Tom the water-baby meeting the last of

the great auks or garefowl – an exquisite painting by Warwick Goble for an illustrated

1909 edition of Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies, which is one of my all-time favourite children's novels (public domain)

And there he saw the last of the Gairfowl, standing up on the Allalonestone, all alone. And a very grand old lady she was, full three feet high, and bolt upright, like some old Highland chieftainess. She had on a black velvet gown, and a white pinner and apron, and a very high bridge to her nose (which is a sure mark of high breeding), and a large pair of white spectacles on it, which made her look rather odd: but it was the ancient fashion of her house.

Charles Kingsley – The Water-Babies: A Fairy-Tale For a Land-Baby

As fondly commemorated above in Charles Kingsley's classic children's novel The Water-Babies: A Fairy-Tale For a Land-Baby (1863), one of the most famous extinct species of modern-day bird is the great auk Pinguinus impennis, also known as the garefowl, gairfowl, or geirfugl. Almost 3 ft tall (the only taller auk was the prehistoric Howard's Lucas auk Miomancalla howardi), this sturdy flightless black-and-white seabird from the northern hemisphere was superficially reminiscent of the southern hemisphere’s familiar penguins, but its link with them does not end there – because the great auk was the original penguin, the latter name having been initially bestowed upon this puffin-allied species. Only later was it applied by those European sailors first penetrating Antarctic waters to the wholly-unrelated birds that they encountered there and which retain it today, long after the original northern penguin’s extermination.

The great auk once existed in tens of millions,

nesting on the rocky coastal areas of islands on both sides of the North Atlantic, but it was in America that it first met its end. Its feathers were

prized for use in eider-downs and feather beds, its flesh was tasty and

therefore much sought-after by sailing vessels, and collectors coveted its

eggs, and so this imposing but helpless bird was massacred in countless

numbers. On Funk Island off Newfoundland, for example, its precious nesting grounds were

frequently raided and mercilessly desecrated. Thousands of auks were captured

alive and cooped together in great enclosures like domestic fowl until it was

their time to be slaughtered en masse by being clubbed to death and then thrown

into furnaces, enabling their feathers to be more readily removed from their

bodies. By the second decade of the 19th Century, the great auk was merely a

memory in North America.

In Europe, its major stronghold was the Icelandic coast, but

great auks even existed around the more northerly islands of Scotland, most notably St Kilda but also visiting the

Orkneys, with one particularly famous Orcadian pair being nicknamed the King

and Queen. Sadly, however, they were no safer from hunting here than they had

been in the New World. Moreover, it was especially ironic that as this

species became rarer, it became ever more persecuted by museum collectors -

anxious to add specimens and eggs to their collections before it died out! The

last known pair of great auks constituted a couple that were clubbed to death

(and their egg smashed) on the Icelandic island of Eldey on 3 June 1844, since when the species has long been deemed

extinct (but see below). A particularly moving novel reconstructing this

terrible, shameful event, entitled The Last Great Auk and first

published in 1964, was written by Allan Eckert, and was reviewed by me here

in an earlier ShukerNature post.

The Last Great Auk by Allan Eckert – Collins hardback 1st

edition, 1964 (© Allan Eckert/HarperCollins, reproduced here on a strictly

non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

For some decades thereafter, however, various quite

convincing reports of lone living specimens emerged from various remote

far-northern European localities, and it is with these little-mentioned,

'post-extinction' reports of great auks that this present ShukerNature article

is concerned.

Perhaps the most (in)famous of these is also the

most recent one. On 19 April 1986, London’s Daily

Telegraph carried the remarkable news that an expedition was to set sail

for Papa Westray, a tiny islet in Scotland’s Orkney group, in response to reputed sightings of a

living great auk there. Unhappily for cryptozoology as well as for mainstream

zoology, however, it proved to be more of a canard than an auk! For as

documented in the International Society of Cryptozoology's ISC Newsletter for

spring 1987, it turned out to be nothing more than an imaginative advertising

promotion for a certain brand of whisky, using a robotic auk!

This is not the first false alarm for this long-lost species.

