An adult rufous tinamou, depicted in a beautiful illustration

from 1838 (public domain)

At the turn of

the [19th] century, many tinamous, mainly Pampas hens, were

introduced and raised as game birds in France, England, Germany, and Hungary.

After this initial success, however, all attempts to settle tinamous in Europe

in the wild have failed.

Alexander F.

Skutch – ‘Tinamous’, in Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia, Volume 7, Birds I

To aviculturalists, tinamous are well-known

for being those nondescript, deceptively gallinaceous birds of the Neotropical

Region that are in reality most closely related to certain of the giant,

flightless ratites. Rather less well-known, conversely, is that at one time

they seemed destined to become exotic new members of the English avifauna, as

revealed here.

Tinamous are among the most perplexing and

paradoxical of birds. Comprising some 40-odd species in total, and ranging in

size from 8 in to 21 in, they closely parallel the galliform gamebirds in

outward morphology, with small head and somewhat long, slender neck, plump body

and short tail, sturdy legs, and rounded wings. Admittedly, their beak is

generally rather more slender, elongate, and curved at its tip, and the tail is

often hidden by an uncommonly pronounced development of the rump feathers, but

in overall appearance they could easily be mistaken for a mottle-plumaged

guineafowl, grouse, or quail (depending upon the tinamou species in question).

Even so, it would seem that their

misleadingly gallinaceous morphology is a consequence of convergent evolution

(i.e. tinamous filling the ecological niches in South and Central America

occupied elsewhere by genuine galliform species, but having arisen from a

wholly separate ancestral avian stock). For detailed analyses not only of their

skeletal structure but also of their egg-white proteins and (especially) their

DNA have all indicated that their nearest relatives are actually the

ostrich-like rheas!

Rheas (public domain)

Nonetheless, the tinamous are nowadays

classed within an entire taxonomic order of their own, Tinamiformes, because in

spite of their ratite affinities they have a well-developed keel on their breast-bone

for the attachment of flight muscles, and are indeed able to fly – although

they are not particularly adept aerially. This is probably due to their notably

small heart and lungs, which would seem to be insufficiently robust to power as

energy-expensive an activity as flight. Equally paradoxical is the fact that

although their legs are well-constructed for running, tinamous are not

noticeably successful at this mode of locomotion either, preferring to avoid

danger by freezing motionless with head extended, their cryptic colouration

affording good camouflage amidst their grassland and forest surroundings.

Their outward appearance is not the only

parallel between tinamous and galliform species. On account of the relative

ease with which these intriguing birds can be bagged, in their native

Neotropical homelands tinamous have always been very popular as gamebirds - a

popularity enhanced by the tender and very tasty (if visually odd) nature of

their almost transparent flesh. Accordingly, it could only be a matter of time

before someone contemplated the idea of introducing one or more species of

tinamou into Great Britain as novel additions to its list of gamebirds – a list

already containing the names of several notable outsiders, including the red-legged

partridge Alectoris rufa and the common ring-necked pheasant Phasianus

colchicus.

The concept of establishing naturalised

populations of tinamou in Great Britain was further favoured by the great ease

with which these birds can be raised in captivity, enabling stocks for release

into the wild to be built up very rapidly. So in 1884 the scene was set for the

commencement of this intriguing experiment in avian introduction – the

brainchild of John Bateman, from Brightlingsea, Essex.

The species that Bateman had selected for

this purpose was Rhynchotus rufescens, the rufous tinamou or Pampas hen –

a 16-in-long, grassland-inhabiting form widely distributed in South America,

with a range extending from Brazil and Bolivia to Paraguay, Uruguay, and

Argentina. In April 1883, he had obtained six specimens from a friend, D.

Shennan, of Negrete, Brazil, who had brought them to England from the River

Plate three months earlier. Bateman maintained them in a low, wire-covered

aviary with hay strewn over its floor, sited on one of his homesteads; and by

June, they had laid 30 eggs, most of which successfully hatched - and half of these

survived to adulthood.

