As recently revealed in Part 1 of this 2-part ShukerNature blog article (click here to access it), the self-styled 'Dr' Albert C. Koch (in reality, he did not possess a doctorate) was one of many 19th-Century Phineas T. Barnum emulators at large in the USA, establishing dime museums filled with a riotous assemblage of factual and phoney specimens from the living and non-living worlds, and, if sufficiently successful, organising nationwide and sometimes even international tours displaying their most famous and fantastic exhibits. In the case of Koch, who was not merely an entrepreneur of this dubious variety but also a passionate amateur palaeontologist and fossil collector, after opening during 1836 one such museum in St Louis, Missouri, he successfully excavated a mastodon skeleton in Missouri's Benton County four years later, but that was far from all.

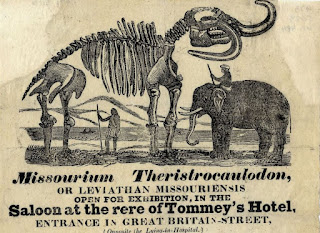

Once Koch had not only assembled this skeleton but also surreptitiously made it much bigger than it actually was by adding extra vertebrae and other bones to it from additional mastodon remains, he dubbed his monstrous multi-mastodon the Missourium, and audaciously claimed that it was nothing less than the fossilised remains of the biblical reptilian sea monster Leviathan. Moreover, after making this phoney mega-beast the central exhibit at his museum for a year, Koch decided in 1841 to sell his museum and go on tour with the Missourium. This he did, but after receiving a very lucrative offer for it from the world-famous palaeontologist Prof. Sir Richard Owen of London's British Museum in 1843 (who readily recognised that the Missourium was a fraudulent composite, not a single creature, but could also see that if dismantled, a complete genuine mastodon skeleton could be reassembled from its components), he promptly sold it to Owen.

However, this meant that Koch now needed a new, equally – if not even more – spectacular exhibit to tour with and earn him further money by drawing in the crowds of visitors anxious to cast their credulous eyes upon it. So, what did he do? He created not one but two gargantuan fossil sea serpents, bigger than any fossil creature ever recorded at that time!

In 1845, an immense skeleton that Koch had recently unearthed in Alabama, and which he claimed to be the near-complete fossilised remains of a prehistoric reptilian sea serpent, was exhibited by him in assembled form, mounted on stilts, in the Apollo Saloon's rooms on New York City’s Broadway.

Measuring at least 114 ft long (but see Koch's own inflated claim below), it consisted of a skull (including a pair of lengthy, tooth-brimming jaws), an exceedingly long, sinuous vertebral column that featured a lengthy curved neck held upright and an even longer horizontally-curved tail, some ribs in the creature's thoracic region, and parts of supposed paddle limbs, He charged interested spectators in America 25 cents to observe his antediluvian marvel, and 1 shilling to spectators in England once he began touring overseas with it.

Despite this specimen looking totally unlike his Missourium, Koch bizarrely stated that it too was the biblical Leviathan! And according to one broadsheet advertisement for its appearance at Niblo's Garden in New York City, he also claimed that when alive it must have measured 30 ft in circumference, and weighed at least 7,500 lb (I've seen one incredible claim that it weighed an outrageous 40,000 lb!).

As with the Missourium, Koch soon prepared a short booklet fully documenting his new reptilian revelation, which was published in 1845. Like before, it sported an unnecessarily lengthy, albeit informative title: Description of the Hydrarchos Harlani (Koch): A Gigantic Fossil Reptile: Lately Discovered by the Author, in the State of Alabama, March 1845 [I've omitted the remainder of its title, which stretched to a further 32 words!]. In it, he introduced his description of the Hydrarchos with the following emphatic pronouncement and dramatic dimensions:

This relic is without exception the largest of all fossil skeletons, found either in the old or new world. Its length being upwards of one hundred and fourteen feet, without estimating any space for the cartilage between the bones, and must, when alive, have measured over one hundred and forty feet, and its circumference probably exceeded thirty feet, reminding us most strikingly, of the various statements made by persons, in regard to having seen large serpents in different parts of the ocean, which were known by the name of Sea Serpents.

As with his Missourium booklet, Koch then went on to provide a lengthy, extremely detailed description containing all manner of unfounded conjectures and suppositions regarding the possible lifestyle and appearance in life of the Hydrarchos (such as sunbathing in rivers; possessing an extremely long neck that it held upwards in an arching curve like a swan to spy unwary prey walking upon the adjoining shore that it could then seize; and cannibalistically devouring younger specimens of its own kind). Ironically, conversely, he also included some accurate accounts of its genuine mammalian characteristics, such as its double-rooted teeth, even at times comparing it directly and favourably with cetaceans (of which Basilosaurus was of course one – see a little later here for Basilosaurus details), only for him then to dismiss them in favour of a reptilian identity for it!

Again as with his Missourium, Koch had given this elongate entity a formal scientific name, which was originally Hydrargos sillimanii, honouring eminent Yale College (now University) naturalist Prof. Benjamin Silliman (1779-1864), who believed in the existence of sea serpents, and had written a fulsome letter of 2 September 1845 to the editors of the New York Express newspaper authenticating Koch's Hydrargos.

Here is what he wrote:

The Skeleton having been found entire, inclosed in limestone, evidently belonged to one individual, and there is the fullest ground for its genuineness. The animal was marine and carnivorous, and at his death was imbedded in that ancient sea where Alabama now is; having myself recently passed 400 miles down the Alabama river, and touched at many places, I have had full opportunity to observe, what many Geologists have affirmed, the marine and oceanic character of the country.

