I've been promising

ShukerNature readers for almost a year now that I'd write up this fascinating

discovery and post it – so now I have done, and here it is!

A little over 30

years ago, the most famous creatures of cryptozoology were Nessie, the yeti, a

sundry array of sea serpents, and the North American bigfoot. In 1982, however,

following his return to the USA in December 1981 at the end of the second of

two expeditions to the People’s Republic of the Congo (formerly the French

Congo), veteran American cryptozoologist Prof. Roy P. Mackal revealed to an

astonished media and general public that the elusive swamp monster that he had

been searching for in the Congo may conceivably be a living dinosaur! A new

cryptozoological star had been born – an elusive long-necked mystery beast

bearing an extraordinary outward resemblance to a sauropod, and known to the

local Congolese pygmies as the mokele-mbembe. But this wasn't the only

Congolese cryptid that Mackal's team had learnt about during their forays

there. Less familiar but definitely no less interesting was a second major

mystery beast claimed by the pygmies to inhabit that country's vast Likouala

swamplands – a truly extraordinary (and exceedingly formidable) horned creature known

to them as the emela-ntouka, or ‘killer of elephants’.

The size of an

elephant itself, but semi-aquatic, the emela-ntouka is said to have a long

heavy tail, four sturdy legs, and, most notable of all, a very long, sharp horn

borne upon its snout. On first sight, this cryptid sounds like some form of

rhinoceros. However, its long heavy tail differs dramatically from the short,

lightweight version possessed by all known rhino species. So too does its horn,

for whereas those of rhinoceroses are nothing more than masses of compressed

hair, according to native testimony the emela-ntouka’s is said to resemble the

ivory tusk of an elephant. As ivory is only associated with tusks and teeth,

not horns, however, it is probable that if the pygmies' claim about it is

correct, the emela-ntouka's horn is composed of bone.

Its behaviour is

also very distinctive. Although wholly herbivorous, the emela-ntouka is claimed

to be extremely belligerent, so much so that if even something as mighty as an

elephant or buffalo enters a lake in which one of these creatures is residing,

the latter will not hesitate to attack the intruder - stabbing and

disembowelling its hapless victim with its formidable snout-horn.

