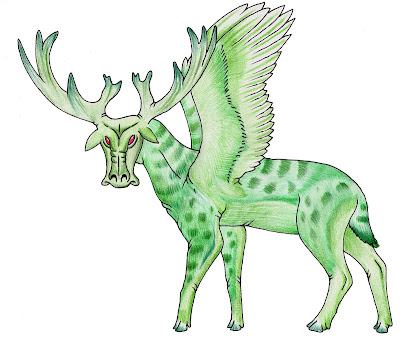

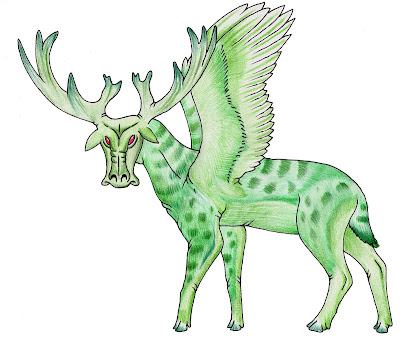

A peryton ((c) Pat Burroughs)

A peryton ((c) Pat Burroughs)

Evil can assume many guises, and not all of them are ugly or repellent. On the contrary, in the shadowy, sequestered realm of legendary non-human entities that were once widely believed to be real, there are numerous examples of alluring, deceiving, malign beasts of murderous beauty and deadly innocence, as epitomised by the following lesser-known but invariably lethal monsters of hoof and antler.

According to fable, the perytons were once a mighty race of noble beasts that inhabited the mountainous peaks of Atlantis. Here they lived in peace with all living things, until humanity’s evil gradually spread like a vile cancer across the entire expanse of this vast and glorious island continent. Eventually even the gods despaired of the Atlanteans, whose skills in the dark arts threatened the existence of the entire world, and so it was decided that Atlantis and all of its heathen practitioners must be destroyed. The gods duly besieged the continent with earthquakes, tidal waves, plagues, and, most catastrophic of all, an immense volcanic eruption that decimated Atlantis and finally sank this once-illustrious land beneath the waves, staining with blood and ash the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean.

Just before it vanished forever, however, the perytons were able to flee, flying far from their doomed homeland to find sanctuary amid the high peaks of Greece and also, on the far side of the Mediterranean, those of Carthage and elsewhere in North Africa. Here these formidable creatures vowed to take relentless, bloody revenge on all mankind for the annihilation of their idyllic Atlantean domain. If a peryton saw an opportunity to kill a human, it would take it unhesitatingly, and would be assured of success on account of its invulnerability to all weapons created by men. Moreover, once a peryton had killed a human, it would gain a prize valued beyond all others by these creatures. Fortunately for humanity, however, each peryton could only kill a single human with impunity – after that, its invulnerability was lost and it too could therefore be slain. But what were perytons – what did they look like? As will be revealed here, a peryton was unlike anything else that had ever existed, and so could not be mistaken for anything else – except, that is, when it resorted to a unique form of dark, fatal trickery.

After their enforced exile from Atlantis, a mighty flock of these lethal beasts had attacked a mighty Roman fleet led by the celebrated general Scipio as its flotilla of four-score war ships and countless accompanying transport vessels journeyed across the Mediterranean to sack Carthage, and the perytons had inflicted terrible carnage before they were eventually repelled with unparalleled success by Scipio’s formidable troops. Since then, the perytons had remained concealed and aloof from humans in their mountainous retreats, humiliated by their unwonted defeat and gradually diminishing in numbers as the centuries slipped by, until they had become largely forgotten by the world beyond their remote peaks, relegated like the harpies, the minotaur, and other monstrosities of long ago to the neverland of nightmare. But very occasionally, a nightmare can become a reality...