In January 1884, naturalist W.B. Tegetmeier

paid Bateman a visit, and became very interested in his plans to release

tinamous in England; on 23 February 1884, The Field published a report

by Tegetmeier regarding this. However, the first release had already occurred

(albeit by accident), because during the summer of 1883 a retriever dog had

broken through the wire-roof of Bateman's tinamou aviary, resulting in the

death of four tinamous, and the escape of seven or eight others onto Bateman's

estate and thence to the Brightlingsea marshes. Only a small number of tinamous

had remained in captivity but these had increased to 13 by the time of Tegetmeier's

visit. As for the escapees, Bateman recognised that they were in grave danger

of being bagged by persons shooting in the area (thereby ending any chance that

they would succeed in establishing a viable population). So in a bid to thwart

this, he issued a handbill, drawing to the attention of local people the basic

appearance and habits of tinamous, and his plans for their naturalisation in

England. The handbill read:

The tinamou,

or, as it is called by the English settlers on the River Plate, "Big

Partridge," is a game bird, sticking almost entirely to the grass land;

size, about that of a hen pheasant; colour when roasted, snowy white

throughout. When flushed, he rises straight into the air with a jump…and then

flies off steadily for about half a mile; he will not rise more than twice. Mr

Bateman proposes, after crossing his stock with the tinamous in the Zoological

Gardens, to turn them out on the Brightlingsea marshes, which are strikingly like

the district whence they came, and he hopes that the gentlemen and sportsmen of

Essex will give the experiment a chance of succeeding, by sparing this bird for

the next few seasons, if they stray, as they are sure to do, into the

neighbouring parishes, as they would supply a great sporting want in the

marshland districts.

To supplement his captive stock, following

Tegetmeier's visit Bateman obtained three more specimens of rufous tinamou from

his friend Shennan, and also purchased three from London Zoo. In April 1885, he

released 11 individuals onto the Brightlingsea marshes; these, together with l4

hatched from eggs, had increased to approximately 50 or 60 birds by September,

according to a second, more extensive report by Tegetmeier (The Field,

l2 September 1885).

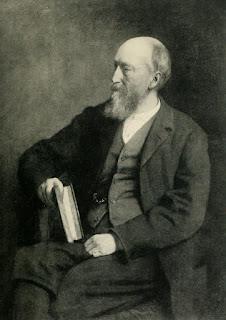

A portrait of

English naturalist W.B. Tegetmeier by Ernest Gustave Girardot (public domain)

Tegetmeier noted that throughout spring and

early summer in Brightlingsea and parts of Thorington, the rufous tinamou's presence

there could be readily confirmed by its very distinctive call, described as a

musical 'ti-a-ú-ú-ú' in the case of the cock bird, and sounding unexpectedly

similar to that of the blackbird Turdus merula. Illustrating this similarity

is an entertaining anecdote contained in a letter to Tegetmeier from Bateman:

Mr Bateman, in

his letter to me, states: “A passing gipsy bird-fancier hailed my keeper's

wife, after listening attentively awhile, with 'That's an uncommon fine

blackbird you've got there, missus,' alluding to the note.

'Yes,' she replied.

'Will you take five bob for him, missus?'

'No; I won't.'

'May I have a look?'

'Yes; ye may.'

'Well I'm blowed!’”

As he well might be, seeing what he regarded as

the note of a blackbird proceeding from a bird as large as a hen pheasant.

Summing up his report of 12 September 1885,

Tegetmeier offered the following words of optimism:

I cannot conclude

without congratulating Mr Bateman on the success of the experiment as far as it

has yet proceeded. So much harm has been done by indiscriminate and thoughtless

acclimatisation, that it is satisfactory to hear that one useful bird has a

chance of being introduced under conditions in which other game birds are not

likely to do well.

Of course, even if the threat to the

tinamous' establishment from shooters could be prevented, there remained the

problem of persecution from four-legged predators – most especially the fox, a

major hunter of tinamous in their native New World homelands. Yet in his second

report, Tegetmeier had dismissed the possibility that foxes would be a danger

to them in England:

. . . there is

no doubt that an English fox would not object to a bird that is as delicate

eating as a landrail [corncrake Crex crex]. The young brood in

Brightlingsea are, however, spared that danger, as the M.F.H. of the Essex and

Suffolk hounds has, with that courtesy which always distinguishes the true

sportsman, granted a dispensation for the season from litters of cubs in the

parish.

