A fruit

bat in flight at Sydney's Royal Botanic

Gardens, Australia (©

Daniel Vianna/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

But when he brushes up against a screen,

We are afraid of what our eyes have seen:

For something is amiss or out of place

When mice with wings can wear a human face.

Theodore Roethke – ‘The

Bat’

The following article

of mine was originally published by Fortean Times in its April 1997

issue (and is reprinted in unchanged form below). Yet despite the initially

encouraging research documented in it, the passage of time following its

publication did not prove kind to the flying primates hypothesis. In more

recent years, sufficient evidence against its veracity as obtained via

comparative DNA analysis with primates, mega-bats, and micro-bats has been

proffered for it to be largely (though not entirely) discounted nowadays by

mainstream workers. (A detailed examination of this evidence is presented online here in British palaeontologist Dr Darren Naish’s Tetrapod Zoology blog.) Nevertheless, even though the notion of fruit bats as our

winged cousins may have been grounded, zoologically speaking it remains of

undeniable historical interest, and was such a charming novelty while it lasted

that I couldn’t resist recalling it on ShukerNature as part of my occasional

'Out of the Archives' series – so here it is.

The fortean literature

contains reports of some exceedingly bizarre entities, but few are any stranger

than the various bat-winged humanoids spasmodically reported from certain

corners of the world. These include such aerial anomalies as the Vietnamese

'bat-woman' soberly described by three American Marines in 1969, the

child-abducting orang bati from the Indonesian island of Seram, and the

letayuschiy chelovek ('flying human') reputedly frequenting the enormous taiga

forest within far-eastern Russia's Primorskiy Kray Territory (click here for further details).

Zoologists have

traditionally averted their eyes from such heretical horrors as these, but in a

classic 'fact is stranger than fiction' scenario, a remarkable evolutionary

theory has lately re-emerged that unites humans and bats in a wholly unexpected

evolutionary manner.

FLYING

FOXES AS WINGED PRIMATES?

As far back as 1910,

W.K. Gregory proposed that bats were closely related to primates - the order of

mammals containing the lemurs, monkeys, apes, and humans. More

recently, Dr Alan Walker revealed that dental features of a supposed fossil

primate christened Propotto leakeyi in 1967 by American zoologist Prof.

George Gaylord Simpson indicated that it was not a primate at all, but actually

a species of fruit bat.

In 1986, however, Queensland University neurobiologist Dr

John D. Pettigrew took this whole issue of apparent bat-primate affinity one

very significant step further, by providing thought-provoking evidence for

believing that the fruit bats may be more than just relatives of primates -

that, in reality, these winged mammals are primates!

All species of bat are

traditionally grouped together within the taxonomic order of mammals known as

Chiroptera. Within that order, however, they are split into two well-defined

suborders. The fruit bats or flying foxes belong to the suborder Megachiroptera

('big bats'), and are therefore colloquially termed mega-bats. All of the other

bats belong to the second suborder, Microchiroptera ('small bats'), and hence

are termed micro-bats.

MACRO-BATS

AND MICRO-BATS – NOT SEEING EYE TO EYE?

As a neurobiologist,

Dr Pettigrew had been interested in determining the degree of similarity

between the nervous systems of mega-bats and micro-bats. In particular, he

sought to compare the pattern of connections linking the retina of the eyes

with a portion of the mid-brain called the tectum, or superior colliculus. He

used specimens of three Pteropus species of fruit bat to represent the

mega-bats. And to obtain the most effective comparison with these, he chose for

his micro-bat representatives some specimens of the Australian ghost bat Macroderma

gigas - one of the world's largest micro-bats. Ideally suited for this

purpose because its visual system is better developed than that of many other

micro-bats, it has large eyes like those of fruit bats, and retinas with a

similar positional arrangement.

Pettigrew's

examination of all of these specimens revealed that the pattern of retinotectal

neural connections was very different between mega-bats and micro-bats, but far

more important was the precise manner in which they differed - providing

a radically new insight not merely into bat evolution but also into the family

tree of humanity.

Reporting his

remarkable findings in 1986, Pettigrew announced that the retinotectal pattern

of connections in fruit bats was very similar to the highly-advanced version

possessed by primates. That fact was made even more astounding by the knowledge

that until this discovery, the primate pattern had been unique. In other words,

it had unambiguously distinguished primates not only from all other mammals

(including the micro-bats) but also from all other vertebrates, i.e. fishes,

amphibians, reptiles, and birds - all of which have a quite different, more

primitive pattern. Suddenly, the fruit bats were in taxonomic turmoil.

NOT

SUCH A FLIGHT OF FANCY?