An interesting variation - Una Woodruff's spectacular painting of a blue, horned peryton in her superb book Inventorum Natura (1979), which attempts to recreate the lost journal of Pliny the Elder ((c) Una Woodruff)

An interesting variation - Una Woodruff's spectacular painting of a blue, horned peryton in her superb book Inventorum Natura (1979), which attempts to recreate the lost journal of Pliny the Elder ((c) Una Woodruff)

It had been a weary journey for the once-valiant, now-broken knight crusader, returning to his Greek homeland not in jubilation but rather in desolation for all of his dead and dying comrades, and accompanied only by his faithful squire. During the past weeks, they had ridden far indeed from the hideous scenes of bloodshed and mayhem that they had experienced for so long but had now left behind amid the corpse-strewn battlefields of the Holy Crusade. Yet those same scenes, and even worse ones, still rampaged with unending fervour in their shattered minds and within every nightmare that their fevered, ever-disturbed bouts of sleep generated.

And now, scarcely had they returned home before their friends, neighbours, and other townsfolk had beseeched the knight to seek out and vanquish a mysterious monster that had supposedly been glimpsed from time to time amid the dark, forbidding mountains close by during his absence. No-one was certain of the beast’s appearance, but all were certain that it existed. And so, armed with lance and shield, the knight, accompanied once more by his trusty squire, set off along the lonely path that wound its way up through the forests towards the plenitude of caves and caverns that pitted the mountainsides like pockmarks on the face of a titan.

Who knows what the knight would face if he did indeed encounter a monster there? Having said that, the dread beasts of ancient Greek tradition were just stories and legends, weren’t they? And even if they had been real once upon a time, surely that time was long since past now? Then again, certain of those entities were said to be immortal, such as the twin sisters of Medusa - she of the petrifying stare and snake-locked hair. Could that be what lay ahead, lurking in wait for him – the last of the gorgons? Or might it instead be a conflagrating multi-headed dragon, or even a hag-faced harpy with foul wings and fouler breath, ready to tear him apart with her crooked beak and talons of steel?

At least such thoughts, unpleasant though they unquestionably were, had succeeded in supplanting those previously tenacious images of the battlefield’s carnage. So, in a strange way, the knight’s mood had actually begun to lighten and lift as he and his squire continued their cautious ascent along the mountain path.

By now, their little town had been left far behind, so far that it could no longer be clearly discerned even from their lofty vantage point. And ahead? A grey vista of cliff faces, cloud-embraced peaks, and shadowy cave mouths surrounded them. The monster, if it did indeed exist, could be anywhere – so where should they begin their search?

As if in answer to their unspoken question, a cry suddenly echoed forth from the bowels of a tall but fairly narrow cave to their left, whose entrance was at the end of a high corridor-like passage through some rocks. The knight and his squire paused, listening closely, and the cry came again. It was a human voice, surely, a man’s voice, calling out for help, pleading to be rescued before the monster appeared!

Armed and ready for mortal combat ((c) Dr Karl Shuker)

Armed and ready for mortal combat ((c) Dr Karl Shuker)

The knight and squire rode closer, but the knight was well aware from the ancient legends and superstitious folklore of his land that many monsters had successfully lured men and women to their doom by skilfully imitating a human voice. And so the knight called out, in the direction of the passage, for whoever was crying forth to show himself, and thus prove that he was human.

For a few moments there was silence, then came the sound of something moving slowly down the passage, until a shadow fell upon the exposed rock face at the passage’s entrance. It was the shadow of a man, a little stooped, perhaps, as if elderly or ailing, but undeniably human.

When the knight saw this, he and his squire rode up, approaching the entrance – but just before they reached it, the knight’s horse gave a wild neigh of fear and tried to swerve away, shaking in terror. Yet all that could be seen was the lone shadow of the man.

The knight looked away from the entrance as he sought to gain control of his panicking steed, which by now was thrashing its head from side to side and frothing madly in uncontrollable fright. And so it was his squire that saw who – or, rather, what – emerged from the passage to confront them.

Hearing his squire’s shrieks of horror, the knight turned back to look at the cave, and there, rearing up on its hind legs, was a beast that even in his wildest nightmares he had never thought of as anything other than fable and lurid fantasy. Yet here it was right now – only too real, and only too ready to kill him. It was a peryton!

On first sight it resembled a huge stag, sporting a pair of magnificent branching antlers, but as it reared directly in front of him, flailing its gleaming hooves, an enormous pair of plumed wings, sprouting from its shoulders, spread forth like the very pinions of Pegasus. And instead of fur, this unnatural creature was clothed in dark-green plumage, like some monstrous miscegenation of deer and tropical bird.