Notwithstanding Tegetmeier's optimism, Brightlingsea's Neotropical

newcomers proved to be no match for its indigenous vulpine vanquishers (© Dr

Karl Shuker)

Tragically, however, Tegetmeier's

expectation was not fulfilled; despite all precautions, the foxes triumphed

very shortly afterwards, and the tinamous were exterminated. In less than a

decade, Bateman's hopes for a resident species of tinamou in Britain had been

promisingly born, had temporarily flourished, and had been utterly destroyed. (Moreover,

as noted in this chapter’s opening quote, similar attempts at around the same

time to introduce tinamous elsewhere in Europe also ultimately ended in failure,

no doubt meeting much the same vulpine-vanquishing fate.) By 1896, the entire

episode had been relegated to no more than the briefest of mentions in the

leading ornithological work of that time. Quoting from A Dictionary of Birds

(1894-6) by Prof. Alfred Newton and Hans Gadow:

What would

have been a successful attempt by Mr. John Bateman to naturalise this species, Rhynchotus

rufescens, in England, at Brightlingsea in Essex . . . unfortunately failed

owing to the destruction of the birds by foxes.

A unique chapter in British aviculture was

closed - or was it? In his Introduced Birds of the World (1981), John L.

Long states:

It seems

likely that a number of tinamous, other than the Rufous Tinamou, may have been

introduced into Great Britain, but these attempts appear to be poorly

documented.

The great tinamou Tinamus

major, painted by Joseph Smit in 1895 (public domain)

An event that may have ensued from one such

attempt featured a tinamou far from the Brightlingsea area, but sadly the

precise identity of that bird is very much a matter for conjecture. On 20

January 1900, The Field published the following letter from J.C.

Hawkshaw of Hollycombe, Liphook, Hants:

On Dec. 23

last, while shooting a covert on this estate, a strange bird got up amongst the

pheasants and was shot. On examination it proved to be a great tinamu [sic],

or, as it is sometimes called, martineta. As Christmas was near, I skinned it

myself, with a view of preserving it until I could send it to be set up, and

found it to be in excellent condition, with its crop full of Indian corn, which

it had evidently picked up in the covert, where the pheasants were regularly

fed. The keeper on whose beat it was killed said that he had constantly seen it

feeding with the pheasants. If you would be kind enough to insert the above in

your columns I hope that I may be able to discover whence this stranger had

strayed.

As a footnote to that letter, the editors

of The Field briefly referred to Bateman's experiment at Brightlingsea,

but confessed that they were unaware of any similar trials in Surrey, Sussex,

or Hants (Liphook was sited on the border of those three counties) that might

explain the origin of the specimen reported by Hawkshaw.

Not only was this tinamou's origin a

mystery, so too was its identity. No description of its appearance was given;

the only clues to its species are the two common names, 'great tinamu' and

'martineta', applied to it by Hawkshaw. Ironically, however, these actually

serve only to confuse the matter further, rather than to clarify it. The

problem is that they have been variously applied to at least three completely

different species. Both names have been applied to the rufous tinamou (as in Richard

Lydekker's The Royal Natural History, 1894-96); but 'great tinamou' is

also commonly used in relation to a slightly larger species, Tinamus major

(native to northwestern and central South America, as well as Central America);

and 'martineta' doubles as an alternative name for the elegant tinamou Eudromia

elegans (inhabiting Chile and southern Argentina).

Was Hawkshaw's bird proof, therefore, of

another attempt to introduce the rufous tinamou into Britain; or was it

evidence of a comparable experiment with a different species? Perhaps its

existence in the wild was wholly accidental, totally unplanned – simply a lone

escapee from same aviary. Certainly, tinamous had been maintained in captivity

in Britain, with no attempt made to release them for naturalisation purposes,

by a number of different aviculturalists for many years before this event.

Today, even with such established exotica

as flocks of ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri and golden

pheasants Chrysolophus pictus surviving in widely dispersed areas of the

U.K., it still seems strange to consider that had it not been for an

all-too-formidable onslaught by the foxes of Brightlingsea just over a century ago,

Great Britain may well have become home to an entire extra taxonomic order of

birds – that short-legged relatives of rheas and ostriches would have become a

common sight by now in the fields and marshlands of England, far removed indeed

from their original Neotropical world.

This blog post was excerpted exclusively

for ShukerNature from my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited.