Photograph

of the very first megamouth shark specimen to come to the attention of

scientists, or anyone else for that matter, and revealing very readily why this

remarkable species received its memorable name (© Charles Okamura/Honolulu Advertiser - reproduced here by

kind permission of the Honolulu

Advertiser, on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for

educational/review purposes only)

This is my 700th ShukerNature

blog article – so to celebrate such a momentous occasion, I decided to choose

for its subject something that was big – and not just in physical size either, but

also in zoological significance. Needless to say, the megamouth shark Megachasma pelagios accords perfectly

with both of these requirements, so here it is, making its long-awaited

starring-role debut on ShukerNature.

In terms of precise cryptozoological definitions,

what makes a cryptid a cryptid, i.e. a creature of cryptozoology? There are two

basic criteria. Namely, that it is an animal claimed to exist by and be known

to people sharing its geographical location and habitat (i.e. it is ethno-known),

but which is not officially recognized or formally described by science (i.e.

it is scientifically unknown). Virtually all of the 20th and 21st

Centuries' most spectacular 'new' creatures were once cryptids, i.e. animals

already known locally but hitherto unknown scientifically, such as the okapi,

mountain gorilla, Komodo dragon, coelacanths, Vu Quang ox (saola), and dingiso

tree kangaroo, to name but a few.

Side

view of my megamouth model (© Dr Karl Shuker)

However, there is one very dramatic zoological

discovery that is an equally dramatic exception to this rule – the megamouth

shark. When what proved to be the first of a considerable series of procured

specimens in the years and decades to follow was accidentally captured off Oahu

in the Hawaiian Islands on 15 November 1976 by the anchor of a research vessel

(see later for full details), its remarkable, visually unique species was

entirely new not only to scientists but also to everyone else, even local

fishermen. No-one anywhere had ever seen anything like it before.

In other words, this newly-revealed shark

species was not just scientifically unknown, it was ethno-unknown too. That in

turn means that despite erroneous claims to the contrary as present on many

websites and elsewhere, according to strict cryptozoologial conventions the

megamouth shark was never a cryptid. Its discovery was totally unheralded,

completely unpredicted, and thoroughly anomalous.

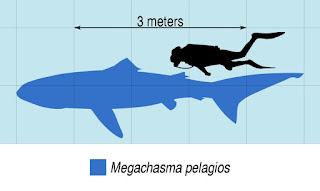

Size

comparison between the megamouth's holotype specimen and a human diver (© Slate

Weasel/Wikipedia, public domain)

Although such a situation is far from

unusual among very small, inconspicuous animals, with creatures as big (one

Taiwanese specimen was apparently 23 ft long) and inordinately distinctive (thanks

to its gargantuan mouth) as the megamouth, conversely, it was (and remains) virtually

unparalleled.

In fact, the only readily comparable

example that comes to mind, and which was also brought to scientific and public

attention for the first time during the mid-1970s, were the 10-ft-tall or so

vertical tube worms with flamboyant crimson tentacles that were discovered

fringing the never-before-visited hydrothermal vents or rifts on the ocean

floor by scientists inside the US research submarine Alvin. Specimens were collected, studied, and their radically new species,

outwardly unlike anything ever encountered before but most closely related to

the pogonophorans or beard worms, was subsequently described and formally named

Riftia pachyptila.

Back to the megamouth, and during the

decades succeeding its 1970s unveiling, there have been just over 100

additional specimens recorded, including some living ones as well as beached

carcases, and from almost every major oceanic region worldwide. This makes it all the

more astonishing that such a sizeable, unmistakable species of shark had

remained wholly undetected by humankind down through all the ages until as late

in time as 1976 – because there certainly did not appear to be a single

recorded instance of anyone anywhere ever having previously reported seeing or

catching something that could conceivably have been a megamouth.

