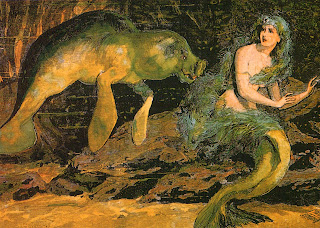

The mermaid of Haraldskaer's

skeleton, exhibited at the Danish National Museum, Copenhagen, in 2012 (© Danish National Museum –

reproduced here on a strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use basis, for

review purposes only)

Only a few days after watching, and greatly

enjoying, Guillermo del Toro's wonderful fantasy movie The Shape of Water,

concerning a captured amphibious humanoid (click here

to read my review of it), earlier today I was asked on Facebook whether I knew

anything about the subject of a striking photograph currently doing the rounds on

social media sites, including the Fortean Times Appreciation Group on FB.

Happily, I knew quite a lot about it, so here is the remarkable history of the

mermaid of Haraldskaer.

The photograph in question is the one that opens

this present ShukerNature blog article of mine, and shows what seems on first

sight to be the skeleton of a mermaid. The photo had been shared on the Fortean

Times Appreciation FB group from another such group, Pictures in History, where

some brief details of its supposed origin and nature had been provided, and

which are as follows.

Allegedly, this skeleton is that of a mermaid that

had been found at Haraldskaer in mainland Denmark by a farmer while ploughing his field. And

according to a more detailed description presented alongside it at the Danish

National Museum in Copenhagen where the mermaid of Haraldskaer was first displayed, in 2012, it was about 18 years old, with long thick hair and long sharp

canines, and also had a purse that contained a shark's tooth, a snake's tail, a

mussel shell, and a flower (just like any self-respecting mermaid would be

expected to keep inside her purse). Its species is claimed to be Hydronymphus

pesci, believed extinct since the end of the 17th Century, and apart

from a missing left hand the skeleton is complete, much more so than the only

other known H. pesci skeleton, apparently held at the Hermitage Museum in St

Petersburg, Russia, which lacks a tail. Moreover, this species is

believed to belong to the Asian lineage of merfolk, thereby making the finding of

specimens in Europe especially rare.

Close-up of the tail of the

Haraldskaer mermaid skeleton (© Danish National Museum – reproduced here on a

strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use basis, for review purposes only)

Altogether a fascinating history, but, needless to

say, entirely fictitious. In fact, as Danish zoologist and cryptozoological researcher Lars Thomas has kindly informed me, the Haraldskaer mermaid skeleton, complete with shark-inspired tail, was manufactured by Mille Rude, a Danish artist, for a special exhibition staged at the Danish National Museum, Copenhagen, during 2012. Rude took her inspiration from the very famous real discovery in 1835 of Haraldskaer Woman - the naturally-preserved body of a young woman found in Haraldskaer Bog, and dating back to approximately 490 BC (pre-Roman Iron Age).

In 2013, the mermaid skeleton was displayed at the Art Museum in Vejle on the east coast of the Jutland peninsula, constituting western Denmark, and a year later it was aptly exhibited in the manatee enclosure at Odense Zoo in central Denmark (manatees are popularly deemed to be the inspiration for mermaid sightings). In 2016, its perambulations took it to the Maritime Museum in Elsinore, Denmark, where it remains on display today. So far, so straightforward, but this is cryptozoology, albeit featuring in this instance an unequivocal cryptozoological gaff (an artificially constructed specimen). Consequently, nothing is ever that straightforward, as will be revealed a little later here.

In 2013, the mermaid skeleton was displayed at the Art Museum in Vejle on the east coast of the Jutland peninsula, constituting western Denmark, and a year later it was aptly exhibited in the manatee enclosure at Odense Zoo in central Denmark (manatees are popularly deemed to be the inspiration for mermaid sightings). In 2016, its perambulations took it to the Maritime Museum in Elsinore, Denmark, where it remains on display today. So far, so straightforward, but this is cryptozoology, albeit featuring in this instance an unequivocal cryptozoological gaff (an artificially constructed specimen). Consequently, nothing is ever that straightforward, as will be revealed a little later here.