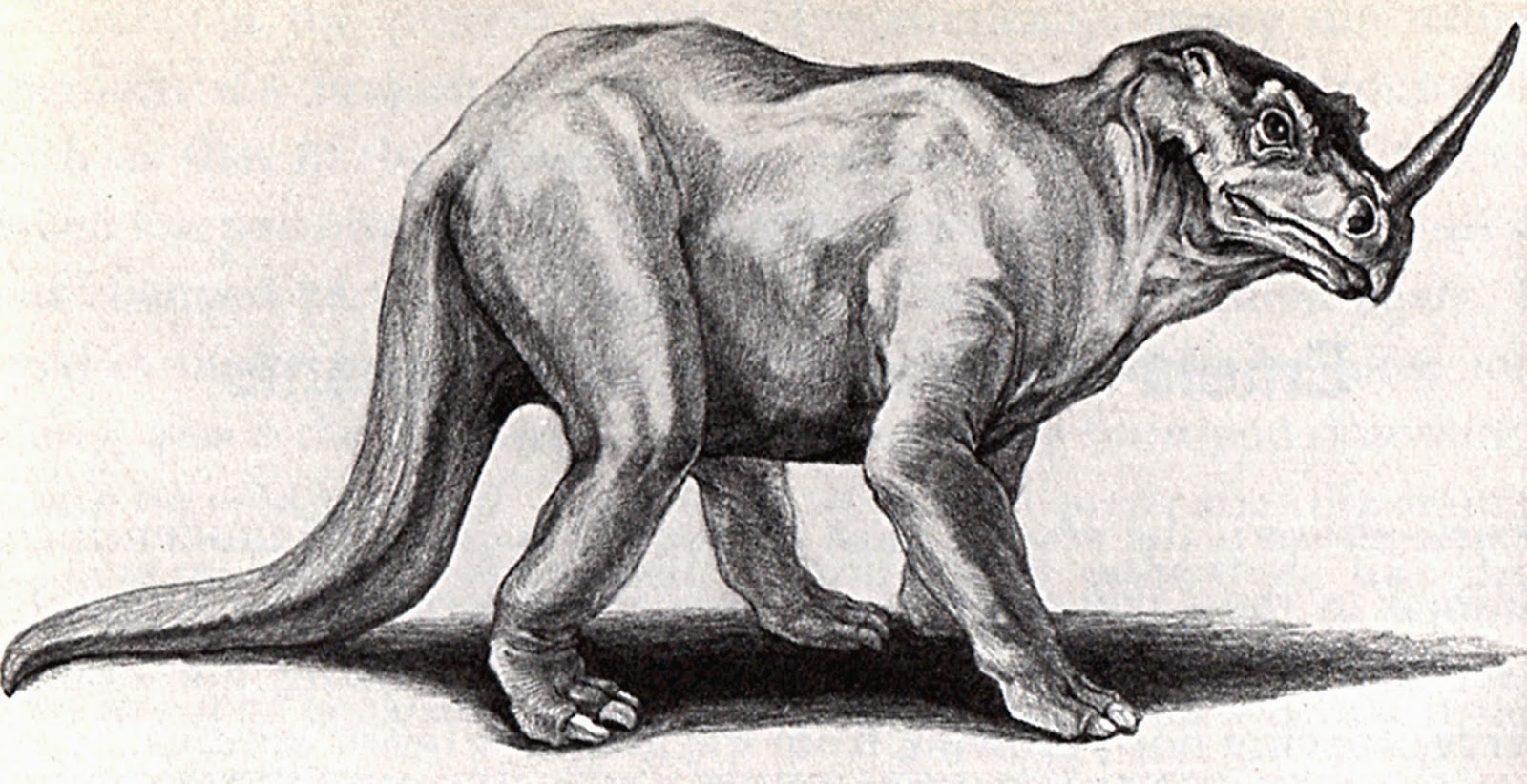

Following his

own investigations of this extraordinary beast, Mackal proposed, albeit

cautiously, that it may actually be a surviving ceratopsian or horned dinosaur

– i.e. belonging to a group of huge herbivorous dinosaurs that included such

prehistoric stalwarts as Triceratops and Styracosaurus. Many

ceratopsians possessed more than one horn, but at least one famous example, Centrosaurus

(formerly called Monoclonius), bore only a single horn, at the end of

its nose – and reconstructions of Centrosaurus certainly recall

descriptions of the emela-ntouka. Moreover, because the horns of ceratopsians

were true horns (composed of bone), not compressed hair, they may well have

resembled ivory, just like the emela-ntouka’s; and all ceratopsians had long

heavy tails, providing yet another match with the emela-ntouka.

Indeed, the only

major discrepancy between the pygmies' description of this cryptid and

palaeontological reconstructions of ceratopsians is that the latter dinosaurs

bore a huge bony frill around their neck, protecting this otherwise-vulnerable

body region from attack by carnivorous dinosaurs, whereas no such frill has

been reported for the emela-ntouka. However, if the latter beast is indeed a

surviving ceratopsian, it is the product of 64 million years of continued

evolution, i.e. from when the most recent fossil ceratopsians died out right up

to the present day - a immense period of time during which evolution could

readily have engineered the reduction or complete elimination of a frill (especially

as such a heavy accoutrement would no longer be needed following the extinction

of the mighty carnivorous dinosaurs).

The emela-ntouka envisaged as a reptile (© Sebastian Tawil)

Equally interesting is that, as with the mokele-mbembe, reports of creatures resembling the emela-ntouka are not confined to the Congo’s Likouala swamplands. The Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) also has its own counterpart, dubbed the irizima, and there are even reports from as far west as Liberia. Moreover, several notable East African lakes, including Lakes Bangweulu, Mweru, and Tanganyika, as well as the Kafue swamps, are said to be inhabited by a very comparable cryptid known as the chipekwe, which kills hippopotamuses with its horn, but does eat them. Occasionally, one of these aggressive animals has itself been killed by native hunters, but, sadly, no remains have ever been made available for scientific analysis. However, the ivory-like horn is said to be highly prized by them, so perhaps there is a chipekwe horn or two preserved in a local chief’s dwelling somewhere in East or Central Africa and awaiting discovery by a sharp-eyed Western explorer, scientist, or missionary?

The emela-ntouka/chipekwe

as portrayed in its jungle swampland domain, complete with hippos! (© Dr Karl

Shuker)

Meanwhile,

French cryptozoologist Michel Ballot has lately found what may be the next best

thing. Since 2004, he has conducted a number of excursions into Cameroon,

seeking evidence for the existence of unknown aquatic beasts. In 2005, during his second

expedition, travelling through a region of northern Cameroon bordering the

Central African Republic, he visited a village where he saw (and purchased) a large, truly

remarkable wooden carving. It depicted in great detail a strange beast with

four sturdy legs, a long heavy tail, and a head whose nose bore a long horn.