But most bizarre and uncanny of all was its shadow, which confirmed the creature’s identity as a bona fide peryton, albeit quite possibly the very last of its kind remaining on Earth. For there, cast upon the rock face as before, was not the shadow of a winged, feathered deer but instead the perfect facsimile of a human shadow – that which had fooled and lured the knight and his squire to the lair of this terrifying relic from an earlier world, whose eyes of fire and savage mien revealed only too readily its murderous intent.

For if a peryton should succeed in killing a human, not only would it rid the world of yet another member of the race that it would forever blame for the destruction of its own species’ blessed homeland, it would also gain something uniquely precious for itself – its own true shadow, the shadow of a peryton. Even so, upon killing a human a peryton would lose its resistance to man-made weapons, but that was a small price to pay – and it was evident that the peryton confronting the knight and his squire was more than willing to pay it.

All of this the knight knew only too well, as did his squire. In short, to vanquish this monster from a vanished land one of them must meet a grisly end - gored to death by the peryton’s antlers, then ripped asunder and trampled into the earth by its razor-sharp hooves. Undaunted, however, the knight swiftly dismounted from his nervy steed, and with shield and lance at the ready he slowly advanced on foot, signalling to his squire to stay back and hold his horse fast, in case he should need it. Perhaps the peryton possessed some vulnerable spot not spoken of in the old stories and myths – if so, he would find it, or die in the attempt.

Lowering its great head, the peryton eyed the knight with vibrant hatred, then charged toward him like a bull before a matador, but the knight fended it off with his burnished shield, rather than with a cloak of scarlet, which directed beams of sunlight into its eyes, temporarily blinding the raging creature and granting the knight precious moments in which to scrutinise it at close range in the hope of spying some weakness, some flaw, that might engineer its destruction.

But there was none.

If only he had known before ascending the mountain that the monster he would face there would be a peryton, he could have prepared himself accordingly, by abandoning human weapons and utilising the natural elements instead, against which the peryton had no invincibility. Fire or water to drive the creature back into its cavernous hideaway, and then perhaps the triggering of an avalanche in this unstable, rocky terrain, in order to imprison it inside the cave forever with a barrage of falling boulders sealing the entrance. That strategy might have succeeded, but now, now it was all too late.

A further representation of a peryton ((c) Tim Morris)

A further representation of a peryton ((c) Tim Morris)

Time and again the peryton charged, and each time the knight deflected it with his shield, in a chilling dance of would-be death, but he was tiring. Months of fighting in the Crusade and weathering the most traumatic and draining of living conditions had severely weakened him – a lengthy respite from all forms of conflict was what he needed to recuperate, not a mortal battle with a monster of the peryton’s stature and power.

Suddenly, as he attempted yet another feint of the peryton’s antlers with his shield, the knight lost his footing, dropping his lance onto the ground as he stumbled backwards, falling awkwardly against the trunk of a tree. And in those few seconds while he struggled with the weight of his armour to stand upright, the peryton saw its opportunity and charged directly at him, hitting him with such force that his armour’s breastplate split down the centre, exposing his chest to the sharp tines of the peryton’s antlers. They pierced his torso with such force, impaling him upon themselves, that the peryton was momentarily pinned by its own antlers into the tree’s hard trunk, before, with a mighty heaving movement, it hauled them back out.

Freed from their deadly tines, the body of the dying knight slumped to the ground. His head turned one last time, to look at his squire, who stood transfixed with horror and rage at his master’s fate, and he smiled gently. By meeting his own demise at the antlers of the peryton, he had saved his squire, who had also been his friend for more years than either of them could remember, and so there was no shame in his defeat, only quiet thankfulness. The knight closed his eyes, and then, finally at peace with a world in which he had lately seen so much turmoil and terror, he died.

And at that same moment, the peryton let out a roar of triumphant joy, for as it gazed at its shadow against the rock face, the shadow began to shiver and tremble. Its outline became blurred and its form extended and expanded, rapidly transforming – until, within just a few moments, the shadow of a man had metamorphosed into the shadow of a peryton.

