As revealed in Part 1 of this three-part ShukerNature article (click here to read Part 1), eyewitness descriptions of elusive kangaroo-like beasts sighted across North America vary considerably from one to another – to the extent whereby it is possible to divide such creatures, based upon their reported morphological and behavioural attributes, into several categories. Clearly, therefore, more than one type of animal is involved in the enigma of America's mystery macropods, as will now be demonstrated.

ESCAPEE THEORY

The majority of reports describe animals that resemble and behave like normal kangaroos and wallabies; such creatures are readily identified by their observers as macropods, and do not appear in any way strange in themselves (except for the ease with which they evade capture). They are made mysterious in fact only by being macropods in America – and thereby out-of-place and of undetermined origin. Hence it seems likely that such animals are indeed normal, known species of kangaroo and wallaby – but where have they come from?

In their native Australian homeland, certain macropod species, e.g. the red kangaroo Macropus rufus and certain wallabies, inhabit open plains and semi-desert areas, whereas various other wallabies and the eastern grey kangaroo M. giganteus prefer woodland regions. Such habitats are of course also found in America, and correspond closely with their Australian counterparts. Accordingly, if any American captive specimens (maintained as exhibits in zoos, circuses, and parks, or in private households as pets) have escaped in the past, the chances are that if they were fortunate enough to locate habitats comparable with those of their native Antipodean homeland, then they survived.

Additionally, if a pair (or indeed a number) of specimens escaped together, they may well have established a thriving naturalised population (as has happened in several different, widely dispersed localities within the U.K., for instance – see later). Having said that, the theory of escapees has been put forward so frequently to explain away sightings of mystery or out-of-place beasts in America, Britain, and elsewhere that it has virtually become a cryptozoological cliché. In some cases, moreover, it is painfully inadequate as a satisfactory solution to such sightings.

In the case of the 'normal' category of New World phantom kangaroos, however, it does present itself as a tenable solution. Certainly, many sightings of such beasts can be compared favourably with known species. The 5-6-ft reddish-brown individuals are plausibly identifiable as male red kangaroos; comparably-sized greyish-black specimens are likely to be either female red kangaroos or eastern grey kangaroos; both species are common zoo exhibits. Similarly, the 3-ft specimens resemble various wallaby species. Indeed, the creature photographed in colour at Waukesha, Wisconsin, during April 1978 (see Part 1 of this present article) specifically resembles Bennett's wallaby Notamacropus rufogriseus (as also noted by Coleman in Mysterious America), native to Tasmania but a very frequent exhibit in zoos and parks worldwide.

The moniker of 'phantom kangaroo' has been applied to America's mystery macropods on account of their extreme elusiveness, in turn implying a paranormal connection. However, it should be remembered that all but the very biggest macropods are relatively defenceless and all are herbivores, thereby constituting the natural prey of large carnivorous species – which in Australasia meant (until relatively recent times, geologically speaking) not only the Tasmanian wolf (thylacine) and dingo but also the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. Consequently, a well-developed capacity for evanescence and concealment is a survival necessity for macropods.

Added to this is the fact that escapee macropods will clearly be very disoriented at first, unexpectedly finding themselves in totally unfamiliar surroundings with their previous, familiar routine of existence now gone. Their response (and that of any intelligent animal faced with such a situation) will be to display enhanced defensive and protective behaviour whilst acclimatising to their new surroundings. Moreover, as they will soon discover, in North America these new surroundings contain several very hostile species, which may include pumas, bobcats, lynxes, wolverines, wolves, bears, and humans toting rifles, thereby reinforcing and perpetuating such wariness upon the part of the macropods thereafter.

Consequently, if America's 'normal' contingent of phantom kangaroos does indeed consist of escapees and their wild-born descendants, it should be no surprise to learn that they are exceedingly elusive. Any incautious individuals will be killed very quickly following their original escape, by the predators already listed.

One final point concerning the escapee theory is that escapees are not always reported to the authorities – especially if they were pets or inhabitants of private collections and (as a result, for example, of such escapees having been brought into the country illegally, or having caused any disturbance, etc, while on the loose) their owners may themselves falling foul of the law. Indeed, unreported escapees (plus deliberately-released unwanted pets) have been responsible for establishing populations of exotic animal species in many parts of the world, and will no doubt continue to do so, albeit to the inevitable detriment of the native fauna.

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

One option that must always be considered when dealing with mystery creatures is the possibility that at least some such sightings are actually misidentifications of known native species.

Among the North American rodents is a group constituting the genus Dipodomys – the kangaroo rats. As one might expect from their name, these possess notably long hindlimbs and tail, much shorter forelimbs, and move via powerful bipedal bounds, thereby paralleling genuine macropods and occupying in America a similar ecological niche to that filled in Australia by some of the smaller desert-living macropods.

Kangaroo rats inhabit dry or semi-dry sandy country, and are distributed from southwestern California southwards to central Mexico. The larger species, e.g. the giant kangaroo rat D. ingens, attain a total length of almost 2 ft. They are generally nocturnal creatures, but certainly any individuals observed at dawn or dusk could be mistaken for small wallabies. Indeed, kangaroo rats may well constitute the true identity of some of the so-called "baby kangaroos" that have been reported from many U.S. regions over the years.

Another instance of mistaken identity may perhaps be responsible for the second category of American phantom kangaroos. Although true kangaroos and wallabies adopt a quadrupedal posture not only when grazing but also while moving slightly when grazing, their mode of locomotion under all other circumstances is invariably one of bipedal bounding, with their tail stretched out horizontally behind and their body held comparably. Hence true macropods would not appear to be the identity of those wallaby-sized, less-frequently spied American 'kangaroos' that hop rapidly on all fours.

One group of native New World creatures, however, whose members are of comparable size and which do behave in this manner, consists of the surface-dwelling jack rabbits (which are actually hares!) of the western United States. Even so, there are certain problems with equating the quadrupedal 'kangaroos' with jack rabbits.

Firstly, whereas the former creatures apparently resemble typical macropods in all but their mode of progression, jack rabbits have notably short tails and long ears. Also, in view of the very familiar appearance of jack rabbits, it is difficult to imagine that they could be mistaken for kangaroos by observers. The same principle applies to suggestions that such beasts were really misidentified fawns. There is also the problem of the 5.5-ft-tall quadrupedal 'kangaroo' sighted by Louis Staub in Ohio as detailed in Part 1 of this article. No known lagomorph attains such a size. Equally, Staub specifically stated that he was sure that the creature was not a deer.

EXOTIC EXPLANATIONS

One final animal species well worth mentioning in the context of quadrupedal macropod-like beasts is the mara or Patagonian cavy Dolichotis patagonum. This most interesting creature, a guinea-pig relative, is about 2.5 ft in total length, and is very distinct from more typical cavy species, having evolved notably long hind limbs and exhibiting a cursorial mode of existence. Intriguingly, however, its overall appearance when standing is reminiscent of a small macropod on all fours.

Could this specialised rodent therefore be responsible for some of the quadrupedal 'kangaroo' reports from the States? Sadly, the mara's distribution range is limited to South America's southern half. Consequently, although this species certainly bears comparison with the description of such creatures (especially the smaller ones), it would naturally be quite ludicrous even to contemplate the possibility of native maras having any involvement in America's phantom kangaroo phenomenon – but escapees from captivity are another matter, especially as this species is often exhibited in zoos.

Indeed, as Loren Coleman reported in Fortean Times (spring 1982): following a spate of mystery macropod sightings in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during summer 1981, a strange bounding creature was actually captured right in the heart of Tulsa on 27 September of that year – and was found to be a mara. Its origin has never been ascertained, but it was presumably an escapee from captivity. Could an elusive naturalised population exist in that region, I wonder, descendants of original escapees? Certainly the Tulsa environment is compatible with mara survival.