Until now, the fact

that micro-bats and mega-bats all possessed wings and were capable of

controlled flight had been considered sufficient proof that they were directly

related, because it seemed unlikely that true flight could have evolved in two

totally independent groups of mammals. Gliding, via extensible membranes of

skin, had evolved several times (e.g. in the scaly-tail rodents – click here for some cryptozoological connections); the 'flying' squirrels; three different

groups of 'flying' marsupial phalanger; and the peculiar colugos or 'flying

lemurs' – click here), but this did not

require such anatomical specialisations as the evolution of bona fide, flapping

wings for true flight.

Yet it seemed even

less likely that the advanced retinotectal pathway displayed by primates could

have evolved wholly independently in fruit bats.

In short, by

exhibiting the latter organisation of neural connections, fruit bats now

provided persuasive reasons for zoologists to consider seriously the quite

extraordinary possibility that these winged mammals were not bats at all, in

the sense of being relatives of the micro-bats. Instead, they were nothing less

than flying primates!

Moreover, as Pettigrew

noted in his paper, even the wings of mega-bats and micro-bats are not as

similar as commonly thought. On the contrary, they show certain consistent

skeletal differences, which point once again to separate evolutionary lines.

And even that is not all - thanks to Dermoptera, that tiny taxonomic order of

gliding mammals known somewhat haplessly as the flying lemurs (bearing in mind

that they are not lemurs, and do not fly!) or, more suitably, as the colugos.

For by combining

previously-disclosed similarities in blood proteins between the primates and

the flying lemurs with the structural and neural homology apparent between the

flying lemurs' gliding membranes and the wings of the mega-bats, extra evidence

is obtained for a direct evolutionary link between fruit bats, primates, and

the flying lemurs - thus resurrecting another possibility that had been

suggested by researchers in the past.

FACING

UP TO THE FACTS

One of the most

familiar external differences between mega-bats and micro-bats is the basic

shape of their face.

Whereas the face of

most fruit bats is surprisingly vulpine (hence ‘flying fox’) or even lemurine,

in many micro-bats it is flatter in shape - though in some species, evolution

has superimposed upon this shape all manner of grotesque flaps and projections.

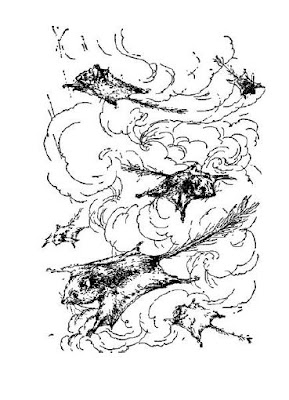

The

uniquely grotesque face of the aptly-named Antillean ghost-faced bat Mormoops

blainvillii, a species of micro-bat native to the West

Indies (public domain)

The lemur-like shape

exhibited by the face of many fruit bats has traditionally been dismissed as evolutionary

convergence, engendered merely by these two mammalian groups' comparable

frugivorous tendencies.

Judging from

Pettigrew's revelations, however, there may now be good reason to believe that

such a similarity is a manifestation of a genuine taxonomic relationship

between lemurs and fruit bats. The faces of the flying lemurs are also very

lemurine (hence their name), which ties in with the above-noted serological

evidence for a direct, flying lemur-primate link.

Thought-provoking

indeed is the evidence for believing that fruit bats are legitimate, albeit

aerially-modified, offshoots from the fundamental family tree of the primates.

As Pettigrew pointed out, it is highly implausible that the reverse theory is

true (i.e. that the fruit bats gave rise to the primates), because fruit bats

seem to be relatively recent species, first evolving long after the primate

link had emerged.

EVIDENCE

FOR AND AGAINST FLYING PRIMATES

Inevitably, no theory

as radical as one implying primate parentage for the fruit bats will remain

unchallenged for very long. In 1992, for instance, molecular biologist Dr Wendy

Bailey and two other colleagues from Detroit's Wayne State University School of

Medicine announced that DNA analysis of the epsilon(e)-globin gene of both

groups of bats, primates, and a selection of other mammals implies that the two

bat groups are more closely related to one another than either is to any other

mammalian group. This finding would therefore seem to support the traditional

bat classification., but as noted by proponents of Pettigrew's ideas, it does

not explain the extraordinary development by fruit bats of the primates'

diagnostic visual pathway. Consequently, this tantalising physiological riddle

currently remains unanswered.

Moreover, in a

comparative immunological study whose results were published during 1994, Drs

Arnd Schreiber, Doris Erker, and Klausdieter Bauer from Heidelberg University showed that proteins

in the blood serum of fruit bats and primates share enough features to suggest

a close taxonomic relationship between these two mammalian groups after all -

thus bringing this continuing controversy full circle.

Many primitive tribes

believe that fruit bats are the spirits of their long-departed ancestors. In

view of the fascinating disclosures reported here, these tribes could be closer

to the truth than they realise!

This ShukerNature blog

article is excerpted from my book Karl Shuker's Alien Zoo – a massive compendium of my Alien Zoo cryptozoological news

reports and my longer Lost Ark cryptozoological

articles that have been published in Fortean Times since the late 1990s.