Exultant, the peryton opened its great wings, ready to depart elsewhere, to seek out a more remote land where, now that it was no longer impervious to human weapons, it could live on in safety and anonymity. But still it gazed at its new shadow, delighting in its appearance after dreaming of and waiting so long for this supreme moment, this ultimate triumph.

And so it never saw the squire creep across the ground and seize the lance of his dead master, and it never saw the squire take the lance in his right hand, pull back his arm, and take deadly aim with the lance at the peryton’s own chest. It never heard the squire’s muttered prayer to the God who had kept him and his master safe during the horrors of the Crusade, and it never felt the strong breeze that seemed to blow in from nowhere, lifting, bearing, and empowering the lance as the squire hurled it with all his might at the peryton’s chest.

The squire’s aim, guided surely by the divine breeze, found its mark – spearing the shocked peryton through the very centre of its beating heart, skewering it like a moth impaled upon a lepidopterist’s pin. Open-mouthed, the peryton turned its head to meet the flushed face of the squire, and as it sank to its knees, the last vision that the slain peryton saw was the squire’s own eyes, suffused with the raging, glowing fire of retribution as he watched with grim satisfaction the peryton’s death. He had avenged his master, his friend, and as he knelt before the knight’s body in thankful prayer for his success in doing so, the breeze momentarily caressed his cheek before disappearing as swiftly and mysteriously as it had arisen - leaving the squire in silent vigil.

Here in the mountains, he would remain, guarding the knight’s body throughout the oncoming hours of nightfall and darkness in a lone vigil, until the dawn’s first light, when he would then descend the winding path leading to their little town and seek help there in transporting with all due reverence and care his master back home, for the last time.

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges (featuring Peter Goodfellow's fantastic front cover painting)

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges (featuring Peter Goodfellow's fantastic front cover painting)

According to Jorge Luis Borges’s classic work The Book of Imaginary Beings (1969), which is often said to be the first modern-day book to document perytons, all of the information concerning these creatures that is known today is derived from a 16th-Century Fez rabbi’s historical treatise, or, rather, from the now-lost work of an unnamed scholar from ancient Greece that the rabbi had quoted in his own treatise. Borges asserted that until the outbreak of World War II, the single known copy of that treatise was held in the University of Dresden’s library. Tragically, however, perhaps as a result of the severe bombing of this German city by the Allies, or of the Nazis’ own notorious book-burning sessions, by the end of the war the rabbi’s unique manuscript had gone missing, and has never been found again – nor, indeed, has any additional copy of it.

Having said that, some authorities have suggested that Borges invented the entire peryton myth himself (including his assertions concerning the supposed erstwhile existence of the rabbi’s treatise, as well as another claim by him, that a sibyl had foretold – wrongly – that a phalanx of perytons would destroy Rome); and that, in fact, there was no peryton lore or tradition whatsoever prior to his book. However, there are several notable sources of winged deer information and portrayals (especially in heraldry, Western architecture and sculpture, early Hindu art, occultism, and even antique jewellery) that very considerably pre-date the publication of Borges’s book. Whether they are meant to represent genuine perytons is unclear, but they certainly exist.

As noted, for instance, in K. Krishna Murthy’s book Mythical Animals in Indian Art:

"The winged deer or stag...gets its sculptural representation more than once in the early Indian sculptures. However, the best specimens of the winged stags can be seen in the reliefs of Sanchi. A clear example of two winged stags sitting back to back occurs on the front of the northern Torana gateways."

Nor should we – or, indeed, could we – overlook the visual extravaganza that constitutes the glorious fountain replete with golden statues of winged deer that forms part of the huge garden around La Granja – the sumptuous palace in Segovia, Spain, that was built in 1721-24 by Philip V.

Perhaps the most distinctive British example is the ornate statue of a winged stag sitting upright on its haunches that is just one of many large, intricately-detailed sculptures of fantastic beings forming part of the elaborate fountain in the courtyard of West Lothian’s Linlithgow Palace. Nowadays, this Scottish palace is largely in ruins internally, but the fountain still survives and dates back to the reign of King James V (1512-1542).

Statue of a green winged stag at Linlithgow Palace ((c) amyhooton/deviantart)

Statue of a green winged stag at Linlithgow Palace ((c) amyhooton/deviantart)

Although the fountain’s winged stag statue may simply represent a composite heraldic beast, it is interesting to note that algal growth has turned it green in colour – the same colour that the perytons were said to be. Just a coincidence? Perhaps the next time that anyone visits this fountain, they should take note of the shadow cast by the winged stag’s green statue. If the shadow resembles a winged stag, then clearly all is well – but what if it resembles a man...?

A second photo of Linlithgow Palace's winged stag statue

A second photo of Linlithgow Palace's winged stag statue

According to fable, the perytons were once a mighty race of noble beasts that inhabited the mountainous peaks of Atlantis. Here they lived in peace with all living things, until humanity’s evil gradually spread like a vile cancer across the entire expanse of this vast and glorious island continent. Eventually even the gods despaired of the Atlanteans, whose skills in the dark arts threatened the existence of the entire world, and so it was decided that Atlantis and all of its heathen practitioners must be destroyed. The gods duly besieged the continent with earthquakes, tidal waves, plagues, and, most catastrophic of all, an immense volcanic eruption that decimated Atlantis and finally sank this once-illustrious land beneath the waves, staining with blood and ash the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean.

Just before it vanished forever, however, the perytons were able to flee, flying far from their doomed homeland to find sanctuary amid the high peaks of Greece and also, on the far side of the Mediterranean, those of Carthage and elsewhere in North Africa. Here these formidable creatures vowed to take relentless, bloody revenge on all mankind for the annihilation of their idyllic Atlantean domain. If a peryton saw an opportunity to kill a human, it would take it unhesitatingly, and would be assured of success on account of its invulnerability to all weapons created by men. Moreover, once a peryton had killed a human, it would gain a prize valued beyond all others by these creatures. Fortunately for humanity, however, each peryton could only kill a single human with impunity – after that, its invulnerability was lost and it too could therefore be slain. But what were perytons – what did they look like? As will be revealed here, a peryton was unlike anything else that had ever existed, and so could not be mistaken for anything else – except, that is, when it resorted to a unique form of dark, fatal trickery.

After their enforced exile from Atlantis, a mighty flock of these lethal beasts had attacked a mighty Roman fleet led by the celebrated general Scipio as its flotilla of four-score war ships and countless accompanying transport vessels journeyed across the Mediterranean to sack Carthage, and the perytons had inflicted terrible carnage before they were eventually repelled with unparalleled success by Scipio’s formidable troops. Since then, the perytons had remained concealed and aloof from humans in their mountainous retreats, humiliated by their unwonted defeat and gradually diminishing in numbers as the centuries slipped by, until they had become largely forgotten by the world beyond their remote peaks, relegated like the harpies, the minotaur, and other monstrosities of long ago to the neverland of nightmare. But very occasionally, a nightmare can become a reality...

An interesting variation - Una Woodruff's spectacular painting of a blue, horned peryton in her superb book Inventorum Natura (1979), which attempts to recreate the lost journal of Pliny the Elder ((c) Una Woodruff)

An interesting variation - Una Woodruff's spectacular painting of a blue, horned peryton in her superb book Inventorum Natura (1979), which attempts to recreate the lost journal of Pliny the Elder ((c) Una Woodruff)It had been a weary journey for the once-valiant, now-broken knight crusader, returning to his Greek homeland not in jubilation but rather in desolation for all of his dead and dying comrades, and accompanied only by his faithful squire. During the past weeks, they had ridden far indeed from the hideous scenes of bloodshed and mayhem that they had experienced for so long but had now left behind amid the corpse-strewn battlefields of the Holy Crusade. Yet those same scenes, and even worse ones, still rampaged with unending fervour in their shattered minds and within every nightmare that their fevered, ever-disturbed bouts of sleep generated.

And now, scarcely had they returned home before their friends, neighbours, and other townsfolk had beseeched the knight to seek out and vanquish a mysterious monster that had supposedly been glimpsed from time to time amid the dark, forbidding mountains close by during his absence. No-one was certain of the beast’s appearance, but all were certain that it existed. And so, armed with lance and shield, the knight, accompanied once more by his trusty squire, set off along the lonely path that wound its way up through the forests towards the plenitude of caves and caverns that pitted the mountainsides like pockmarks on the face of a titan.

Who knows what the knight would face if he did indeed encounter a monster there? Having said that, the dread beasts of ancient Greek tradition were just stories and legends, weren’t they? And even if they had been real once upon a time, surely that time was long since past now? Then again, certain of those entities were said to be immortal, such as the twin sisters of Medusa - she of the petrifying stare and snake-locked hair. Could that be what lay ahead, lurking in wait for him – the last of the gorgons? Or might it instead be a conflagrating multi-headed dragon, or even a hag-faced harpy with foul wings and fouler breath, ready to tear him apart with her crooked beak and talons of steel?

At least such thoughts, unpleasant though they unquestionably were, had succeeded in supplanting those previously tenacious images of the battlefield’s carnage. So, in a strange way, the knight’s mood had actually begun to lighten and lift as he and his squire continued their cautious ascent along the mountain path.

By now, their little town had been left far behind, so far that it could no longer be clearly discerned even from their lofty vantage point. And ahead? A grey vista of cliff faces, cloud-embraced peaks, and shadowy cave mouths surrounded them. The monster, if it did indeed exist, could be anywhere – so where should they begin their search?

As if in answer to their unspoken question, a cry suddenly echoed forth from the bowels of a tall but fairly narrow cave to their left, whose entrance was at the end of a high corridor-like passage through some rocks. The knight and his squire paused, listening closely, and the cry came again. It was a human voice, surely, a man’s voice, calling out for help, pleading to be rescued before the monster appeared!

Armed and ready for mortal combat ((c) Dr Karl Shuker)

Armed and ready for mortal combat ((c) Dr Karl Shuker)The knight and squire rode closer, but the knight was well aware from the ancient legends and superstitious folklore of his land that many monsters had successfully lured men and women to their doom by skilfully imitating a human voice. And so the knight called out, in the direction of the passage, for whoever was crying forth to show himself, and thus prove that he was human.

For a few moments there was silence, then came the sound of something moving slowly down the passage, until a shadow fell upon the exposed rock face at the passage’s entrance. It was the shadow of a man, a little stooped, perhaps, as if elderly or ailing, but undeniably human.

When the knight saw this, he and his squire rode up, approaching the entrance – but just before they reached it, the knight’s horse gave a wild neigh of fear and tried to swerve away, shaking in terror. Yet all that could be seen was the lone shadow of the man.

The knight looked away from the entrance as he sought to gain control of his panicking steed, which by now was thrashing its head from side to side and frothing madly in uncontrollable fright. And so it was his squire that saw who – or, rather, what – emerged from the passage to confront them.

Hearing his squire’s shrieks of horror, the knight turned back to look at the cave, and there, rearing up on its hind legs, was a beast that even in his wildest nightmares he had never thought of as anything other than fable and lurid fantasy. Yet here it was right now – only too real, and only too ready to kill him. It was a peryton!

On first sight it resembled a huge stag, sporting a pair of magnificent branching antlers, but as it reared directly in front of him, flailing its gleaming hooves, an enormous pair of plumed wings, sprouting from its shoulders, spread forth like the very pinions of Pegasus. And instead of fur, this unnatural creature was clothed in dark-green plumage, like some monstrous miscegenation of deer and tropical bird.

But most bizarre and uncanny of all was its shadow, which confirmed the creature’s identity as a bona fide peryton, albeit quite possibly the very last of its kind remaining on Earth. For there, cast upon the rock face as before, was not the shadow of a winged, feathered deer but instead the perfect facsimile of a human shadow – that which had fooled and lured the knight and his squire to the lair of this terrifying relic from an earlier world, whose eyes of fire and savage mien revealed only too readily its murderous intent.