It is evident that America's quadrupedal 'kangaroos' have yet to be identified with any degree of certainty. Clearly, therefore, it would be beneficial for future reports and sightings of such animals to be investigated in especial detail, and for them to be formally recognised hereafter as distinct entities from genuine phantom (i.e. 'normal') kangaroos.

Equally enigmatic, but equally likely to have an exotic explanation, is the 4-ft-tall bipedal creature – sporting a greyhound-shaped head, short brown fur, and a long tail held vertically with a distinct curl at its tip – sighted by a Mr Workman at Tucson, Arizona, during the early 1960s, as detailed in Part 1. Although bipedal and, according to Workman, resembling in outward appearance a kangaroo, it did not move via hopping but via walking – and on notably small hind feet. These latter features clearly dismiss a macropod identity from further consideration. So too does its vertically-held, curl-bearing tail (macropod tails are uniformly straight and are held horizontally). Clearly this creature merits its own category relative to other phantom kangaroo sightings.

However, although superficially perplexing, a most plausible solution has in fact been put forward with regard to its likely taxonomic identity. In a reply published beneath the original letter concerning this animal (ISC Newsletter, spring 1982), J. Richard Greenwell – Secretary of the International Society of Cryptozoology (ISC) – suggested that the latter could have been a coati.

Coatis are lithe relatives of the raccoons, kinkajou, cacomistles, and other procyonid carnivores. They attain a total length of 4 ft, possess a slender head, and a highly inquisitive nature, in turn bestowing upon them a tendency to stand upright in order to observe more accurately any object that attracts their attention. Worthy of especial note – their tail is held vertically, and curls at its tip.

Moreover, although coatis constitute a primarily South American taxon, the distribution of the common coati Nasua narica extends as far north as the southern U.S.A., including Arizona. So far, therefore, the coati and Workman's creature accord very closely both morphologically and geographically. Even so, there are certain difficulties. The latter beast's head-and-body length alone measured 4 ft (its tail length was additional to this), and it actually walked bipedally. Coatis, conversely, do not attain this beast's total size; nor do they typically do more than stand bipedally – when moving, they usually bound on all fours.

However, it is certainly possible that Workman overestimated the creature's size. Equally, some coati individuals will in fact walk at least a short distance bipedally, just like their larger relatives the bears. Indeed, in Part 1 of this article I included a link to a photo of a coati doing precisely that (here it is again); I have also personally witnessed a pet coati walking bipedally of its own free will (like a true cryptozoologist, however, I did not have a camera with me at the time to photograph this noteworthy behaviour!). In any case, the otherwise striking correspondence between Workman's animal and a coati – even to the curl-tipped, vertically-held tail – suggests that this is indeed the correct identity for that particular mystery animal.

Worthy of brief mention here is another phantom kangaroo case with procyonid pertinence. Following the fraught encounter by two policemen in 1974 with an irascible, 5-ft-tall macropod lookalike nicknamed the Chicago Hopper as detailed in Part 1, a mystery creature was in fact captured nearby. Not only that, it was actually offered as the Chicago Hopper's identity. In reality, however, this was a quite ridiculous state of affairs, because the captured critter in question was a kinkajou Potos flavus – a golden-coloured relative of coatis and raccoons, but which only attains a total length of 2.5 ft, and looks nothing whatsoever like a kangaroo! The fact that the kinkajou is restricted in the wild state to Central and South America raises some interesting questions regarding the capture of a living specimen in Arizona, but as the latter's species is a popular exotic pet and zoo exhibit, it was probably just another escapee or deliberate release from captivity. Regardless of origin, however, it was clearly unrelated to the Chicago Hopper incident.

COUGH-LIKE SOUNDS

The Chicago Hopper is a representative of the last phantom kangaroo category delineated by me in Part 1, and whose members I dubbed there as aggressive growlers and shriekers. However, although united by their bellicose behaviour and vehement vocals, this category's members morphologically constitute a rather heterogeneous gathering. Consequently, as it is likely that more than one taxonomic identity is involved here, the principal examples will be considered individually.