To me, however, this situation has always

seemed to be just too incredible, too implausible, surely, to be true – as a

consequence of which I have spent a lot of time through the years searching online

for any clues that may indicate otherwise, i.e. that might, just might, turn up

some evidence for prior (pre-1976) knowledge of the megamouth's existence, which in turn would mean that it was indeed a cryptid after all. Yet

time and again, my searches were always in vain – it almost seemed as if by

some unexplained biological miracle, on 15 November 1976 the megamouth had

spontaneously generated from seawater! But then, one day, some information

ostensibly of the kind that I had been actively seeking for so long sought me

out instead.

Megamouth

shark illustration (© CSIRO National Fish Collection - Dianne J. Bray, Megachasma in Fishes of Australia/Wikipedia – CC BY 3.0 licence)

On 8 December 2011, responding to a photograph

of the finalized full cover for my forthcoming Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals that I had posted on my Facebook

timeline (or wall, as it was called back then), correspondent H. James Plaskett

added the following short but immensely interesting comment:

The Bermudian

Teddy Tucker told me the Chinese were catching the megamouth shark in the

Pacific in the 1880s.

Needless to say, I found this claim to be

quite electrifying in terms of its potential scientific significance, so I lost

no time in contacting James and eliciting from him some contact details for

Teddy Tucker, after which I emailed him with a request for any additional

details that he could send me. Here, in a ShukerNature world-exclusive, is his

full, never previously-published response, dated 18 January 2012:

I received your inquiry with interest. During

the Beebe Project, we, the National Geographic, University of Maryland and

several organizations interested in the deep ocean, were primarily interested

in the habitats of the water column. We observed many large deep sea

animals that were impossible to accurately identify. These creatures were

seen on deep water cameras deployed to 6,000 feet.

During seventy years of working on and in the

ocean, mostly around Bermuda, in the fall of the year, Oct., Nov. and Dec., the

Cuvier beaked whales feed around the sea mounts, situated on the Bermuda

Rise. The food these whales seemed to prefer is a large mid-water

octopus, how large I do not know, never having seen one intact. I have

collected large pieces of these octopus[es] during the feeding frenzy of these

whales on the surface.

During an expedition to the Pacific, I had the

opportunity to witness a similar feeding frenzy by a similar type of whales

feeding on what appeared to be the same sort of octopus, during this trip two

Japanese scientists on board, told me that the Chinese fished for these large

gelatinous type of octopus in large deep water drift nets, which occasionally

caught large megamouth sharks, which tangled in the nets.

It would seem that the shark and the whale might

feed on this type of octopus, at least they seem to feed in the same

depth. It would be difficult to make a positive identification without

having an actual specimen. It would be reasonable to assume that the

Chinese would have known about the megamouth for many years, as they have been

using deep water drift nets for a long time.

I hope this information is helpful.

Megamouth

shark showing huge mouth, used for filter-feeding – preserved specimen, Japan (©

OpenCage/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.5 licence)

Needless to say, as a dedicated planktivorous

filter-feeder, swimming slowly through the sea with its huge mouth wide open,

filtering water for plankton and jellyfishes, the megamouth shark is unlikely

to feed upon octopuses, gelatinous or otherwise. Conversely, at least 11

megamouth specimens have been recorded off Japan and one off mainland China

since 1976 (plus others off Taiwan), so its modern-day presence in this region

of the Pacific Ocean is fully confirmed. As to whether Chinese fishermen were catching

specimens almost a century prior to 1976, however, this bold but fascinating

claim presently remains unverified.

Yet, undeniably, any such claim also remains

extremely tantalizing, and offers a worthwhile starting point from which to

explore anew the exciting possibility that this most notable non-cryptid may

turn out to have been a bona fide cryptid after all. Having said that, my

periodic peregrinations online in search of megamouth knowledge among bygone

Sinian fishing folk and fishing communities has yet to prove successful – but

there is always tomorrow... Or even yesterday:

Californian newspaper report from 1966 concerning an unidentified shark that may have been a

megamouth? (© Times, San Mateo - reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Also of potential interest here is the above

Californian newspaper report from 15 August 1966, which came to my attention in June 2016, courtesy of fellow British cryptozoological researcher Richard Muirhead. It appeared in The Times (San Mateo).

