Behold, Pigasus! (public domain)

"The time has come," the Walrus said,

To talk of many things:

Of shoes - and ships - and sealing-wax -

Of cabbages - and kings -

And why the sea is boiling hot -

And whether pigs have wings."

Lewis Carroll - Through the Looking-Glass

Some time ago, in a previous ShukerNature blog

article (click here to read it), I wrote

about flying elephants – as you do. So it was only ever going to be a matter of

time before I followed that up with an article on flying pigs – and here it is.

When I was a child, and sometimes even as an adult,

if ever I voiced an idea that she considered highly implausible, or overly

fanciful (even by my normal standards!), my mother Mary Shuker would often give

me a certain, very specific half-smile, her eyes dancing with humorous

laughter, and say: "Yes, and pigs might fly!".

In one form or another, that expression, and its

meaning as used by Mom, has been around for a very long time. Indeed, it

possibly originated as "Pigs fly in the ayre with their tayles

forward" – a rejoinder denoting amused or sarcastic disbelief, and

appearing in a list of proverbs within the 1616 edition of John Withals's

English-Latin dictionary A Shorte

Dictionarie for Yonge Begynners.

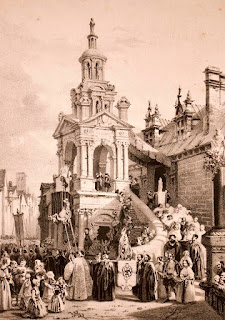

Satirical American political news

illustration from 1884 featuring Uncle Sam alongside the flying pig motif in

its typical representation of something highly implausible if not downright

impossible (public domain)

In any event, just like the fictitious beast known

as the hippogriff initially was, it is synonymous nowadays with anything

extremely doubtful or impossible to exist, or at least be even remotely likely

to do so. Hence it is an example of a specific type of figure of speech known

as an adynation (and for my ShukerNature coverage elucidating this conceptual link

to the hippogriff, please click here).

Nevertheless, one of the numerous telling lessons

in life that I've learnt by way of investigating cryptozoological cases is that

if you look long enough and hard enough – and sometimes if you don't actually

look at all – even the most implausible and unlikely things will be found. And

so indeed it has been with flying pigs and other porkers on the wing, as will

now be seen.

Pigs with wings – impossible things?

(Image found abundantly online, but its creator and © owner are currently

unknown to me, despite having made extensive searches – reproduction here on a

strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

The first instance of an allegedly airborne entity

of the porcine persuasion that I ever encountered, and which is still the most

perplexing to me, featured in a short report from 1905 briefly paraphrased in Living

Wonders: Mysteries and Curiosities of the Animal World – a unique and

thoroughly fascinating compendium of reports and analyses concerning all manner

of anomalous animals and animal anomalies compiled by veteran Fortean

writer-researchers John Michell and Bob Rickard, and first published in 1982 (a

much-expanded, fully-revised edition appeared in 2000, entitled Unexplained

Phenomena: A Rough Guide Special, which combined Living Wonders

with an earlier book written by the same authors, Phenomena, published

in 1977, but, sadly, did not include any flying pigs within its pages).

I subsequently discovered a more detailed

documentation of this very curious case in New Lands (1923) – one of the

tomes in pioneering anomalies chronicler Charles Fort's peerless tetralogy documenting and passing comment upon all manner of unconventional occurrences.

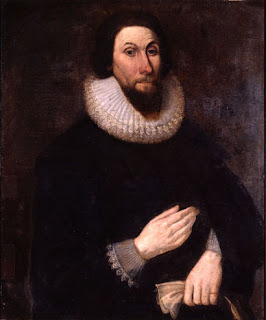

Charles Fort (public domain)

Here is what Fort wrote:

Sept. 2, 1905—the tragedy of the

space-pig:

In

the English Mechanic, 86-100, Col. Markwick writes that, according to the

Cambrian Natural Observer, something was seen in the sky. at Llangollen, Wales, Sept. 2, 1905. It is described as an intensely black object,

about two miles above the earth's surface, moving at the rate of about twenty

miles an hour. Col. Markwick writes: "Could it have been a balloon?"