For if a peryton should succeed in killing a human, not only would it rid the world of yet another member of the race that it would forever blame for the destruction of its own species’ blessed homeland, it would also gain something uniquely precious for itself – its own true shadow, the shadow of a peryton. Even so, upon killing a human a peryton would lose its resistance to man-made weapons, but that was a small price to pay – and it was evident that the peryton confronting the knight and his squire was more than willing to pay it.

All of this the knight knew only too well, as did his squire. In short, to vanquish this monster from a vanished land one of them must meet a grisly end - gored to death by the peryton’s antlers, then ripped asunder and trampled into the earth by its razor-sharp hooves. Undaunted, however, the knight swiftly dismounted from his nervy steed, and with shield and lance at the ready he slowly advanced on foot, signalling to his squire to stay back and hold his horse fast, in case he should need it. Perhaps the peryton possessed some vulnerable spot not spoken of in the old stories and myths – if so, he would find it, or die in the attempt.

Lowering its great head, the peryton eyed the knight with vibrant hatred, then charged toward him like a bull before a matador, but the knight fended it off with his burnished shield, rather than with a cloak of scarlet, which directed beams of sunlight into its eyes, temporarily blinding the raging creature and granting the knight precious moments in which to scrutinise it at close range in the hope of spying some weakness, some flaw, that might engineer its destruction.

But there was none.

If only he had known before ascending the mountain that the monster he would face there would be a peryton, he could have prepared himself accordingly, by abandoning human weapons and utilising the natural elements instead, against which the peryton had no invincibility. Fire or water to drive the creature back into its cavernous hideaway, and then perhaps the triggering of an avalanche in this unstable, rocky terrain, in order to imprison it inside the cave forever with a barrage of falling boulders sealing the entrance. That strategy might have succeeded, but now, now it was all too late.

A further representation of a peryton ((c) Tim Morris)

A further representation of a peryton ((c) Tim Morris)Time and again the peryton charged, and each time the knight deflected it with his shield, in a chilling dance of would-be death, but he was tiring. Months of fighting in the Crusade and weathering the most traumatic and draining of living conditions had severely weakened him – a lengthy respite from all forms of conflict was what he needed to recuperate, not a mortal battle with a monster of the peryton’s stature and power.

Suddenly, as he attempted yet another feint of the peryton’s antlers with his shield, the knight lost his footing, dropping his lance onto the ground as he stumbled backwards, falling awkwardly against the trunk of a tree. And in those few seconds while he struggled with the weight of his armour to stand upright, the peryton saw its opportunity and charged directly at him, hitting him with such force that his armour’s breastplate split down the centre, exposing his chest to the sharp tines of the peryton’s antlers. They pierced his torso with such force, impaling him upon themselves, that the peryton was momentarily pinned by its own antlers into the tree’s hard trunk, before, with a mighty heaving movement, it hauled them back out.

Freed from their deadly tines, the body of the dying knight slumped to the ground. His head turned one last time, to look at his squire, who stood transfixed with horror and rage at his master’s fate, and he smiled gently. By meeting his own demise at the antlers of the peryton, he had saved his squire, who had also been his friend for more years than either of them could remember, and so there was no shame in his defeat, only quiet thankfulness. The knight closed his eyes, and then, finally at peace with a world in which he had lately seen so much turmoil and terror, he died.

And at that same moment, the peryton let out a roar of triumphant joy, for as it gazed at its shadow against the rock face, the shadow began to shiver and tremble. Its outline became blurred and its form extended and expanded, rapidly transforming – until, within just a few moments, the shadow of a man had metamorphosed into the shadow of a peryton.

Exultant, the peryton opened its great wings, ready to depart elsewhere, to seek out a more remote land where, now that it was no longer impervious to human weapons, it could live on in safety and anonymity. But still it gazed at its new shadow, delighting in its appearance after dreaming of and waiting so long for this supreme moment, this ultimate triumph.

And so it never saw the squire creep across the ground and seize the lance of his dead master, and it never saw the squire take the lance in his right hand, pull back his arm, and take deadly aim with the lance at the peryton’s own chest. It never heard the squire’s muttered prayer to the God who had kept him and his master safe during the horrors of the Crusade, and it never felt the strong breeze that seemed to blow in from nowhere, lifting, bearing, and empowering the lance as the squire hurled it with all his might at the peryton’s chest.

