Steller's sea-cows (© William

Rebsamen)

Dr Georg Wilhelm Steller was a German

physician and naturalist participating during the early 1740s in the last of

Danish explorer Vitus Bering's Russian expeditions to the Arctic waters (now

called the Bering Sea) separating Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula from Alaska.

During this expedition, Steller documented many new species of animal,

including four very contentious forms that continue to arouse cryptozoological

curiosity even today. I have already documented one of these, Steller's

sea-bear, on ShukerNature (click here),

so here now are the other three.

SURVIVING SEA-COWS?

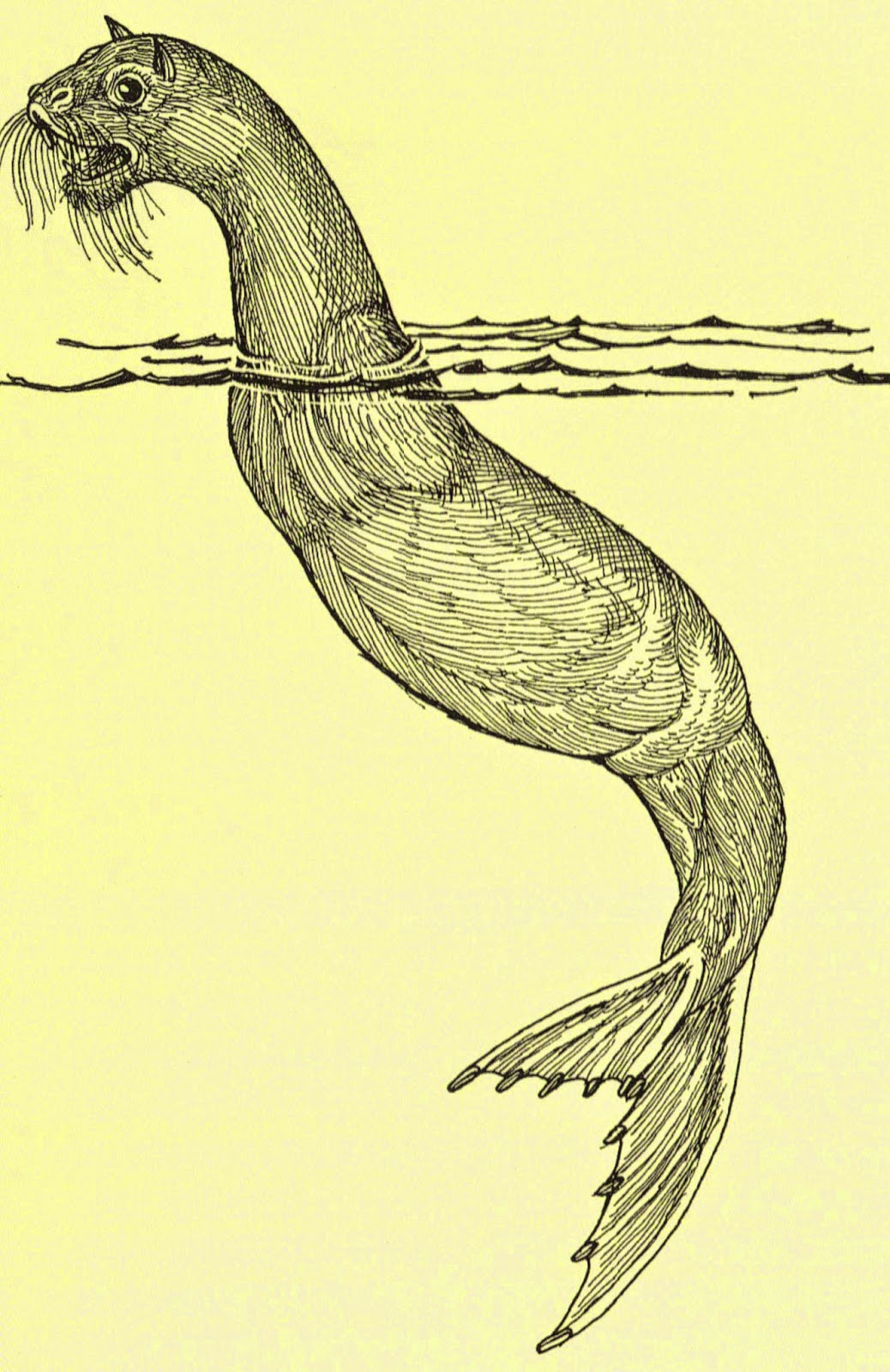

Distantly related to elephants, the

manatees and dugongs are herbivorous aquatic mammals known as sirenians, with

fish-like tails, no hind limbs, and flippers for forelimbs. Nowadays, the

largest living sirenian is the Caribbean manatee Trichechus manatus,

which is up to 15

ft long, but there was once a much bigger

species, called Steller's sea-cow Hydrodamalis gigas (=Rhytina

stelleri). Measuring up to 30

ft long and weighing several tons, this

gigantic sea mammal was discovered in 1741 in

the shallow waters around Copper

Island

and nearby Bering

Island

- named after Vitus Bering, whose expedition was virtually wrecked here that

year. While marooned on this island, Steller studied the sea-cows (the only

scientist ever to do so), which existed in great numbers, but the other sailors

slaughtered them for food.

When he returned to Kamchatka

with news of this enormous but inoffensive species, it became such a

greatly-desired source of meat for future sea travellers that by 1768 - just 27

years after Steller had first discovered it - every single sea-cow appeared to

have been killed. Not one could be found alive, and since then science has

classified this species as extinct. Every so often, however, sailors and other

maritime voyagers journeying through the icy waters formerly frequented by

Steller's sea-cow have spied extremely large, unidentified creatures closely

resembling this officially vanished, giant sirenian.

In 1879, while exploring the polar waters

traversed more than a century earlier by Steller, Swedish naturalist Baron Erik

Nordenskjöld visited Bering Island in his vessel, Vega. He was startled

to learn from one islander, Pitr Vasilijef Burdukovskij, that for the first 2-3

years after his father had settled here from mainland Russia

in 1777, sea-cows were still being seen - and were still being killed, to use

their tough hides for making baydars (native boats).

Even more intriguing was the testimony of

two other islanders, Feodor Mertchenin and Nicanor Stepnoff, who claimed that

as recently as 1854, they had encountered on the eastern side of Bering Island

a very large sea mammal wholly unfamiliar to them - which had brown skin, no

dorsal fin, small forefeet, and a very thick forebody that tapered further

back. It blew out air, but through its large mouth instead of through

blow-holes like a whale, and about 15

ft of its body's length rose above the water

surface as it moved.

Nordenskjöld was sure that they had seen a

Steller's sea-cow, because their description contained details of sea-cow

morphology given in Steller's documented account, which they had never seen.

However, when Stepnoff was later interviewed by American researcher Leonhard

Stejneger, he concluded that the creature encountered by them had actually been

a female narwhal Monodon monoceros (that famous species of toothed whale

whose males characteristically possess a single long spiralled tusk, once

believed to be the unicorn's horn). Stejneger also felt that Nordenskjöld had

misunderstood Burdukovskij's statement regarding when his father had settled on

Bering

Island,

and considered that the correct date was 1774, not 1777.

In 1911-1913, a

fisherman claimed to have seen a dead Steller's sea-cow, brought in by the sea

current towards the Cape

of Chaplin

on Siberia's

easternmost tip, close to the Bering Strait.

Frustratingly, this potentially sensational discovery was never investigated.

Perhaps the most compelling sighting

occurred in July 1962 near Cape

Navarin,

south of the Gulf

of Anadyr,

lying northeast of Kamchatka's

coast. Six strange animals were spied in shallow water by the crew of the

whaling ship Buran about 300

ft away. They were said to be 20-26 ft long, with dark skin,

an upper lip split into two sections, a relatively small head clearly

delineated from its body, and a sharply-fringed tail. Scientists postulated

that these animals must have been female narwhals. However, the description

provided by the Buran whalers fits Steller's sea-cow more closely than a

female narwhal, and it seems unlikely that experienced whalers would fail to

recognise such a familiar creature.

In summer 1976, some salmon factory workers

at Anapkinskaya Bay, just south of Cape Navarin, reported seeing, and actually

touching, the carcase of a stranded sea-cow. One of them, Ivan Nikiforovich

Chechulin, was interviewed by Vladimir Malukovich from the Kamchatka Museum of

Local Lore, and stated that the mysterious animal had very dark skin, flippers,

and a forked tail. Reaching out to touch this creature, they had noticed that

it also had a prominent snout. When Malukovich showed Chechulin various

pictures of sea creatures to assist him in identifying what he and his

colleagues had seen, the creature whose picture he selected as corresponding

with their mystery beast was Steller's sea-cow.