Although this carving

doesn’t match any known animal alive today, as can be seen from the photograph

of it reproduced below in this present ShukerNature blog article (and also

click here for Michel's own account of

it, with additional photos) it is a faithful representation of the emela-ntouka.

Photograph

of the more detailed, better-known of the two emela-ntouka carvings encountered

by Michel Ballot in Cameroon

(© Michel Ballot)

Interestingly,

this carving portrays the emela-ntouka with a pair of small frilly ears, almost

like miniature elephant’s ears, a feature not previously reported for this

cryptid but which, if genuinely possessed by it, indicates a mammalian rather

than a reptilian identity. Moreover, in his own account Michel revealed that in 2005 he

had actually found not one but two such carvings, in separate locations and created by separate artists, but identical in appearance. Judging from

the photo below of the second one, however, it is less detailed and less

well-executed than the first, more famous carving.

Photograph

of the second, less-publicised emela-ntouka carving encountered in Cameroon

by Michel Ballot (© Michel Ballot)

Now, in a

ShukerNature world-exclusive, I can reveal a third, independently-obtained but undeniably

corroborative piece of iconographical evidence for the veracity of this

specific morphological identikit relative to the emela-ntouka.

And here is where that

remarkable piece of evidence came to light. Situated in the Central African Republic (CAR), to quote from their website (click here) the Dzanga Sangha Protected Areas or APDS:

"…are

internationally known for their beautiful rainforests, host to a remarkable

diversity of wildlife, comprising western lowland gorillas, forest elephants,

bongo antelopes, forest buffalos and a multitude of bird species. Furthermore,

a rich local culture, comprising the Sangha Sangha fishermen as well as hunting

and gathering BaAka, are present in the area. Apart from conservation and local

development efforts, Dzanga Sangha operates as an eco-tourism and research

centre. A variety of well developed tourism activities and a beautiful hotel

complex, overlooking the Sangha River, are at your disposal.

"Sharing borders with Cameroun and Congo, the Dzanga

Sangha Protected Areas are part of the Trinational Sangha (TNS) complex,

currently in the process to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Roundtrips to

the other National Parks (Lobéké in Cameroun and Nouabalé Ndoki in Congo) can

be organized with ease."

Dzanga Sangha (public domain)

On 8 August 2012, I receieved a fascinating email and attached set of four photographs from Anette Stichnoth of Hannover, Germany. The photographs, taken by a friend of hers from the above-mentioned APDS and named Cem Kok, were of four drawings on display at the first, now-dismantled Dzanga Sangha Exhibition (Cem was currently working on the second one), held in the APDS - with whom Anette was working in the capacity of utilising its exhibition's artworks as designs on souvenirs, such as t-shirts and mugs, that could be sold to APDS visitors in order to raise money for the area's continuing conservation. In relation to this, she asked me if I had any idea what the entities were that the drawings depicted, because she wanted to produce an information card for each one but no-one whom she had previously contacted had been able to identify them.

The artist responsible

for these four drawings was a Frenchman named Jean Claude Thibault, who had produced

them during the early 1990s or late 1980s. He had lived in the Central African

Republic (a former French colony) for a number of years, but could not be

contacted personally concerning his drawings because he had died in Bangui, the

CAR's capital, a couple of years ago.

After examining Thibault's

drawings, it was clear to me that they were nothing if not interesting from a

cryptozoological standpoint. Three of them depicted humanoid or semi-humanoid beings,

and are exclusively documented in a separate ShukerNature blog article (click here) - but the fourth one

was very different, and is reproduced below.

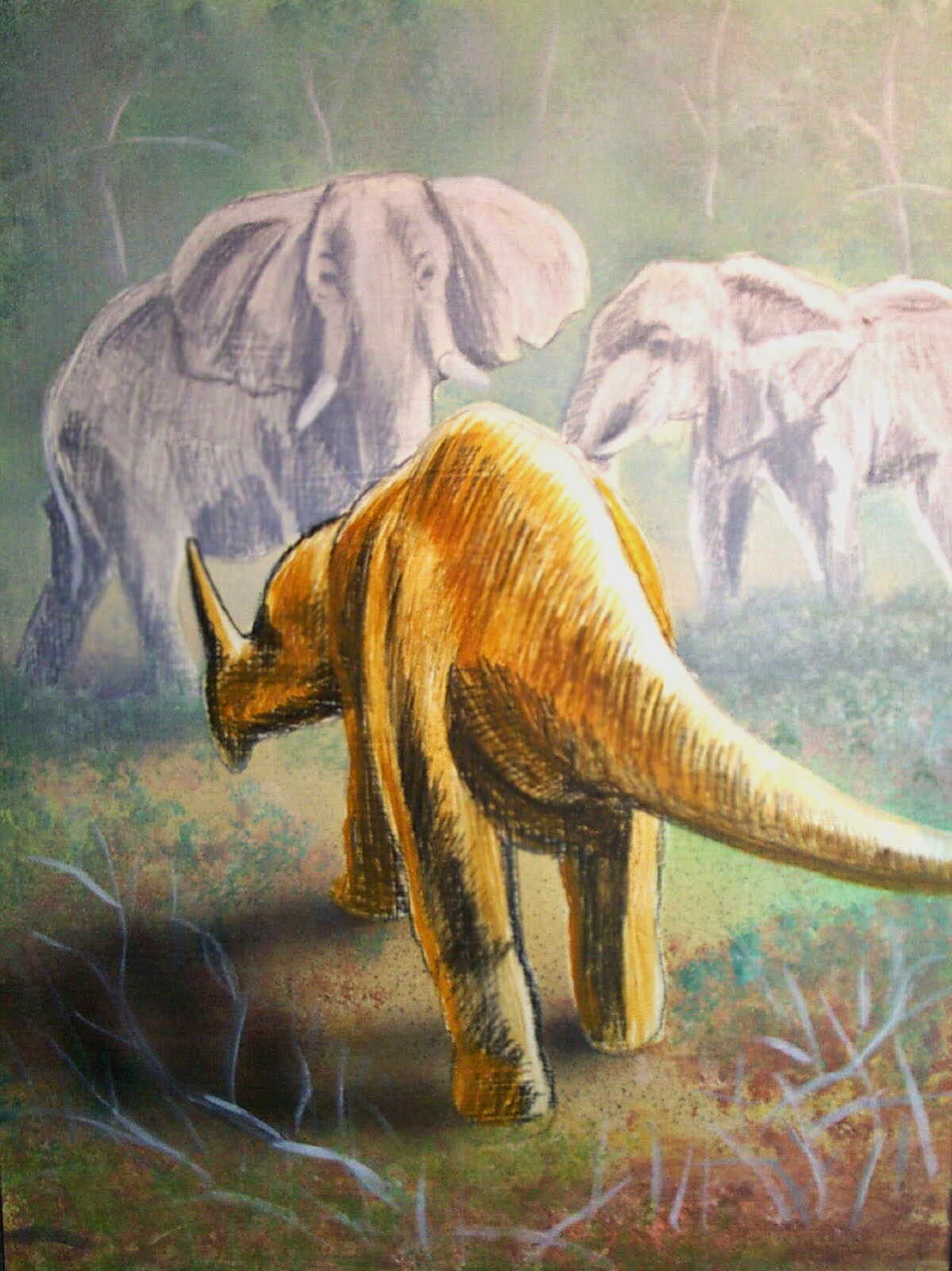

As can be seen, it

portrays one elephant fleeing in the background, plus a second one that has been stabbed in its underside by a horned beast bearing an uncanny resemblance to Michel Ballot's Cameroon-procured emela-ntouka

carvings!

In order to compare those

works of art directly, I have horizontally flipped one of Michel's photographs

of the more detailed of the two Cameroon emela-ntouka carvings, thereby enabling

its orientation to match that of the creature in Thibault's drawing. So here

now are the two images placed alongside one another:

Michel

Ballot's Cameroon-procured emela-ntouka carving (top); and Thibault's Dzangha

Sangha Exhibition drawing, cropped to concentrate upon the horned beast

depicted in it (bottom) (© Michel Ballot/(©

Jean Claude Thibault)

And as can be readily discerned,

there is no doubt whatsoever that these two artworks are indeed depicting the

same species of animal – whatever that may be! Every major morphological

feature - from those strange little frilly ears, and sharp vertical snout-horn,

to the very long, broad, sweeping tail with its distinctive dorsal ridge or

keel, and the relatively short, sturdy, bent legs with well-differentiated

digits - is portrayed in an identical manner by the carving and the drawing.

Even the seemingly stylised, non-differentiated pointed teeth are the same in

both pieces.

Fascinated by this extraordinary correspondence between works of art created in two entirely different countries by artists very unlikely to have ever seen each other's work, I swiftly emailed Anette for additional information. Unfortunately, however, she didn't have anything further of substance to offer me at that time, but promised to contact me again once she had obtained more details – and almost exactly a year later, she did so.

Fascinated by this extraordinary correspondence between works of art created in two entirely different countries by artists very unlikely to have ever seen each other's work, I swiftly emailed Anette for additional information. Unfortunately, however, she didn't have anything further of substance to offer me at that time, but promised to contact me again once she had obtained more details – and almost exactly a year later, she did so.

On 18 August 2013, Anette

emailed me a series of descriptions for the four drawings that she had lately

been given by a CAR local with knowledge of his country's legendary creatures

and entities. The one depicting the

emela-ntouka was labelled as 'Mokele-Mbembe', and the creature was said to inhabit the deepest stretches of the River Ndoki. Referring to it as a mokele-mbembe may seem strange on first sight. However, as I discussed in my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors,

in central Africa (i.e. not just the CAR but also the two Congos,

Cameroon, etc) the long-necked lake-dwelling cryptid (mokele-mbembe) and

the horned lake-dwelling cryptid (emela-ntouka) are often conflated in

local reports, with features of one sometimes being wrongly attributed

to the other, so this is not as surprising as it might otherwise seem.

Due to how astonishingly

similar Thibault's CAR emela-ntouka drawing was to Michel Ballot's Cameroon

emela-ntouka carvings in terms of the creature's morphology, I had initially wondered whether the former had been directly

copied from the latter. Perhaps Thibault had seen online images of the Cameroon

carvings? However, when I learnt that Thibault had produced the drawing a

decade or more before Michel had even encountered the carvings, let alone

photographed them and brought them to public attention by uploading the photos

onto the internet, it is surely evident that they are of independent origin,

neither one influenced by the other. After all, it is highly unlikely that the

Cameroon villagers responsible for the carvings had ever seen Thibault's

drawing, which had only been exhibited publicly

within the CAR, never outside it.

Equally relevant is that although the carved animals and the drawn one possess identical morphologies, the specific poses respectively adopted by them are not the same at all. Both carved animals are standing

stationary, in a neutral behavioural pose, with the head held at a

normal height, the hind limbs close together, and the tail (curving to the right in the

original, non-flipped version of Michel's photograph of the first carving, to the left in the second carving) held laterally for much of its length and very close to the body. The drawn animal,

conversely, is in ferocious attack mode, with its head lowered as it

belligerently drives its horn into the body of its hapless pachyderm victim, its hind legs splayed well apart in

order to brace itself as it performs the powerful thrusting stab with

its horn, and its tail (curving to the left) held out further away from its body in a much wider arc and portrayed throughout its

length from above. In short, the two carved animals and the drawn animal

indisputably portray the same species, but the two carved animals' shared pose is very

different from the drawn animal's - thereby further indicating that the drawing was not copied from or

influenced by the carvings or vice-versa.

Yet as the

carvings and the drawing correspond with one another so closely morphologically speaking, we must

conclude that the image of the emela-ntouka provided by them is an accurate one

– that it really does possess small frilly ears, a vertical snout-horn, bent

legs, and a very broad, lengthy, powerful tail. The ears alone are enough to

demonstrate that it is clearly mammalian in nature (as they are clearly bona fide ears and not, for instance, an abbreviated ceratopsian frill), thereby eliminating a

surviving ceratopsian dinosaur from serious consideration in the future. Yet it

does not compare with any known species of mammal. Indeed, it is not even possible

to allocate this mysterious creature with ease to any existing taxonomic order of

mammals. Having said that, however, the image of it yielded by the carvings and

the drawing does remind me a little of Arsinoitherium zitteli.

Dating from the late

Eocene, this was a massive elephantine horn-bearing species of fossil African

ungulate belonging to the extinct order Embrithopoda. Named after eminent palaeontologist Dr Karl Alfred von Zittel and Queen Arsinoe I, the wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy II (its remains were found in present-day Egypt's Faiyum Oasis), it was believed to have

been aquatic in lifestyle, spending much of its time wading and swimming in rainforest

swamps rather than walking on land, as it was unable to straighten its legs (thus

recalling the emphatically bent legs of the emela-ntouka depicted in the drawing

and carvings). Moreover, it is particularly famous for its pair of truly enormous,

laterally-sited snout horns, composed of bone but hollow and covered in

keratinised skin.