The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals (© Dr Karl

Shuker/Coachwhip Publications)

Meanwhile, for anyone who has not

previously encountered the engrossing history of the megamouth's modern-day

discovery, here is how I documented it in my Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals, published in 2012:

Most fishermen have a cherished tale or two about 'the big one

that got away', but none can surely compete with the following version - in

which, just for a change, the whopper in question did not get away, much

to the delight of marine biologists throughout the world.

On 15 November

1976, a team of researchers from the Hawaii Laboratory of the Naval Undersea

Center (now known as the Naval Ocean Systems Center) was aboard the research

vessel AFB-14, sited about 26 miles northeast of Kahuku Point, Oahu, in the

Hawaiian Islands. During the course of their work, two large parachutes

employed as sea anchors were dropped overboard, and lowered to a depth of 500

ft. Later that day, when the boat was ready to leave for home, the researchers

hauled the parachutes back up - and found that one of them had drawn up the

greatest ichthyological discovery since the coelacanth! Entangled in the

parachute was a gigantic shark, measuring 14.5 ft in total length, weighing

1653 lb, and differing radically in appearance from all other sharks on record.

Recognising its

worth, the team hauled its mighty body aboard on rollers, and sent it at once

to the Naval Undersea Center's Kaneohe Laboratory, where biologist Lieut. Linda

Hubbell lost no time in contacting the University of Hawaii. Next morning, it

was examined by Dr Leighton R. Taylor, director of the university's Waikiki

Aquarium, after which its body was quick-frozen at a firm of tuna packers, and

retained there until, on 29 November, it was transported (still frozen) to a specially-constructed

preservation tank at the National Maritime Fisheries Service's Kewalo dock

site. It was then thawed and injected with formalin, procedures that marked the

commencement of what was to be an intensive period of study in relation to this

unique specimen - swiftly recognised to represent a dramatically new species

never before brought to the attention of science. The study lasted almost seven

years, and was undertaken jointly by Dr Taylor, Dr Paul Struhsaker of the

Fisheries Service, and shark specialist Dr Leonard Compagno from San Francisco

State University. Preserved, the specimen is now held at Honolulu's Bernice P.

Bishop Museum.

The head of

this strange shark was very large, long, and broad, but not pointed like that

of more typical sharks, whereas its lengthy, cylindrical body tapered markedly

from the broad neck to the slender heterocercal tail (i.e. the tail's upper

lobe was much longer than its lower lobe). Its pectoral fins were also long and

slender, but its pelvic fins and anal fin were very small - smaller than the

first of its two dorsal fins. Identifying it straight away as a male, its

pelvic fins bore a pair of elongate claspers (a male shark's copulatory

organs).

Dorsolateral view of my megamouth

model, showing its huge head and jaws (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The specimen's

huge size made its species, on average, the sixth largest species of modern-day

shark known to science, but even more striking than its overall bulk was its

mouth. Relative to the rest of its body, its mouth was exceedingly large and

wide - a feature that soon earned it in newspaper reports a very fitting

soubriquet - 'megamouth', which became accepted by science as this species'

official English name. In addition to its size, the megamouth's mighty orifice

was distinguished by its thick lips, more than 400 tiny teeth arranged in 236

rows, a very unusual anatomy which meant that its jaws did not lower at the

bottom like those of most sharks but flapped open at the top instead, and -

most startling of all - a silvery mouth lining that glowed in the dark!

Despite initial

speculation that this unexpected last-mentioned feature was due to

light-emitting structures comparable to the bioluminescent organs of many

deepsea fishes and other benthic life, insufficient evidence was obtained from

the study to verify this. Even so, when taken together with the megamouth's

immense size but only tiny, relatively useless teeth, various other anatomical

attributes, plus the great depth at which it was captured, its glowing jaws

indicated that this mysterious marine form was itself a deepsea denizen, whose

lifestyle probably consisted of slow cruises through the inky darkness of the

sea's depths with its huge, glowing jaws held open, to entice inside great

numbers of tiny marine organisms. Thus, the megamouth was a harmless plankton

feeder, a gentle giant.