In the late 1970s, British explorer Derek

Hutchinson launched an expedition to search for sea-cows off the Aleutian

Islands, as did Soviet physicist Dr Anatoly

Shkunkov in the early 1980s off Kamchatka.

Neither met with success. Even so, as speculated by cryptozoologists such as

Professor Roy P. Mackal in his book Searching For Hidden Animals (1980),

and Michel Raynal (INFO Journal, February 1987), some sea-cows may have

avoided annihilation by moving away from their former haunts, into more remote

regions - of which the freezing waters and bleak coastlines around Kamchatka,

the Aleutians, and elsewhere in this daunting polar wilderness are plentifully

supplied yet extremely difficult to explore satisfactorily.

STELLER'S SEA-RAVEN – UNMASKED BUT

UNRECOGNISED?

Whereas Steller's sea-cow, even if indeed

extinct today, has been extensively documented and is physically represented in

museums by skeletal material, we still have next to nothing on file (let alone

in the flesh) concerning Steller's most cryptic avian discovery.

While shipwrecked on Bering Island during

1741-42, Steller briefly referred in his journal to a mystifying species that

he called a "white sea-raven" - a rare bird "...not seen in the

Siberian coast...[and which is] impossible to reach because it only alights

singly on the cliffs facing the sea". However, this species has never been

formally identified; nor does it appear to have been reported again by anyone

else. So what could it be?

Seeking an answer to this baffling riddle,

I communicated in June 1998 with cryptozoological enthusiast Chris Orrick, who

has made a special study of Steller's own publications and other

Steller-related works. Chris speculated that Steller's white sea-raven may

actually be some species that is known to science today, but was unknown at

least to Europeans back in the early 1740s - possibly a species native to the Aleutians

but rarely if ever seen around Kamchatka.

One candidate offered by Chris was the surfbird Aphriza virgata, a

white-plumaged wader from Alaska

and America's

western Pacific that may not have been familiar to Steller.

Danish cryptozoologist Lars Thomas from Copenhagen's

Zoological

Museum

was also intrigued by the mystery of the white sea-raven's identity, and he has

offered me his own opinion regarding it. Steller was German, and Lars pointed

out that cormorants are referred to in German as sea-ravens. Indeed, a hitherto

unknown species of cormorant, the now-extinct spectacled cormorant Phalacrocorax

perspicillatus, discovered by Steller during this same expedition, was

referred to by him as a sea-raven.

Consequently, Lars argued that Steller's

mention of a white sea-raven may in reality refer to a white cormorant (either

an albino or a young specimen, as some juveniles are much paler than their

dark-plumed adults).

Alternatively, it may be a bird that

superficially resembles a white cormorant, such as the pigeon guillemot

Cepphus columba in winter plumage, or possibly even a vagrant gannet or

booby.

During our communications, Chris revealed

that in a letter to the Russian

Academy,

dated 16 November

1742, Steller announced that he had prepared

and sent two scientific papers - one dealing with North American birds and

fishes, the other with Bering

Island's

birds and fishes. In view of Steller's meticulous manner of documentation, it

is likely that the latter paper would have contained a detailed description of

the white sea-raven. Unfortunately, however, neither of these manuscripts is

known today, but they may still exist, albeit possibly unrecognised, amid the

Academy's vast archives in St Petersburg.

Unless these or other additional 18th

Century documents on this incognito seabird are uncovered, however, its

identity will probably never be exposed. Ironically, as Chris noted, we may

already know what Steller's sea-raven is, but without realising that we know!