Most observers will probably be struck with the snake-like appearance of the skeleton. It differs, however, most essentially, from any existing or fossil serpent, although it may countenance the popular (and I believe well founded) impression of the existence, in our modern seas, of huge animals, to which the name of sea serpent has been attached.

Notwithstanding Silliman's misplaced faith in its authenticity, however, the true identity – or identities – of Koch's Hydrargos ultimately came to light when one of its numerous visitors, esteemed American anatomist Prof. Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), exposed two major problems with it.

Firstly, its teeth and bones were mammalian, not reptilian, originating from a prehistoric form of very lengthy whale known as Basilosaurus (its reptilian-sounding moniker derives from the fact that when first named by zoologist Dr Richard Harlan (1796-1843), it was mistakenly assumed by him to have been a reptile). Secondly, just like the Missourium, its spinal column was composed of vertebrae obtained from more than one individual specimen (possibly as many as six, in fact, and procured by Koch from several different Alabama locations too), thereby explaining this creature's gigantic size. Indeed, as Basilosaurus attained a total length of 'only' 70 ft or so, Koch's 114-ft Hydrargos was larger than life in every sense!

Once this became known, with the horrid Hydrargos, courtesy of Koch, having duly made a silly man out of Silliman, the latter highly-embarrassed scientist demanded that his name be removed forthwith from the binomial with which Koch had christened his bogus beast. Yet seemingly unfazed by its public unmasking as a fake, Koch simply gave his charlatan sea serpent a new binomial and continued exhibiting it on tour undeterred.

It was now known as Hydrarchos harlani, or simply the Hydrarchos colloquially, its new genus being only a slight modification of the old one, and its new species name, harlani, honouring another scientist. This time it was none other than the afore-mentioned Dr Richard Harlan, who had examined the very first known fossil vertebra of Basilosaurus and had given this archaic whale its misleadingly reptilian genus name in 1835. Moreover, being deceased by now, Harlan was in no position to challenge Koch's usage of his name when rechristening his spoof sea serpent.

In 1848, English palaeontologist Dr Gideon A. Mantell (1790-1852) wrote an excoriating letter to the Illustrated London News denouncing both Koch and his lithic Leviathan, and fully explaining the latter's true nature as a composite Basilosaurus. At much the same time, however, Koch had sold it to Prussia's King Friedrich Wilhelm IV for a lifelong annual pension, so I doubt that Mantell's criticism unduly disturbed him.

In any case, once he had sold his original Hydrarchos specimen, Koch had returned to Alabama and unearthed a second Basilosaurus skeleton in February 1848. From this and other remains, he duly constructed a second Hydrarchos specimen, this one measuring 96 ft long, and then began touring in Europe all over again.

Meanwhile, the new, royal owner of what had previously been Koch's original Hydrarchos gave it to Johannes Müller at Berlin's Royal Anatomical Museum, who, knowing of its true nature, arranged for it to be dismantled, with its components officially relabelled as Basilosaurus remains. Some of these were subsequently sold during the 1850s t0 the Teyler Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, via the fossil auction house Krantz, based in Bonn, Germany (but without their origin in Koch's Hydrarchos being revealed!).

Various other remains from it were donated by Müller to Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde. However, the vast majority were long thought to have been destroyed during World War II, but according to recent ongoing investigations this may not have been the case.

As for Koch's second Hydrarchos: when he finally tired of touring, Koch sold it to the new owner of his erstwhile St Louis museum, who in turn later sold it to a similar establishment in Chicago, Illinois. This was a mini-emporium packed full of curiosities and real specimens intermingled with fake ones, which was owned by Colonel E.L. Wood and duly known as Colonel Wood's Museum.

Here the Hydrarchos was soberly labelled as a specimen of Zeuglodon (a junior synonym of Basilosaurus), rather than as any legendary Leviathan or suchlike. Tragically, however, the entire museum and its contents were destroyed during the great fire that devastated Chicago in 1871.

An inevitable result of his escapades with the Missourium and the two Hydrargos/Hydrarchos specimens was that Koch's name became synonymous with fraud, and by the time of his death in 1867 all claims and finds made by him were routinely dismissed as unreliable by the scientific community. This trend continued for many decades, but based upon some intriguing, corroborating finds in later years by reputable researchers, a number of scientists have reassessed Koch's claims and now believe that some of them, especially ones relating to various human artefacts allegedly found by him in association with fossil mastodons and ground sloths in North America, may have been valid after all.

Even so, it seems highly unlikely that Koch will ever be fully rehabilitated by mainstream science. Thanks to his faked fossil exhibits, he may have acquired fame and fortune, but at the same time he lost the opportunity for scientific recognition that he had always craved – and which he might well have achieved, if only he had presented his notable finds of mastodon and Basilosaurus skeletons in a straightforward, honest manner, rather than wilfully distorting and misrepresenting their nature for purely lucrative, non-scientific purposes. Instead, his name seems forever destined to be irrevocably associated with hoax and fraud.

Finally: It is nothing if not curious that images of Albert C. Koch himself are exceedingly elusive, as I discovered when preparing this 2-part ShukerNature blog article. However, some researchers have claimed that Koch is the figure who is depicted wearing white trousers, and gesticulating towards some newly-unearthed fossil ground sloth remains (a feat that he did indeed accomplish in 1838), within one section of the enormous 348-ft-long painting 'Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Plain', which was produced by artist John J Egan in 1850.

Incidentally, some online commentators regarding this painting, and no doubt influenced by Koch's mastodon excavations, have misidentified the beast remains being gesticulated at in it as those of a mastodon. In reality, however, they are unequivocally from a ground sloth, whose skeleton is visibly very different from that of any mastodon.