certainly

a most intriguing brief (albeit very different from my original concept), and

one that I therefore decided to accept, even though – and I must emphasise this

unequivocally here - I did not personally consider it likely that all of those

cryptids truly were prehistoric survivors. But my personal opinion was

irrelevant as far as the book's brief was concerned. What was required was for

me to present for each cryptid a dossier of reports and native traditions, and

then assess them in the context of whichever prehistoric creature(s) it had

been likened to in the cryptozoological literature (with theories not

appertaining to prehistoric survival receiving only minimal treatment, as they

were not the focus of this study). So that is precisely what I did.

Consequently, out went most of the mystery lizards and amphibians as well as

the snakes and also the dragons section, and in came putative mammalian

methuselahs like chalicotheres, thylacoleonids, amphicyonids, and sabre-tooths,

alleged lingering avians like teratorns and Sylviornis, the giant carnivorous

shark megalodon, and even some reputed eurypterid survivors.

A

stunning cover design prepared by cryptozoological artist William Rebsamen for a

proposed updated, retitled edition of In Search of Prehistoric Survivors

(© William Rebsamen)

During the years

that have followed, the concept of prehistoric survivorship – or what British

palaeontologist Dr Darren Naish refers to as the Prehistoric Survivor Paradigm

(PSP) - has received some harsh criticism from cryptozoological sceptics. And

indeed, I am the first to concede that such survival becomes increasingly

untenable the greater the span of time that exists between any modern-day

cryptid and its most recent alleged fossil antecedents (i.e. its so-called

ghost lineage, with the cryptid itself thereby constituting a Lazarus taxon). However,

as my trilogy of books on new and rediscovered animals have disclosed time and

again, some truly extraordinary, spectacular, and entirely unpredictable,

unexpected zoological discoveries have been made in modern times.

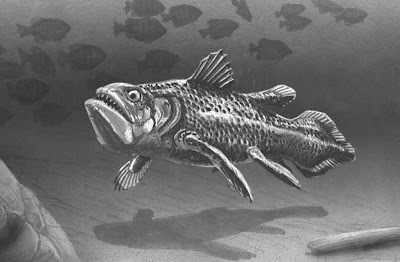

And yes, these do indeed include some bona fide prehistoric survivors, taxa known only from fossils until living representatives were unveiled - e.g. the Chacoan peccary, mountain pygmy possum, Bulmer's fruit bat, kha-nyou, goblin shark, neoglyphean crustaceans, monoplacophoran molluscs, and of course the coelacanth. (And yes again, I am well aware that post-Mesozoic coelacanth fossils are now known, but these were only uncovered and recognised for what they were after the discovery in 1938 of the living Latimeria, when the unexpected resurrection of this ancient lineage of fishes no doubt acted as a significant spur to palaeontologists to seek post-Mesozoic coelacanth fossils that they now knew must exist if suitably preserved, and which would help to close up what could now be seen to be a very extensive and therefore anomalous ghost lineage for these fishes; so at its time of discovery, the modern-day coelacanth was definitely a valid prehistoric survivor.) Hence I remain reluctant to discount PSP out of hand.

And yes, these do indeed include some bona fide prehistoric survivors, taxa known only from fossils until living representatives were unveiled - e.g. the Chacoan peccary, mountain pygmy possum, Bulmer's fruit bat, kha-nyou, goblin shark, neoglyphean crustaceans, monoplacophoran molluscs, and of course the coelacanth. (And yes again, I am well aware that post-Mesozoic coelacanth fossils are now known, but these were only uncovered and recognised for what they were after the discovery in 1938 of the living Latimeria, when the unexpected resurrection of this ancient lineage of fishes no doubt acted as a significant spur to palaeontologists to seek post-Mesozoic coelacanth fossils that they now knew must exist if suitably preserved, and which would help to close up what could now be seen to be a very extensive and therefore anomalous ghost lineage for these fishes; so at its time of discovery, the modern-day coelacanth was definitely a valid prehistoric survivor.) Hence I remain reluctant to discount PSP out of hand.

Having said

that, although I have often been accused of "believing" that a given

cryptid is a particular type of prehistoric survivor, this is simply not true,

for the simple reason that it is impossible to state definitely (although

certain cryptozoologists habitually attempt to do so) what a given cryptid must

be. Without tangible evidence to examine (and I am referring here to physical

remains, not photographic evidence, which can be convincingly faked with

alarming ease nowadays), all that can be done is pass a personal opinion as to how

likely or unlikely a given identity appears to be. However, opinions are not

facts, and should never be put forward, or be mistaken, as such. In short,

therefore, I do not "believe" that any cryptid is any specific

identity – I merely indicate what I personally consider to be likely (or

unlikely) identities for it, nothing more.

Reviving this

book has posed something of a dilemma for me, because doing so meant that its

original brief (and also therefore my own misgivings regarding the plausibility

of prehistoric survival for certain of its cryptids) would remain fundamental

to its raison d'être. The only alternative would be for me to rewrite it

completely, with an entirely altered slant, but the result of that would be not

only a totally different but also a much more extensive book – so extensive, in

fact, that I sincerely doubt

whether it would be financially viable for any publisher to take on. Yet

whatever one's own personal opinion may be concerning prehistoric survival in

any capacity, the wealth of historical reports and cryptozoological coverage

presented in its pages is such that it would be a tragedy for this book

to remain out of print, especially when – as I have been made continually aware

for many years – there is a very considerable demand among readers for it to

reappear.

Consequently, now

that I have outlined here how it came to be and why it is what it is, so that

there can no longer be any confusion or contention regarding it, I am very happy

to engage upon recalling back into existence what many people consider to be my

finest cryptozoological volume. When complete, it may contain various updates

and certainly some major new illustrations, but its basic context and content will

otherwise remain unchanged.

Last, but

definitely not least, I wish to thank most sincerely all of its numerous

supporters for their kind words through all the intervening years, urging me to

resurrect it - just like a veritable prehistoric survivor itself, in fact!

The eyecatching original cover design for In Search of Prehistoric

Survivors, prepared by artist Kevin Maddison and featuring a very striking

Queensland tiger or yarri (albeit one with enlarged canines like placental felids, rather than with enlarged incisors like thylacoleonids!), but which the publisher ultimately rejected in

favour of the plesiosaur flipper cover – ah, well... (© Kevin Maddison)