We give Col. Markwick good rating as an extra-geographer, but of the early, or

differentiating type, a transitional, if not a sphinx: so he was not quite developed

enough to publish the details of this object. In the Cambrian Natural Observer,

1905-35 — the journal of the Astronomical Society of Wales — it is said that,

according to accounts in the newspapers, an object had appeared in the sky, at

Llangollen, Wales, Sept. 2, 1905. At the schoolhouse, in Vroncysylite [= the

village of Froncysyllte, or Fron for short]…the thing in the sky had been

examined through powerful field glasses. We are told that it had short wings,

and flew, or moved, in a way described as "casually inclining

sideways." It seemed to have four legs, and looked to be about ten feet

long. According to several witnesses it looked like a huge, winged pig, with

webbed feet. "Much speculation was rife as to what the mysterious object

could be."…

I

don't know that my own attitude toward these data is understood, and I don't

know that it matters in the least: also from time to time my own attitude

changes: but very largely my feeling is that not much can be, or should be,

concluded from our meager accounts, but that so often are these occurrences, in

our fields, reported, that several times every year there will be occurrences

that one would like to have investigated by someone who believes that we have

written nothing but bosh, and by someone who believes in our data almost

religiously.

One can readily understand and sympathise with

Fort's evident bemusement at such a report. After all, how can a

supposed sighting of a very sizeable pig with wings and webbed feet flying

through the sky be rationally explained if not an outright hoax or a

misidentification of truly monstrous proportions? To my knowledge, no similar

creature has been reported above Wales (or, indeed, anywhere else) since then, so

whatever this veritable Pigasus was, at least it wasn't breeding – which is a

mercy in itself!

Might the Welsh flying pig have

looked something like this? (public domain)

Had its one-off appearance taken place at some

rather later date, I might have suggested that Wales's wayward Pigasus could

have been some kind of man-made object that had originally been produced to

feature in some form of advertising campaign but which had broken free from its

tethering bonds and absconded skywards – if only because one such ostensibly

unlikely incident featuring an airborne pig actually did occur.

On 4 December 1976, an article documenting this incident's bizarre

events of the previous day, written by Clive Borrell, featured in Britain's most respectable, and respected, newspaper – London's daily broadsheet The Times. And the precise

subject of that article? An enormous pink pig floating at an altitude of 7,000

ft and causing a very real, if decidedly surreal, hazard to aircraft!

Reports of this identified yet highly unexpected

flying object, originating from unbelieving pilots, had found their way to

police at London's Scotland Yard, as noted by Borrell in his

article. And when he asked one of the Yard's representatives for more details,

this is what he was given:

"At

10.25 this morning [3 December] a pink pig balloon measuring 10 metres by five

metres [just over 30 ft by 15 ft], escaped from its mooring in the car park of

Battersea power station. It was there to advertise the pop group, Pink Floyd,

but it broke loose.

One

of our helicopters on traffic patrol intercepted a radio message from a light

aircraft to the control tower at Heathrow airport. The pilot was heard to say:

"I've just been overtaken by a pink elephant at 7,000 ft."

The

helicopter crew offered to help because the control tower could not plot the

creature on their radar.

…We

escorted it across London as far as Crystal Palace. Now it's out of our

area."

Wisely ignoring the above-quoted pilot's evidently

poor zoological knowledge in confusing a pig with an elephant, Borrell went on

to note that by midday the huge hog-shaped balloon (filled with helium) was 20

miles east of London, passing over the Essex suburbs, and that the Civil

Aviation Authority was very amused indeed by this unheralded sky beast.

How it must have looked when the

floating pig balloon broke free – this photo is actually of the pig's return in

September 2011 – see later for details (© Christopher Hilton/Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Later that day, Essex police reported that the pig was beginning to lose height, drifting

now at an altitude of only 5,000 ft – perhaps it was hungry, they speculated.

But by mid-afternoon it had clearly regained strength, and altitude, soaring

majestically now at a height of 18,000 ft above Chatham, and seemingly heading towards continental Europe. Might it therefore be not so much a homing pigeon as a homing pig,

making its way back to Germany, where it was originally manufactured?

Tragically, we shall never know, because several

hours later, as revealed by Borrell in his Times article, the pig

began to deflate and eventually came down that same evening to land on a farm

at Chilham, near Canterbury, Kent, its escape to victory thwarted, its great

adventure ended. In all seriousness, however, its danger to aircraft had been

deemed sufficiently severe for flights at Heathrow Airport, London's biggest, to be cancelled.

(As a brief digression, I should note here that I

didn't see Borrell's article when it was originally published in December 1976,

but came upon it a decade later, reprinted within a wonderful compendium of Times

articles. published in 1985, which had been compiled by Stephen Winkworth, and

was entitled More Amazing Times! Moreover, I was so delighted to see

this article that I actually purchased the entire book just to have it, because

I knew that one day I'd be able to make use of it – and now, albeit many years

later, that day has finally come!)