The squire’s aim, guided surely by the divine breeze, found its mark – spearing the shocked peryton through the very centre of its beating heart, skewering it like a moth impaled upon a lepidopterist’s pin. Open-mouthed, the peryton turned its head to meet the flushed face of the squire, and as it sank to its knees, the last vision that the slain peryton saw was the squire’s own eyes, suffused with the raging, glowing fire of retribution as he watched with grim satisfaction the peryton’s death. He had avenged his master, his friend, and as he knelt before the knight’s body in thankful prayer for his success in doing so, the breeze momentarily caressed his cheek before disappearing as swiftly and mysteriously as it had arisen - leaving the squire in silent vigil.

Here in the mountains, he would remain, guarding the knight’s body throughout the oncoming hours of nightfall and darkness in a lone vigil, until the dawn’s first light, when he would then descend the winding path leading to their little town and seek help there in transporting with all due reverence and care his master back home, for the last time.

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges (featuring Peter Goodfellow's fantastic front cover painting)

The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges (featuring Peter Goodfellow's fantastic front cover painting)According to Jorge Luis Borges’s classic work The Book of Imaginary Beings (1969), which is often said to be the first modern-day book to document perytons, all of the information concerning these creatures that is known today is derived from a 16th-Century Fez rabbi’s historical treatise, or, rather, from the now-lost work of an unnamed scholar from ancient Greece that the rabbi had quoted in his own treatise. Borges asserted that until the outbreak of World War II, the single known copy of that treatise was held in the University of Dresden’s library. Tragically, however, perhaps as a result of the severe bombing of this German city by the Allies, or of the Nazis’ own notorious book-burning sessions, by the end of the war the rabbi’s unique manuscript had gone missing, and has never been found again – nor, indeed, has any additional copy of it.

Having said that, some authorities have suggested that Borges invented the entire peryton myth himself (including his assertions concerning the supposed erstwhile existence of the rabbi’s treatise, as well as another claim by him, that a sibyl had foretold – wrongly – that a phalanx of perytons would destroy Rome); and that, in fact, there was no peryton lore or tradition whatsoever prior to his book. However, there are several notable sources of winged deer information and portrayals (especially in heraldry, Western architecture and sculpture, early Hindu art, occultism, and even antique jewellery) that very considerably pre-date the publication of Borges’s book. Whether they are meant to represent genuine perytons is unclear, but they certainly exist.

As noted, for instance, in K. Krishna Murthy’s book Mythical Animals in Indian Art:

"The winged deer or stag...gets its sculptural representation more than once in the early Indian sculptures. However, the best specimens of the winged stags can be seen in the reliefs of Sanchi. A clear example of two winged stags sitting back to back occurs on the front of the northern Torana gateways."

Nor should we – or, indeed, could we – overlook the visual extravaganza that constitutes the glorious fountain replete with golden statues of winged deer that forms part of the huge garden around La Granja – the sumptuous palace in Segovia, Spain, that was built in 1721-24 by Philip V.

Perhaps the most distinctive British example is the ornate statue of a winged stag sitting upright on its haunches that is just one of many large, intricately-detailed sculptures of fantastic beings forming part of the elaborate fountain in the courtyard of West Lothian’s Linlithgow Palace. Nowadays, this Scottish palace is largely in ruins internally, but the fountain still survives and dates back to the reign of King James V (1512-1542).

Statue of a green winged stag at Linlithgow Palace ((c) amyhooton/deviantart)

Statue of a green winged stag at Linlithgow Palace ((c) amyhooton/deviantart)Although the fountain’s winged stag statue may simply represent a composite heraldic beast, it is interesting to note that algal growth has turned it green in colour – the same colour that the perytons were said to be. Just a coincidence? Perhaps the next time that anyone visits this fountain, they should take note of the shadow cast by the winged stag’s green statue. If the shadow resembles a winged stag, then clearly all is well – but what if it resembles a man...?

A second photo of Linlithgow Palace's winged stag statue

A second photo of Linlithgow Palace's winged stag statue