All of this and

much more was recorded in the paper prepared by Taylor, Struhsaker, and

Compagno, constituting the megamouth's formal scientific description and

published on 6 July 1983. Their study had revealed this mighty creature to be

so unlike all other sharks that they had not merely classed it as a new

species, they had also placed it in an entire genus and family all to

itself. Approving of 'megamouth' as its common name, Taylor and colleagues made

it the basis of this species' scientific name too, christening it Megachasma

pelagios ('great yawning mouth of the open sea') - sole member of the

family Megachasmidae, but most closely allied to the basking shark Cetorhinus

maximus, another plankton feeder.

Attempts to

catch a second megamouth for comparison purposes proved unsuccessful until

November 1984, when another megamouth was caught - but, once again,

completely by accident. This time, a commercial fishing vessel named Helga

took the honours, snaring it unknowingly within a gill net at a depth of only

125 ft, while based close to California's Santa Catalina Island, near Los

Angeles. Needless to say, this priceless specimen was carefully brought ashore,

and was sent at once to the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Tissue samples were taken and stomach contents removed, after which its

14-ft-long body was stored in a frozen state within a temporary case until work

upon a specially-prepared fibreglass display unit was completed, whereupon the

new megamouth was preserved and retained thereafter within its 500 gallons of

70 per cent ethanol.

Preserved megamouth in tank

at the Western Australian Maritime Museum (© Saberwyn/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

The megamouth's

known distribution range expanded dramatically with the third specimen's

discovery. On 18 August 1988, an adult male almost 17 ft long was found washed

up on a beach near Mandurah, a holiday resort south of Perth, Western

Australia. When news of its appearance reached the Western Australian Museum,

ichthyologist Dr Tim Berra (visiting from Ohio State University) and a team of

fish researchers swiftly travelled to the beach to salvage the shark's body. This

was just as well, because some of the resort's residents, not realising its

immense scientific significance, had been attempting (albeit unsuccessfully) to

push it back into the sea!

The scientists

were delighted to find that this latest megamouth was still in good condition,

and it was ultimately preserved and housed in a fibreglass display tank like

that of the Los Angeles specimen. During the tank's construction, it was

retained in a frozen state, enabling the museum's taxidermist to prepare a

plaster cast of its body for exhibition.

On 23 January

1989, a fourth megamouth appeared, stranded dead on the sandy beach of

Hamamatsu City in Japan's Shizuoka Prefecture, yielding the first record of

this species from the western Pacific. An adult male, estimated at over 13 ft

in total length, it attracted the notice of a photographer who took some good

pictures of it that demonstrated beyond any doubt that it really was a

megamouth - all of which was very fortunate, because shortly afterwards, before

there was time to rescue it, this scientifically invaluable specimen was washed

back out to sea and lost. The photos, however, were sent to Dr Kazuhiro Nakaya,

who published them in a short Japanese Journal of Ichthyology report.

Less than six months after this specimen's brief appearance, a second Japanese

megamouth made the headlines, when on 12 June a living specimen was

caught in a net in Suruga Bay. Photographs confirming its identity as a

megamouth were taken, after which it was released unharmed.

The next episode in the megamouth saga however, was truly

spectacular. On 21 October 1990, a sixth specimen turned up, measuring 16 ft 3

in and snared in a drift net off Dana Point, in California. It was towed to

shore by the net's vessel, and was found to be still alive. Marine biologist Dr

Dennis Kelly, from the Orange Coast College, gently examined the huge fish, and

decided that although it would not survive in captivity, it would probably live

if released back into the sea. And so, very carefully, it was set free, and was

filmed underwater as it swam slowly down into the depths from which it had

earlier arisen.

Moreover, capitalising upon this unique opportunity to discover

a little more about its species' lifestyle, a radio transmitter was attached to

its body. This enabled researchers to track it in the sea for the next three

days (after which time the transmitter's batteries ran out), and revealed that

it exhibited vertical migration - moving to the ocean surface only at night,

and descending back into the depths at dawn - which explains how this extremely

large and striking species had escaped scientific detection for so long.