Floyd

Pig, the embodiment of Pink Floyd's album, Animals, where the Pigs take

over in a George Orwellian world - backdrop from a Pink Floyd concert tour (© Craig

Carper/Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Researching this marvellously memorable incident, I

uncovered certain additional details, which are as follows. As all Pink Floyd

fans will instantly confirm, the purpose of this giant inflatable pig – which

had been officially dubbed Algie by the band – was to advertise and appear upon

the cover of their latest album, Animals, released in 1977, and which does

indeed feature a photograph of it, floating between two of Battersea Power

Station's chimneys – the photo being produced after Algie had been recovered,

repaired, and reinflated. Three of the five tracks on Animals feature

pigs in their titles.

Algie had been built by the artist Jeffrey Shaw,

assisted by design team Hipgnosis, after being designed by Floyd bassist and

songwriter Roger Waters. Algie subsequently appeared at a number of Pink Floyd

concerts, originally still pink in colour, but later black. After Waters quit

Pink Floyd in 1985, he continued to feature inflatable pigs in many of his solo

concerts, often brightly adorned with slogans, and sometimes deliberately

released into the sky.

Two views of flying slogans-inscribed pig from Roger Waters show at Hollywood Bowl on 13

June 2007

(© BeautifulFlying/Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

On 26 September 2011, an Algie replica was securely

tethered over Battersea Power Station and photographed to promote the band's

reissuing of their first 14 studio albums via their Why Pink Floyd…? re-release

campaign. And a pig floating above the station was also glimpsed in British

movie director Danny Boyle's much-acclaimed Isles of Wonder short film

shown as part of the Opening Ceremonies of the 2012 Summer Olympics held in London, UK.

Giant pig balloon flying over

Battersea Power Station, 26 September 2011, as part of Pink Floyd's Why Pink

Floyd...? re-release campaign (© Bex Walton/Wikipedia - CC BY 2.0 licence)

Clearly, old flying pigs never die, they just keep floating

on…

Speaking of old flying pigs: there are records on

file concerning such exotica that date surprisingly far back in time. Take, for

instance, the intriguing American account that appeared in The History of New England, 1630-1649, written by English Puritan explorer John Winthrop, who settled in Massachusetts during 1630 and became the Governor of

Massachusetts Bay Colony. The above-cited book is a transcription of his

original notes, and was published in 1908. In it can be found the following

passage:

In

this year one James Everell, a sober, discreet man, and two others, saw a great

light in the night at Muddy River. When it stood still,

it flamed up, and was about three yards square; when it ran, it was contracted

into the figure of a swine: it ran as swift as an arrow towards Charlton, and

so up and down about two or three hours.

Not so much ball lightning as boar lightning, it

would seem. One for the meteorologists rather than the mammalogists to ponder

over, I suspect.

Portrait of John Winthrop (public

domain)

As ShukerNature readers will already be aware,

medieval illuminated manuscripts have long fascinated me, because of the

extraordinary diversity of bizarre beasts painstakingly portrayed around the

margins of their text (as inscribed upon unbound, usually double-sided pages

known as folios, whose upper side or verso is usually abbreviated to v, and

whose lower side or recto as r). Known as marginalia grotesques, they occur in

every imaginable, and often entirely unimaginable, form. I have already

documented some of these extraordinary creatures here (snail-cats and other malacomorphs),

here (an elephant rat), here (a Star Wars

Yoda-lookalike), and here (a very

sinister, sharp-toothed Nosferatu doppelgänger).

Was it possible, therefore, that one or two pigs

with wings might also be found lurking among the illuminated letters of such

manuscripts, quite literally hogging the limelight? There was only one way to

find out, and that was to peruse a representative selection of them (happily,

many of the most famous of these exquisite medieval works are present in

fully-scanned form online). So that's what I did – and two delightful examples

were duly uncovered.

Winged pig from Le Livre des

Hystoires du Mirouer, Depuis la Création, Jusqu' Après la Dictature de Quintus Cincinnatus

(Bibliothèque Nationale de France/public domain)

One of these, a somewhat belligerent boar with a

pair of bright red bat-like wings, turned up in Le Livre des Hystoires du Mirouer,

Depuis la Création, Jusqu' Après la Dictature de Quintus Cincinnatus, a beautiful

illuminated manuscript dating from the 15th Century and consisting

of 41 folios. It is currently held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, where

it is listed as BNF Fr 328. The winged pig is present in the bottom left-hand

corner of the margin on f 29 v (i.e. on the verso side of folio 29).

