Photograph from c.1870 depicting a very spectacular horned horse

HORSES WITH HORNS

During the 19th Century, eminent French zoologist Baron Georges

Cuvier loftily denounced that most mystical and magical of legendary beasts,

the unicorn, as a zoological impossibility - claiming that a single median horn

could never arise and develop from the paired frontal (brow) bones of a mammal's skull.

Since Cuvier's damning pronouncement, the unicorn has received short shrift

from science. Yet this attitude may be both unjust and unjustified.

To begin with: in 1934, Maine University biologist Dr William

Franklin Dove successfully, and spectacularly, refuted Cuvier's claim

concerning the growth of a single median horn from the frontal bones - by

creating a bovine unicorn. He achieved this remarkable feat by removing the

embryonic horn buds from a day-old Ayrshire bull calf, trimming their edges

flat, then transplanting them side by side onto the centre of the calf's brow.

Growing in close contact with one another, the transplanted buds yielded a

massive single horn, which proved so successful a weapon that its owner soon

became the undisputed leader of an entire herd of cattle. Yet despite his

dominance, this unicorn bull was a very placid beast, thus resembling the

legendary unicorn not only morphologically but also behaviourally. Just a

coincidence?

Some researchers have since speculated that perhaps ancient

people knew of this simple technique, and had created single-horned herd

leaders, whose imposing appearance and noble temperament thereafter became

incorporated into the evolving unicorn legend.

Thus, the development of a single median horn is not an

impossibility after all - at least not in cattle, that is. Horses, however,

must surely be a very different matter, bearing in mind that they do not even

grow paired horns (let alone median ones) - or do they?

In fact, records of horses with horns, though rare, are by no

means unknown. In 1929, for instance, German zoologists P.P. Winogradow and

A.L. Frolow published a short account within the journal Anatomische

Anzeiger concerning a horse that had exhibited lateral horn development on

its brow, accompanied by a photograph of the horse's skull.

Moreover, in an American Museum Novitates paper of 17 August 1934, S. Harmsted Chubb documented several

horses each exhibiting a small pair of lateral skin-ensheathed frontal protuberances

just above the eyes. In the photos of some such horses contained in Chubb's paper,

however, these 'horns' can be seen to be tightly pressed against the side of

the horse's skull, not projecting outward, away from the skull.

Far more intriguing, conversely, is the following excerpt, from

South American explorer Felix de Azara's Natural History of the Quadrupeds

of Paraguay and the River La Plata (1837):

I have heard for a fact, that, a

short time ago, a horse was born in Santa Fé de la Vera Cruz, which had two

horns like a bull, four inches long, sharp and erect, growing close to the

ears; and that another from Chili was brought to Don John Augustin Videla, a

native of Buenos Ayres [sic], with strong horns, three inches high. This horse,

they tell me, was remarkably gentle; but, when offended, he attacked like a

bull. Videla sent the horse to some of his relatives in Mendoza, who gave it to

an inhabitant of Cordova in Tucuman, who intended, as it was a stallion, to

endeavour to form a race of horned horses. I am not aware of the results, which

may probably have been favorable.

Thus, if horses can occasionally develop paired frontal horns

and a median horn can be induced to grow from the frontal bones of cattle, then

surely in this unrivalled age of biological modification, where sophisticated

techniques yielding cloned, transgenic, and other man-made life forms are

already commonplace, it would not be difficult to conduct a slightly modified

version of Dove's experiments - using equine-derived horn (or horn-substitute)

tissue, and a foal, instead of a calf, as the recipient?

Engineering a genuine equine unicorn would make a fascinating

project for any zoological team capable of ignoring the sound of Cuvier turning

loudly in his grave. After all, it isn't every day that science is granted the

opportunity to create a living legend.

But if that is what constitutes a horse with horns, what, then,

is a horned horse? I'm glad you asked!

HORNED HORSES

One of the most frequently reported and familiar of

teratological conditions exhibited by humans is the possession of extra fingers

and/or toes - polydactyly. However, this genetically-induced phenomenon has

also been widely recorded among many domestic animals (e.g. dogs, cats, horses,

pigs, chickens, pet rats and mice, guineapigs), as well as from wild species as

diverse as bats, salamanders, leopards, llamas, and even the Malaysian flying

lemur. Moreover, it can take several different forms, each under the control of

a different mutant allele (gene form).