Almost exactly

18 years after the first one was hauled up by a research vessel off Oahu, a

seventh megamouth appeared. This proved to be the first female specimen on

record, and was washed up in Hakata Bay, Kyushu, on 29 November 1994. The third

Japanese megamouth, its body measured 15.5 ft, weighed 0.8 ton, and was

transported to Fukuoka's Marine World Museum, where it was deep-frozen, prior

to permanent preservation.

A hitherto

unsuspected portion of this species' distribution range was revealed on 4 May

1995, when the first megamouth to be recorded from the Atlantic Ocean was

captured by a French tuna fishing vessel, Le Bougainville, in its purse

seine, roughly 40 miles off Dakar, Senegal. This eighth megamouth was a young

male, measuring only 6 ft or so in total length. Regrettably, however, its body

was not preserved.

Megamouth #9

extended its species' known distribution even further, for this specimen,

another young male, approximately 6 ft 3 in long, was procured off southern

Brazil, on 18 September 1995. Its body was retained by the Instituto de Pesca,

in São Paulo, Brazil.

It was the

fourth time for Japan when the megamouth made its next confirmed appearance,

courtesy of only the second known female specimen turning up on 1 May 1997 near

Toba. More than 16 ft long, its carcase was taken to Toba Aquarium.

On the evening

of 20 February 1998, yet another specimen (#11) of this maritime megastar

surfaced - caught by three Filipino fishermen in Macajalar Bay, Cagayan de Oro,

in the Philippines, and estimated to measure around 16 ft. The first on record

from this island group, its taxonomic identity was confirmed on 21 March 1998

by Dr Leonard Compagno. Unfortunately, its body was hacked to pieces after it

had been landed and photographed. Moreover, a female megamouth captured at

Atawa in Mie, Japan, on 23 April 1998 was subsequently discarded.

Megamouth #14,

another female specimen and measuring approximately 17 ft long, was captured in

a drift gillnet roughly 30 miles west of San Diego, California, on 1 October

1999. The third megamouth to be caught off southern California, after being

photographed it was released again, still in good health.

In addition,

Genoa Aquarium worker Pietro Pecchioni claimed in an internet shark discussion

group that he saw and photographed what may have been a living megamouth, being

harassed by three sperm whales near the island of Nain, off northern Sulawesi,

Indonesia, on 30 August 1998. The shark measured 15-18 ft long, and Pecchioni

spied it while in the company of a group of people participating in a WWF

whale-watching programme. When the whales saw the watchers, they came towards

them, then swam away, so the shark survived. At the time of his claim (4

September 1998), Pecchioni's photos had not been developed, but when they were,

the shark’s identity as a megamouth was confirmed (making it megamouth specimen

#13); and the encounter was formally documented by Pecchioni and Milan

University zoologist Dr Carla Benoldi in 1999 on the website of the Florida

Museum of Natural History’s ichthyology department.

Megamouth specimen preserved at Keikyu

Aburatsubo Marine Park, Kanagawa, Japan (© Oos/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

On 19 October 2001, megamouth #15, a male specimen

roughly 18 ft long, was caught alive in a drift gillnet by a commercial

swordfish vessel sited about 42 miles northwest of San Diego. After a United

States National Marine Fisheries Service observer aboard the vessel had

photographed its unexpected catch and had also taken a tissue biopsy from it,

this megamouth was also released in good condition.

Another notable specimen was megamouth #23, which

was washed up on 13 March 2004, onto Gapang Beach in northernmost Sumatra. Only

relatively small, measuring just over 3 ft in length, it was subsequently

frozen at the Lumba Lumba Dive Centre, and following formal examination by

scientists it was deposited at Cibinong Museum. Interestingly, because of

marked differences in shape between this megamouth’s dorsal fins and those of

all previously recorded specimens (and also between its anal fin and those of

previous specimens), when formally documenting it later that year a team of

researchers suggested that these differences may indicate the existence of a

second species of megamouth, but no further evidence for such a situation has

been presented since then.