The other one,

sporting a pair of proportionately larger, elaborately pleated wings, was

present in the Katherine Hours, an illuminated Book of Hours (click here for details of what these are) dating from

around 1480-1485. A lavishly-illustrated illuminated manuscript consisting of

over 100 folios, it was created at Tours in France by Jean

Bourdichon (1457-1521), who was court painter to four successive French kings.

It is held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, and earns its name from the intertwined initials 'I' and 'K', which appear frequently in the borders of

the manuscript, with the 'I'

embraced by a loop that forms the arms of the 'K'. As noted by the museum's online page

devoted to this manuscript, the letters are likely to be the initials of a

husband and wife who commissioned it. The 'K' probably stands for Katherine, because the

manuscript contains several prayers to Saint Catherine of Alexandria, after whom women in medieval France were often named. The winged pig appears in the

middle of the right-hand margin of folio 83, whose principal feature is a large

central illustration entitled 'The Man of Sorrows at the Last Judgement'.

Winged

pig from the Katherine Hours (J. Paul Getty Museum/public domain)

As for the

purposes of these and other zoological grotesques, I noted in my previous

ShukerNature articles regarding such entities that it is very likely that many were

created by the monks producing illuminated manuscripts as humorous or even

slyly rebellious adornments that also helped them to break or lighten the very

lengthy periods of excessive tedium endured throughout the very painstaking

process involved in the preparation of such manuscripts.

Moving forward

to the present day, greatly deserving of mention here is a very different but

equally eyecatching commemoration of winged pigs in art. Namely, the quartet of

statues known as the Cincinnati Flying Pigs with the Fish Head Shrouds, each statue

standing 4.5 ft tall, perched atop a smokestack column, and with a fish head

shroud sending forth a golden cable attached to the column. Created by the Doug

Freeman Studio, they were commissioned by Andrew Leicester with the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Museum, as part of the

entry for the Sawyer Point Park, in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Cincinnati has long been

nicknamed Porkopolis, due to its historical importance as a major centre of the

American pig industry, so if winged pigs were ever going to appear anywhere in

the USA, this was

always where they would do so. Furthermore, during the Big Pig Gig of 2000 and

the Big Pig Gig: Do-Re-Wee of 2012, events organised by a community employment

programme called ArtWorks, numerous life-sized fibreglass pig statues of

varying forms and colours were temporarily installed throughout Cincinnati's

downtown area, and many of these were winged pigs.

Another

spectacular work of art is the painting Fliegende Schweine ('Flying

Pigs'), produced by the acclaimed modern-day German artist, designer, and

sculptor Michael Maschka, a leading follower of the Fantastic Realism school of

art.

Sadly, flying

pigs have not featured extensively in mythology, so often a sanctuary for

esoteric entities of the zoological variety. Perhaps the most notable example,

occurring in Greek mythology, is Chrysaor. Resulting from a liaison between

Medusa (in her ravishing pre-gorgon days) and the sea god Poseidon (having

assumed mortal human form at the time), he is variously depicted as a young

human giant or a great winged boar. However, he was not born until Medusa was

beheaded by Perseus, arising from drops of blood seeping from her neck stump.

By a peculiar quirk that is so often the norm amid the bizarre biology all too

prevalent in myths and legends, Chrysaor's twin brother was none other than

that noble winged steed Pegasus, who was also born from slain Medusa's blood

according to some versions of this tale.

Certain items of

ancient Greek ware depict Chrysaor. These most famously include an Athenian black-figure pyxis vase portraying him as

a young human boy, and dating from c.525-475 BC, which is housed in the Louvre

Museum, Paris, France; and an Athenian red-figure kylix vase portraying him as

a winged boar on the shield of his son, the three-bodied giant Geryon, and

dating from c.510-500 BC, which is housed at the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State

Collections of Antiquities), a major archaeological museum in Munich, Germany.

Less familiar is the winged sow that according to

the Greek-speaking Roman scholar Aelian (c.175-235 AD), writing in his 3-volume

work On Animals, once terrorised the ancient Greek city of Clazomenae,

whose ruins can be found in what is now the Anatolian Turkish town of Urla.

Originally situated on the mainland, Clazomenae was subsequently moved to an

island just off the coast, lying west of what was then the Greek city of Smyrna, but is now the Anatolian city of Izmir.