Humorous 19th-Century illustration of a beautiful mermaid clearly less than impressed by the decidedly homely appearance of her supposed real-life inspiration, a manatee (public domain)

Meanwhile: One of the most famous tourist attractions in Denmark is Erik Eriksen's charming bronze statue of the

eponymous character in Hans Christian Andersen's delightful 1837 fairytale The

Little Mermaid. Eriksen's sculpture, measuring just 50 in high and weighing 385 lb, was officially unveiled on 23 August 1913, residing on permanent display thereafter upon a

rock at the edge of Copenhagen's harbour. Since then, it has been visited, posed

alongside, and photographed by millions of tourists from all over the world, including

my mother and myself back in 1979, and is officially classed as a National

Treasure of Denmark

For much of 2010, however, this fish-tailed icon was

temporarily absent from her accustomed site at the harbour side when she

starred instead in the Danish Pavilion at the 2010 World Expo, held in Shanghai,

China, remaining there from late March to 20 November. So forlorn and forsaken

was the rocky prominence upon which she had sat for generations, gazing wistfully

across the waters, however, that a plan, or, to be precise, a prank, was

hatched to replace her there, if only for a very short time, but with something

equally fishy – in every sense.

And so it was that on Maundy Thursday 2010, the skeleton of a mermaid duly appeared in the statue's stead,

sitting in a similar pose on a plaster replica of her rock but placed very near to hers, and heralded with the somewhat macabre

announcement to the media that the Little Mermaid had returned. After residing

there for two hours, during which time it had attracted considerable attention

and photo-snapping from locals and tourists alike, the skeleton was removed (to ensure that the fickle Danish weather did not damage it) and

taken to the Natural History Museum of Denmark, in Copenhagen, where it was on public display throughout

the Easter holiday period. But what is the true nature of this very

striking specimen?

It is, of course, another gaff – this time consisting of a human skeleton down to and including its hips, plus

the tail of a swordfish Xiphias gladius. Its creation and the prank of

placing it briefly on show at the harbour during the Little Mermaid's Chinese leave

of absence was the brainchild of Hanne

Strager, at that time the head of exhibitions at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, in

Copenhagen, and it certainly attracted immense interest – and not just in spring

2010. It had actually been created a few years earlier at the museum, to feature in an exhibition there devoted to legendary creatures, and had been specifically structured to mimic the pose adopted by the Little Mermaid statue. But what has any of this to do with the Haraldskaer mermaid skeleton? I'm glad that you asked.

The Natural History Museum of Denmark's

mermaid skeleton gaff, posed upon a plaster replica of the Little Mermaid statue's rock (© Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen – reproduced here on a strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use

basis, for review purposes only)

Photographs of the Haraldskaer mermaid skeleton

have been circulating widely online for some years, and far more so, unfortunately,

than the facts behind them, so that these pictures have incited (and continue

to incite) much speculation as to whether the skeleton is actually genuine. Not

only that, in an all-too-familiar trend seen on the Net with unusual images,

they have even inspired various entirely new, but equally fictitious histories

for it.

Consequently, I have seen some sites claiming that

the skeleton has been the subject of much controversy since being discovered in

Poland(!), and even in Indonesia – one site affirming that it had been discovered in

Surabaya, on the island of Java. Worst of all, however, is that all of the media reports that I have read concerning it, even those from ostensibly respectable sources, have either been incomplete or decidedly ambiguous, inasmuch as they have implied that the Haraldskaer mermaid skeleton (created by Rude) and the mermaid skeleton placed briefly on the plaster replica of the Little Mermaid statue's rock (and whose creation was overseen by Strager) are one and the same, when in reality they are entirely different, albeit extremely similar specimens. Hence I wish to thank Lars Thomas most sincerely for revealing to me the true situation, and thereby assisting me to bring to a close the exceedingly curious and hitherto highly-confused case of the two mermaid skeletons, and also to Richard S. White and Markus Bühler for arousing my suspicions regarding the online sources consulted by me when originally preparing this blog article. Indeed, it now means that this article of mine may well be the only account presently online that provides an accurate, non-conflated coverage of these two gaffs.

A popular expression is that you can't keep a good

man (or woman) down. Neither, it would seem, can you keep a good mermaid (or two) down;

nor, at the risk of mixing metaphors further, can the internet let

sleeping mermaids lie – not even ones that never existed to begin with!

Today I learned that Dr. Seuss (Theodore Seuss Giesel) liked to make gaffs. :) He called them "unorthodox taxidermy", though he used more papier mache than dermis. (Is that a consideration with gaffs?) His father worked at a zoo, and would send him antlers and parts from dead animals. He would combine these with papier mache and paint to make creatures just as imaginative as his illustrations but with much more interesting surface textures.

ReplyDeleteInteresting! I'll have to see if I can track down any photos of his gaffs.

DeleteIs the skeleton true

ReplyDeleteNo - as I state in my aboev article, it is a manufactured fake.

DeleteInteresting

ReplyDelete