THE MANDARIN-WHISKERED SEA-MONKEYS OF

STELLER AND SMEETON

None of the many creatures documented by

Steller, however, is as curious, or controversial, as the bizarre animal

observed by him for over 2 hours during the afternoon of 10 August 1741,

at approximately 52.5°N

latitude, 155°W

longitude. He described it as follows:

It was about two Russian

ells [about 5 ft] in length; the head was like a dog's, with pointed erect

ears. From the upper and lower lips on both sides whiskers hung down which made

it look almost like a Chinaman. The eyes were large; the body was longish round

and thick, tapering gradually towards the tail. The skin seemed thickly covered

with hair, of a gray color on the back, but reddish white on the belly; in the

water, however, the whole animal appeared entirely reddish and cow-colored. The

tail was divided into two fins, of which the upper, as in the case of sharks,

was twice as large as the lower. Nothing struck me more surprising than the

fact that neither forefeet as in the marine amphibians nor, in their stead,

fins were to be seen...For over two hours it swam around our ship, looking, as

with admiration, first at the one and then at the other of us. At times it came

so near to the ship that it could have been touched with a pole, but as soon as

anybody stirred it moved away a little further. It could raise itself one-third

of its length out of the water exactly like a man, and sometimes it remained in

this position for several minutes. After it had observed us for about half an

hour, it shot like an arrow under our vessel and came up again on the other

side; shortly after, it dived again and reappeared in the old place; and in

this way it dived perhaps thirty times.

After watching this extraordinary creature

frolicking comically in the water with a long strand of seaweed for a time,

Steller, greatly desiring to procure their strange sea visitor in order to

prepare a detailed description, loaded his gun and fired two shots at it.

Happily, the animal was not harmed, and swam away, though they saw it (or

another of its kind) on several subsequent occasions in different stretches of

the sea.

No known species corresponds with Steller's

description of this peculiar beast, which became known as Steller's sea-monkey

or sea-ape. Moreover, until fairly recently, no further sighting of such a

creature had ever been reported either, leading scientists to speculate that

whatever it had been, its species must surely now be extinct. On a clear

afternoon in June 1965, however, eminent British yachtsman-adventurer Brigadier

Miles Smeeton was sailing by the central Aleutian

Islands aboard his 46-ft ketch Tzu Hang,

with his wife, daughter, and a friend aboard, when he and the others sighted a

remarkable sea-beast.

As since documented by explorer-journalist

Miles Clark (BBC Wildlife, January 1987), lying in the water close off

the port bow was what seemed to be a 5-ft-long animal with 4-5-in-long

reddish-yellow hair, and a head more dog-like than seal-like, whose dark

intelligent eyes were placed close together, rather than set laterally on the

head like a seal's. Indeed, Henry Combe, the Smeetons' friend aboard their

ketch, stated that it had a face rather like a Tibetan shih-tzu terrier

"...with drooping Chinese whiskers". As the vessel drew nearer, this

maritime mandarin "...made a slow undulating dive and disappeared beneath

the ship". No-one spied any limbs or fins. Their observation of it had

lasted 10-15 seconds, and they have remained convinced that it was not a seal.

Although sea otters occur in these waters, this creature did not resemble any

sea otter previously spied by them either.

Conversely, it closely corresponds with

Steller's description over two centuries earlier of his mystifying sea-monkey,

thereby giving cryptozoologists hope that its species still exists. As for its

identity, however, there is still no satisfactory explanation. Its inquisitive,

playful, intelligent, supremely agile behaviour are all characteristics of

seals and otters, yet Smeeton and his fellow observers are convinced that their

creature was neither of these, and it certainly does not bear any immediate

resemblance to such animals - set apart by its apparent absence of forelimbs,

its asymmetrical vertical tail, and its mandarin-style whiskers. Equally, it

seems highly improbable that any wildlife observer as experienced and as

meticulously accurate in chronicling his observations afterwards as Steller

would fail to recognise it as a type of seal or otter if this is truly all that

it was. In fact, Steller was so perplexed by the creature that he made no

attempt whatsoever to classify it.

Via independent lines of research, Chris Orrick

and Jay Ellis Ransom, formerly executive director of the Aleutian-Bering Sea

Expeditions Research Library in Oregon, have both formulated theories that

Steller's sea-monkey may have been a vagrant specimen of the Hawaiian monk seal

Monachus schauinslandi - one that had wandered north far from its normal

Hawaiian archipelago domain. Chris also suggests that it may have been

undergoing its annual moult at the time, explaining its fur's appearance as

documented by Steller. Nevertheless, it still requires an appreciable stretch

of the imagination to convert the sea-monkeys described here into any form of

seal, Hawaiian monk or otherwise.

Perhaps one day a zoologist voyaging in the

Bering Sea will espy Steller's

most enigmatic discovery, which seems still to survive in these frigid waters,

and in so doing may finally resolve a fascinating zoological mystery that has

persisted for more than 250 years.