Probably the most famous non-human examples of extra-toed

mammals can be found among the records of polydactylous horses. One of the

classic examples of evolution is the gradual disappearance over millions of

years of all but one of the horse's functional toes. The horse lineage began

with the Eocene epoch's 'dawn horse' Hyracotherium (formerly called Eohippus),

with four functional toes on each forefoot; leading on to Mesohippus of

the Oligocene epoch, with three toes; to Merychippus of the Miocene, in

which the two lateral toes were greatly reduced in size so that they no longer

touched the ground; and to Pliohippus of the Pliocene, whose two lateral

toes were merely insignificant splints whereas its central toe was massively

enlarged, with its single hoof (modified toenail) bearing the animal's entire

body weight. This same condition is present in normal specimens of all

modern-day horses too, belonging to the genus Equus. (It should be

noted, however, that this is not a direct, straight-line evolutionary series, one

genus leading directly to the next, even though it is commonly if erroneously presented

as such, because several other genera of horses also appeared and disappeared during

equine evolution, exhibiting varying numbers of toes.)

Nevertheless, the teratological literature contains numerous

well-documented cases of abnormal modern-day horses (notably of the Shire horse

breed) that possess one or more well-developed lateral toes, often bearing

their own hooves and sometimes even touching the ground alongside the normal,

massive central toe's hoof - as if determined to reverse the course of their

own evolution! The spontaneous occurrence in an individual of a trait like this that constitutes an evolutionary throwback is known as atavism.

One such horse was an extraordinary 19th-Century specimen

from Texas, which possessed a pair of

well-developed lateral toes on each hind foot, curving downwards on either side

of the central one like horns - as a result of which this specimen became known

as the horned horse. In contrast, only one such toe, positioned on the central

toe's inner side, was present on each forefoot. It was from this specimen that

other polydactylous horses also became known as horned horses, a term used in

particular with specimens exhibited in sideshows, carnivals, circuses, etc.

These very distinctive-looking horses have a long history, and

include among their number a renowned steed of Julius Caesar. According to

Suetonius in de Vita Caesaria (vol. LXVI):

[Caesar] used to ride a remarkable

horse, which had feet that were almost human, the hoofs being cleft like toes.

It was born in his own stables, and as the soothsayers declared that it showed

the owner would be lord of the world, he reared it with great care, and was the

first to mount it; it would allow no other rider.

This account and many others were included within a major paper

on the subject by Prof. Othniel C. Marsh, published during April 1892 in the American

Journal of Science. As Marsh noted, the extent of polydactyly exhibited by

horses varies greatly. Some such specimens merely exhibit a small extra toe (often

barely visible externally) on the inner side of one or both forefeet. In more

notable cases, two such toes, one on each side of the normal central toe, may

be present, plus one or a comparable pair on one or both hind feet (although

these latter are usually smaller than their counterparts on the forefeet). In

much rarer cases, however, these various supernumerary toes may be much more

highly developed, to the extent that the affected feet compare favourably with

the normal feet of the Miocene horse Merychippus, and even occasionally

with the Oligocene's Mesohippus. Most dramatic of all are the extremely

rare examples that not only mirror the Mesohippus condition but also

possess a tiny fourth toe, representing the ancestral pollex (thumb) or hallux

(big toe).

The most celebrated example of this last-mentioned and very

extreme equine polydactylous state is the so-called 'six-footed' horse owned by

Theodore F. Wood of New Jersey and named

Clique, who was exhibited at shows for many years in the U.S.A. and elsewhere. Clique

died at an advanced age in January 1891, whereupon his owner presented his body

to Prof. Marsh for the Yale Museum. Marsh observed

that whereas his hind feet were basically normal, each of Clique's forefeet

sported a well-developed toe on the central toe's inner side. For much of its

length, this extra toe was separate from the central toe, bore its own long

hoof, and actually made contact with the ground, so that each forefoot appeared

double. This explained Clique's 'six-footed' appellation, because on first

sight he seemed to possess two hind feet and four forefeet. In addition, close

observations revealed that another supernumerary toe was represented by a

splint-like structure on the outer side of the central toe on each of Clique's

forefeet, whereas just under the skin in the locality of the ancestral pollex a

similar splint could be felt that corresponded to a fourth toe!