Megamouth #26 was discovered on 4 November 2004,

stranded but still alive at Namocon Beach, in Tigbauan, Iloilo City, in the

Philippines. An adult female measuring approximately 16.5 ft long and weighing

roughly a ton, this was the third megamouth to have been recorded in the

Philippines, and bore a wound that may have been a spear wound, or possibly a

bite from the cookie cutter shark Isistius brasiliensis. The megamouth

was formally identified the day after its discovery by an official from the

Southeast Asia Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), after which 16 men

carried it to a SEAFDEC aquarium where it lived for a day. It was then

preserved in 10 per cent formalin within a 1-ton fibreglass tank.

As of August

2011, 53 specimens of the megamouth shark have been obtained or conclusively

sighted [but as of August 2020 this number has increased to just over 100]. The

three most recent ones are: #51, a specimen of unknown sex caught off eastern

Taiwan on 19 June 2010, but later cut up for meat that was sold at a local

market, with only a jaw retained; #52, a dead juvenile male specimen captured

by fishermen close to the western Baja California peninsula of Mexico on 12

June 2011; and #53, an individual of unspecified sex but measuring

approximately 10 ft long that was recorded from Japan’s Kanagawa Prefecture on

1 July 2011. A comprehensive listing of these, together with pertinent details

of their respective discoveries, plus a detailed bibliography of sources, can

be accessed on a number of online websites.

Finally: an

intriguing footnote (fin-note?) to the megamouth history is that this species'

own discovery set the scene for a remarkable parasitological parallel. During

the study of the very first megamouth specimen, an extremely strange form of

tapeworm was found inside its intestine. When closely examined, this peculiar

parasite proved to be not just a new species (later named Mixodigma

leptaleum), but one so different from all others that it required a

completely new genus and family - exactly like its megamouth host!

Since I wrote that account, fossilised

teeth from what are believed by some palaeontologists to have been two ancestral

megamouth species (M. alisonae and M. applegatei) dating back to the late

Eocene/early Miocene have been described. If correctly identified, these

readily prove – if proof were needed! – that the present-day megamouth species M. pelagios did not generate spontaneously

in 1976 after all!

On the contrary, this amazing creature's

existence and evolution can be traced back millions of years – making it even

more astonishing, vertical migration notwithstanding, that it successfully

eluded discovery by science and the public alike until less than half a century

ago (unless there really are some Sinian insinuations to the contrary still to

be uncovered?).

Miniature Sheet depicting the

megamouth, issued by the Comoros in 2010, from my own stamp collection (©

Comoros Philatelic Bureau – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair

Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

In view of this, I can't think of a

better way in which to bring ShukerNature's mega-monograph of the megamouth to

a fitting close than by reflecting upon the following quote from the

previously-mentioned ichthyological expert Dr Leighton R. Taylor, as contained

in a published interview with the Waikiki

Beach Press newspaper:

The discovery of megamouth does one thing. It

reaffirms science's suspicion that there are still all kinds of things - very

large things - living in our oceans that we still don't know about. And that's

very exciting.

It is indeed!

UPDATE, 10 May 2023 - I've learned today from crypto-colleague Tyler Greenfield that the 1966 mystery shark was subsequently confirmed to be a sleeper shark (family Somniosidae). Photographs of it, taken by John Isaacs/Scripps Institute, were published in the 1971 book The Face of the Deep, authored by Bruce C. Heezen and Charles D. Hollister. Thanks Tyler!

PS – If you would like to see footage of a living megamouth

shark, be sure to click here to see

one that was filmed off Japan earlier this year, 2020; plus here and here to see others as

featured in a couple of online mini-megamouth documentaries.

Present

but uncredited on several websites online - how a genuine photograph of a

beached megamouth shark has been converted by hoaxer(s) unknown into a fake

photograph of a beached plesiosaur (© owner/s unknown to me, reproduced here on

a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)