Reports of great auks in the Lofoten Islands, an archipelago off Norway's northwestern coast, emerged every so often during

the late 1930s. When finally investigated, however, the birds proved to be

genuine penguins – namely, nine king penguins Aptenodytes patagonicus, which had been

brought from sub-Antarctica as pets by whalers and had

been released on the Lofotens in August 1936 when no longer wanted. The last

two died there in 1944.

Nevertheless there are a number of more promising reports

of post-1844 survival too. Indeed, a sighting of a single living specimen on the

Grand Banks of Newfoundland in December 1852, made by eminent field naturalist

and ornithologist Colonel Henry Maurice Drummond-Hay with the aid of binoculars,

and at a distance of only 30 yards or so away while he was traveling aboard a steamer, has

lately been formally accepted by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources).

It was first brought to mainstream attention in 1979 by T.R. Halliday in a paper

on the great auk published by the periodical Oceans. Moreover, in 1853 a dead great auk was supposedly found on the shore

of Trinity Bay on Newfoundland's eastern side, and three years later another

one was reputedly caught on its western shore, but neither specimen was

submitted to scientists for confirmation (or otherwise).

Most of the others report, conversely, are buried in

Norwegian journals and newspapers of the 1800s, but a good example from a 19th-Century

English publication was contained in Dr Isaac J. Hayes’s The Land of

Desolation (1871), which describes his adventures in Greenland during summer 1869. The auk-related account concerns a conversation

that Hayes had with a naturalist called Hansen:

The great auk, long since supposed to be entirely extinct, he told me had been recently seen on one of the Whale-fish Islands. Two years before [in 1867] one had been actually captured by a native, who, being very hungry, and wholly ignorant of the great value of the prize he had secured, proceeded at once to eat it, much to the disgust of Mr. Hansen, who did not learn of it until too late to come to the rescue. How little the poor savage thought of the great fortune he had just missed by hastily indulging his appetite!

On 10 November 2004, Dr Alan Gauld of Nottingham, England, kindly brought to my attention the following account.

Published

in the autumn 1929 issue of Bird Notes and News, it was reported by

H.A.A. Dombrain, a manager for an English concern in Norway’s Lofoten Islands. Dombrain noted

that one of his boatmen, a Finn called Jodas, who was an experienced hunter and

amateur naturalist, had told him that earlier that day (presumably the same day

that Gauld wrote his account to Bird Notes and News) he and Dombrain’s

shipwright, a man called Evenson, had seen a bird under the wharf that, in

spite of their experience, they were wholly unable to identify.

Intrigued,

Dombrain showed them separately a series of bird illustrations, including all

of the likely (and unlikely) species that it could be. To his great surprise,

both of them, independently of each other, selected an image of the great auk

as the species that matched their mystery bird.

Prior to its

extinction almost a century earlier, the great auk had indeed inhabited the

wild, sparsely-inhabited coasts of these islands. Moreover, the earlier-noted

release there of sub-Antarctic king penguins was several years after the

sighting of Evenson, so these birds could not explain it. Consequently, is it

possible that he had truly seen a lone, elusive great auk from some small

colony that had somehow persisted beyond their species’ official extinction

date in this remote locality?

Equally

enigmatic is the taxonomic identity of the mysterious Arran auk – the name

given by the elderly pilot of a boat carrying the Reverend G.C. Green around

Scotland's western coast to a strange seabird as large as a goose or turkey and

with a large sharp beak, but with such short wings that it never flew, only

paddled, and was black in colour dorsally, white ventrally. As the Rev. Green noted

in an article by him that was published on 27

March 1880 in The Field magazine, when he showed the pilot an illustrated

book of birds the latter readily identified the picture of a great auk as portraying

the Arran auk. He also stated that it only appeared

on the coast of western Scotland's Isle of Arran in March each year, that he

had shot three specimens, and that he would obtain one for Green the following

March.

Tragically,

however, the pilot, who was an old man, passed away not long after taking Green

in the boat, but his sons vowed that they would obtain a specimen of this bird

in his stead. Sure enough, they did subsequently present Green with what they

claimed to be an Arran auk, but it proved to be merely a great

northern diver Gavia immer (aka the common loon in North America). However,

Green pointed out that their father the pilot had readily distinguished between

divers and the Arran auk when talking with him during their

boat journey, so Green suspected that if he had been alive the pilot would not

have sent him a diver.