A

flying pig used as a trademark by Baldwin, Farnum & Shapleigh, as seen on

this bill of sale from 1875 (public domain)

Flying pigs

sometimes occur as publicity emblems, as seen earlier here with Pink Floyd.

Other notable examples of such use include serving as the official mascot for

the Grand Prairie Airhogs (a semi-professional baseball team from Grand Prairie

in Texas), as the logo of the Flying Pig Brewing Co in Everett, Washington (in

operation as a microbrewery or brewpub from 1997 to 2005), and as the official

mascot for the Chesapeake Bay log canoe Edmee S. In addition, the

presence of flying pigs featured in many promotional posters for the fantasy

movie Nanny McPhee and the Big Bang (2010), and it goes without saying

that there are a fair few Flying Pig pubs, hotels, and restaurants worldwide.

Much as

I would love to do so, I cannot lay claim to having invented the name 'Pigasus'

– frustratingly, that singular honour(?) must go to children's author Ruth

Plumly Thompson. For it was she who included a flying winged pig of that name

in various of the 21 novels written by her during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1970s that

were sequels to the 14 original Oz books authored by L. Frank Baum. Pigasus

first appeared in Thompson's Pirates in Oz (1931), but played a much

bigger role in The Wishing Horse of Oz (1935).

Pigs with wings that

can fly evidently have great appeal for youngsters, because they have also

occurred in a number of later, non-Oz children's books. These include Clementina

the Flying Pig (1939) by Oskar Lebeck, Perfect the Pig (1980) by

Susan Jeschke, Porcellus the Flying Pig (1988) by Judy Corbalis, The

History of Flying Pigs (1991) by A.A. Barber, and Cincy the Flying Pig

(2016) by Jenniger Elig. Plus, as if flying pigs weren't extraordinary enough

already, there is also Herbert the Flying Blue Pig (2015) by Loveleen

Bahl.

John

Steinbeck's famous Pigasus emblem (© owner presently unknown to me despite

making considerable searches online; reproduced here on a strictly educational,

non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Moreover, the

celebrated American novelist John Steinbeck designed a small winged pig emblem

that he too dubbed Pigasus, its origin stemming from a dismissive comment made

to him long ago by his college professor who was sceptical about his claims

that one day he would become a famous writer, replying sarcastically that this

would happen only when pigs flew. Consequently, once Steinbeck did achieve

fame, he made a point of inscribing Pigasus's image in his books as a personal

insignia, along with the cod Latin phrase "Ad astra per alia porci",

which he intended to mean "To the stars on the wings of a pig", but which

actually translates more closely as "To the stars through other pigs".

(Incidentally,

history also records a non-winged Pigasus of note – a 145-lb domestic pig of

that name that was nominated for President of the USA on 23 August 1968 by an

anti-establishment and countercultural revolutionary group known as the Youth

International Party – but that, as they say, is another story entirely.)

Beautiful wooden winged pig mobile from Bali, which traditionally serves as a spirit chaser (photo appears in uncredited form on numerous websites but its original source is currently unknown to me despite my having made considerable searches - reproduced here on a strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use basis only)

Based upon the traditional folk belief that they will keep evil spirits at bay while a person is sleeping, chasing them far away, in Bali and certain other Indonesian islands wooden mobiles, intricately carved and beautifully painted in bright colours, are often hung above beds. Equally popular today as exotic souvenirs, these eyecatching mobiles frequently take the form of various familiar animals, but sporting a pair of large detachable wings. Amid my own eclectic menagerie of monsters, mystery beasts, and all manner of magical creatures, I have a Balinese winged toad mobile (click here) and also a Balinese winged elephant mobile (click here), but recently I spotted online a photograph (original source unknown) of an exquisite porcine version, resplendent in crimson and gold, and I have since seen photos of others too, in an array of different colours and styles of carving, so the pig is presumably deemed in Indonesia to be a successful spirit chaser.

Last but

definitely not least: here is my very own Pigasus, a small but sweet figurine ornament

that I purchased from some collector's/bric-a-brac fair many years ago, but

which bears no manufacturer's label or identifying details of any kind, so I

have no idea of his origin or history. Consequently, if anyone reading this chapter

could provide me with any details, I'd be very greatly appreciative. After all,

it's not every day that I purchase a pig with wings, so when I do I'd certainly

like to know something about him!

My

very own Pigasus – provenance and production details currently unknown (© Dr

Karl Shuker)