Even more remarkable than Clique, however, though less famous,

was a so-called 'eight-footed' Cuban horse depicted in Marsh's paper and

reproduced below here in the present ShukerNature post, which gained its name

from the fact that all four of its feet each bore a well-developed second toe

on the inner side of the normal central toe, one again bearing its own hoof and

making contact with the ground alongside the latter.

This horse, a male, was on exhibition in New Orleans during

spring 1878, and it was Dr Sanford E. Chaillé from that city who drew Prof. Marsh's

attention to it. The horse was subsequently brought to the North, and a few

days later was displayed at New Haven, Connecticut, where Marsh closely examined

it.

As with the occasional reappearance of dew-claws on the hind

feet of dogs, polydactyly in horses involves the redevelopment of toes normally

absent in modern-day species but present in ancestral ones (rather than simply

involving the duplication of existing toes, as occurring, for example, in

polydactylous humans and cats). A plausible explanation for this type of

polydactyly is that during the evolution of the horse, the genes responsible

for the formation of all toes other than the central one became increasingly

repressed by other genes, whereas those responsible for the central toe

actually intensified their activity, so that eventually the latter was the only

toe that was 'permitted' to form. Applying this theory to modern-day

polydactylous horses, it could be argued that during their embryonic

development something goes wrong with the repression mechanism acting upon the

genes responsible for the formation of those ancestral toes, so that it fails

to operate, with the result that these ostensibly 'lost' toes reappear - conjured

forth as if by magic from their prehistoric past.

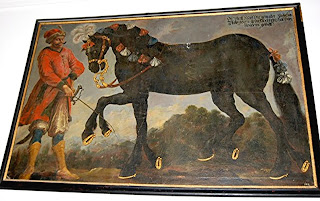

Painting of the supposed eight-footed

horse owned by Mark Sittich von Hohenems, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg (©

Curious Expeditions/Flickr)

According to a very beautiful colour painting

portraying it (above), a bona fide eight-footed horse (i.e. one that possessed

two entirely separate feet on each leg, not just supernumerary toes) was owned

by Mark Sittich von Hohenems, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg (1574-1619), who

was renowed for his collection of rare and unusual animals. The horse had been

obtained in Arabia, each of its alleged eight feet possessed its own horseshoe

in the painting, and the painting itself is on public display at the Palace Helbrunn

(now a museum), situated between Salzburg and Untersberg, Austria. Whether or

not the horse was truly eight-footed, however, or whether the painting is merely

a very imaginative depiction of a horned horse comparable to the Cuban specimen

documented earlier here, is unknown.

Whenever talking about eight-footed horses, one cannot help but

be tempted to think of Norse mythology and Odin's famous eight-footed steed,

Sleipnir – but there was one fundamental difference between Sleipnir and the

horned horses documented here. Not only did Sleipnir have eight fully-formed

feet (not just extra toes that looked a little like extra feet), he also had

eight legs!

One last

comment, just to add a further level of confusion to horses with horns and horned

horses: sometimes, again most especially in sideshows, circuses, and suchlike,

'horned horse' is a term that has been applied to a gnu or wildebeest – this large

African antelope (which actually constitutes two very closely-related species) does

look superficially equine but possesses a pair of very noticeable horns.

A

white-tailed (aka black) gnu Connochaetes gnou, one of two antelopine 'horned

horses' (public domain)

"Photograph from c.1870 depicting a very spectacular horned horse"

ReplyDeleteThere's me thinkin' it was Lady Gaga wearin' four pairs of platty boots at the same time [if my daughter sees this she'll kill me]!

I was go'n'o crack a terrible joke about the impossibility of geldings gettin' the horn but in the end I decided that'd be eunuch corn...

Haha!

In an old guide to the Natural History Museum in London was mention of two skulls of horses with horns. It was commented on as odd because no fossil horses had horns. But maybe the skulls were destroyed during the Blitz..

ReplyDeleteFame is a strange thing, perhaps especially in the Internet era. I was surprised to see polydactyly described as "most famously in horses," when I'd never heard of it in horses before. ;) Just a quirk of information transmission, I guess.

ReplyDeleteI don't quite understand the modern love for unicorns. I recall it first described to me as a creature untameable except by a maiden, which suggests a symbolic origin I'm not too sure I want to know too much about, LOL! Perhaps it is one of the nicer ancient legends on that sort of topic.