A few additional cases of putative post-1844 survival

for the great auk can be found within a short chapter entitled ‘Late Records,

Anomalous Sightings and Cryptozoology’ in Errol Fuller’s definitive book The

Great Auk (1999).

Errol Fuller's authoritative tome The

Great Auk (© Errol Fuller – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial

Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

For example, he notes that in 1971 the famous English

nature-writer and broadcaster J. Wentworth Day recalled how back in 1927 he was

informed by an acquaintance from his youth named Edward Valpy, whom he deemed

to be a first-rate naturalist and explorer of unimpeachable truth, that while spending

some time on one of the Lofotens he had spied a great auk slipping off a rock

near the local boat-builder's yard and quay. Day also stated that when Valpy

had informed the boat-builder of what he had seen, the builder confirmed that

it had been around for some time, that his sons had often seen it, and that

once it had even dived beneath the boat on which he had been sailing. Note

again that this was several years before the king penguins had been

released here, so they cannot explain this report of multiple sightings.

Also of interest

is the much-disputed claim by a Norwegian named Brodtkorb that he had shot a

great auk, one of four supposedly encountered by him one day in April 1848

while he was rowing with some companions in a little strait constituting an arm

of the sea separating Vardö from the islets of Hornö and Renö in Norway. The

four birds were paddling in the water, and continued to do so, not flying away,

even after he had shot one of them. As far as he could remember, its back,

head, and neck were all completely black, except for a white spot at the eye on

the side of the neck. Its wings were extremely small, and in shape it resembled

those familiar auks the razorbills and guillemots.

Sadly, Brodtkorb

threw the dead bird's carcase on the beach when he landed, then later regretted

doing so, but when he returned to the beach the following day to retrieve it,

it had gone, carried away by the tide. Brodtkorb's mystery bird has since been

discounted by various sceptical naturalists as having merely been a diver or

some familiar auk species, but those who knew him personally vouched for his

knowledge of wildlife, stating that if this is really all that it had been, as

an experienced sportsman he would have readily recognised it as such.

Problematically,

as Errol pointed out in his book, Vardö is much further north than any

currently-known locality for great auk occurrence in historical times, but its

remains in prehistoric middens from this region confirm that in earlier ages it

did indeed occur there. Errol's book also contains other post-1844 claimed

sightings of this species in Norwegian and Greenland localities further north

than would be expected, based at least upon its confirmed historical

distribution and irrespective of the sightings' dates.

Might it just be

possible, however, that in such far-north localities, out of the ready reach of

hunters, some few great auks did indeed survive beyond, possibly even well

beyond, their species' official extinction dates (1844/1852) – and might some

even be lingering there today?

It would be a very

bold person indeed to state with any degree of confidence that the great auk is

not a lost auk after all. Then again, it would be a very bold person indeed to attempt

spending the extensive period of time that would be required to seek with any

degree of proficiency this iconic bird in such inhospitable, inaccessible Arctic

terrain. So who can truly say for certain?

Two

famous taxiderm specimens of the great auk: (left) the Leipzig Museum great auk;

and (right) the great auk and replica egg at Kelvingrove, Glasgow (© Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence /

© Mike Pennington/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

Finally: Here is

my two-page review of Errol's superb great auk book that was published in the autumn

2000 issue (#21) of the late Mark Chorvinsky's Strange Magazine (please click its pages to enlarge for reading purposes):

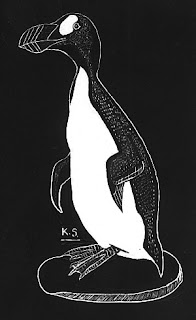

And here is a scraperboard illustration – the very first scraperboard picture that I ever attempted – of a great auk that I prepared more than 30 years ago, its black and white plumage making it an ideal subject to depict via this very striking medium:

Dr. Shuker, what a wonderful article on such an iconic species. I too wish that the Great Auk has survived in some remote northern isle and is waiting for conservationists & scientists to bring it back from the brink of extinction. Your blog is one of the gems of the internet!

ReplyDeleteHigh Regards,

Keith