According to their known fossil record, embrithopods officially died out almost 30 million years ago (Arsinoitherium was their last known genus), but could the emela-ntouka possibly be a single-horned, scientifically-undiscovered, modern-day representative? The hefty, lengthy tail, however, poses a notable problem - why would an embrithopod evolve such a decidedly non-ungulate feature? Going full circle, a more conservative alternative would be a species of semi-aquatic water rhinoceros, as first suggested by certain cryptozoologists many years ago. Yet in spite of its single horn, the heavy-tailed creature portrayed by the carvings and drawing bears scant resemblance to any of the diverse array of rhino forms on record from either the present day or prehistoric times.

Skeleton of Arsinoitherium zitteli (© Dr Karl Shuker)

According to their known fossil record, embrithopods officially died out almost 30 million years ago (Arsinoitherium was their last known genus), but could the emela-ntouka possibly be a single-horned, scientifically-undiscovered, modern-day representative? The hefty, lengthy tail, however, poses a notable problem - why would an embrithopod evolve such a decidedly non-ungulate feature? Going full circle, a more conservative alternative would be a species of semi-aquatic water rhinoceros, as first suggested by certain cryptozoologists many years ago. Yet in spite of its single horn, the heavy-tailed creature portrayed by the carvings and drawing bears scant resemblance to any of the diverse array of rhino forms on record from either the present day or prehistoric times.

Currently, therefore, the

emela-ntouka remains an enigma, but at least it is one that now appears to have

a well-defined albeit extremely perplexing morphology.

If you wish to learn

more about or offer assistance to the Dzanga

Sangha Protected Areas (APDS), please visit their website here.

For an extensive

account of the emela-ntouka, chipekwe, and other African counterparts, check

out their coverage in my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (1995).

UPDATE: A SECOND THIBAULT DRAWING OF THE EMELA-NTOUKA

Today, 9 July 2014, I received an extremely interesting email from French cryptozoologist Michel Raynal (thanks Michel!), which provided me not only with additional information concerning the emela-ntouka drawing by Jean Claude Thibault documented here, but also with sight and details of a second one prepared by him, as now revealed.

The drawing already documented here was #12 of twelve Thibault drawings of mythological/legendary entities from the CAR that in 1996 were featured in a special calendar produced by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in the CAR to raise funds for the Doly-Lodge Project in Bayanga, the largest village within the APDS. So this was not a worldwide calendar, but one specifically for the APDS in the CAR. The emela-ntouka drawing subsequently reappeared in 2000 within an article concerning this cryptid published in issue #3 of the Bangui-based anthropological periodical Zo, and written by Alfred J-P. Ndanga, from Bangui University's Department of Anthropology and Palaeontology. Intriguingly, throughout the article Ndanga referred to the creature not as the emela-ntouka but rather as the mokele-mbembe - another instance of conflating these two great water cryptids of central Africa.

As for the second Thibault drawing of the emela-ntouka: this appeared in a Congolese newspaper (date and title currently unknown to me), and is reproduced below (note that once again this cryptid is mis-labelled as a mokele-mbembe):

Today, 9 July 2014, I received an extremely interesting email from French cryptozoologist Michel Raynal (thanks Michel!), which provided me not only with additional information concerning the emela-ntouka drawing by Jean Claude Thibault documented here, but also with sight and details of a second one prepared by him, as now revealed.

The drawing already documented here was #12 of twelve Thibault drawings of mythological/legendary entities from the CAR that in 1996 were featured in a special calendar produced by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in the CAR to raise funds for the Doly-Lodge Project in Bayanga, the largest village within the APDS. So this was not a worldwide calendar, but one specifically for the APDS in the CAR. The emela-ntouka drawing subsequently reappeared in 2000 within an article concerning this cryptid published in issue #3 of the Bangui-based anthropological periodical Zo, and written by Alfred J-P. Ndanga, from Bangui University's Department of Anthropology and Palaeontology. Intriguingly, throughout the article Ndanga referred to the creature not as the emela-ntouka but rather as the mokele-mbembe - another instance of conflating these two great water cryptids of central Africa.

As for the second Thibault drawing of the emela-ntouka: this appeared in a Congolese newspaper (date and title currently unknown to me), and is reproduced below (note that once again this cryptid is mis-labelled as a mokele-mbembe):

The emela-ntouka (© Jean Claude Thibault)