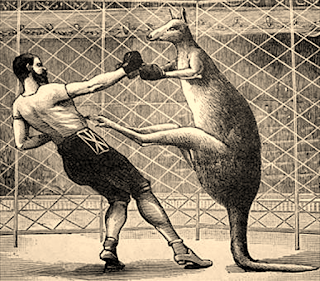

Judging from the reports on record concerning the Chicago Hopper, this was in every way a normal kangaroo – except, it appeared, for its pugnacity and unexpected utterance of growling noises. Let us now examine these latter attributes closely. It attacked by using its hindlimbs as formidable kicking instruments – which is typical kangaroo behaviour. Furthermore, although many people apparently believe that kangaroos are actually mute or at least not prone to vocalisations of any form, in the event of imminent danger all adult kangaroos (but especially males) in fact produce notable cough-like sounds. These serve to alert all other kangaroos nearby.

When approached by the two policemen, the Chicago Hopper clearly considered itself to be under threat, and the two responses that it displayed were those that characterise adult kangaroos when exposed to such circumstances – it voiced its cough-like alarm signal (which could certainly sound like growling, especially to two witnesses who were probably not expecting such noises from a kangaroo), and it defended itself from possible attack by using its hind legs as weapons. In short, there is no reason whatsoever to consider further that the Chicago Hopper was anything other than a normal kangaroo. Of course, its origin is still a mystery, but as it is assuredly a 'normal' phantom kangaroo the possible solutions to this riddle have already been dealt with earlier here.

Conversely, the rapacious Tennessee "kangaroo" that attacked, killed, and partly devoured waterfowl and even a number of large dogs in 1934 is a very different matter. The problem with this particular case is that no report giving any specific morphological features concerning the animal appears to have been documented – it was simply described as resembling a "giant kangaroo". However, if the reports of its carnivorous activity are accurate, then it was most certainly not a macropod. (Having said that, such creatures are not entirely unknown to science – during the Australian Miocene epoch, around 20 million years ago, Queensland was home to some sizeable meat-eating macropods, belonging to the now long-extinct genus Ekaltadeta.) Additionally, the Reverend W.J. Hancock informed the New York Times that it was seen "...running across the field". As noted earlier, macropods do not run.

Beyond this, however, it is virtually impossible to speculate regarding this cryptid's identity. If in spite of its carnivorous behaviour it resembled a kangaroo as far as its eyewitnesses were concerned, then presumably it was bipedal. Could it therefore have been a bear? Possibly, but surely it would be difficult to confuse a bear with a kangaroo. Sadly, it is likely that this intriguing mystery beast will remain mysterious, unless any report regarding it is uncovered that provides further morphological details.

Yet what of the shrieking mystery macropods? What might these be? As will be seen in Part 3, the concluding part of this ShukerNature blog article (click here to read it), one of the exciting possibilities concerning phantom kangaroos (especially the more bizarre forms) is that a totally unknown species may be involved. And don't forget to click here to read Part 1 if you haven't already done so.

Kangaroos and wallabies make a definite growling noise as well as a cough. The growl is a throaty sound. It does not project very far. It is more for close aggressive communication.

ReplyDeleteThe misidentification theory reminds me of a story I heard from a coworker. She had worked at a golf course and someone came in to complain of monkeys all over the golf course! ...........They were Fox Squirrels. lmao

ReplyDeleteIt never fails to amaze - and amuse - me that even the most mundane, familiar animals can sometimes be misidentified dramatically if observed by people with little if any interest in or knowledge of the creatures sharing their environment. This is a wonderful example - thanks very much for posting it here, Lucas!

DeleteThe Chatata biped, to my eye, has certain features of an adult male wild turkey. The wavy "beard" on the head resembles a long snood and the jointless curved appendage interpreted as a kangaroo's forelimb has the same shape as a male turkey's "beard" of filamentous feathers. The odd backward projection of the foot may represent a turkey hallux projecting posterior of the leg. The tail is a poor but not inconceivable match for the posture of the turkey tail when walking. The "ears" and the proportionally large size and blunt snout of the head remain mysterious.

ReplyDelete