Long before I’d even heard of Dr Bernard Heuvelmans, let alone read his seminal cryptozoological tome, On the Track of Unknown Animals, I’d already been greatly influenced by a very noteworthy, albeit entirely fictitious, figure of considerable relevance to mysterious and undiscovered beasts. I am referring of course to animal linguist genius Doctor Dolittle (or Dr John Dolittle MD, to give him his full title), created by Hugh Lofting. His fascinating adventures and discoveries featured in no less than 12 wonderful children’s novels by Lofting - all of which I had read and re-read many times with great joy during my formative pre-teen years.

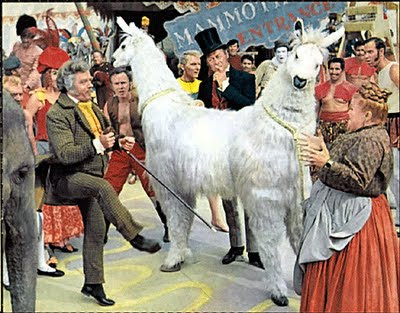

They also formed the basis for an equally delightful film musical, ‘Doctor Dolittle’, released by 20th Century Fox Studios in 1967. One of my all-time favourite films, it starred Rex Harrison in the eponymous role, alongside Anthony Newley, Samantha Eggar, Richard Attenborough, and a scene-stealing supporting cast of real-life animals. It featured a very tuneful selection of thoroughly charming songs too, composed by Leslie Bricusse (one of which, ‘Talk to the Animals’, went on to win an Academy Award for Best Song).

They also formed the basis for an equally delightful film musical, ‘Doctor Dolittle’, released by 20th Century Fox Studios in 1967. One of my all-time favourite films, it starred Rex Harrison in the eponymous role, alongside Anthony Newley, Samantha Eggar, Richard Attenborough, and a scene-stealing supporting cast of real-life animals. It featured a very tuneful selection of thoroughly charming songs too, composed by Leslie Bricusse (one of which, ‘Talk to the Animals’, went on to win an Academy Award for Best Song).

Showing the film musical's version of the pushmi-pullyu (Dr Karl Shuker)

During his varied escapades as chronicled by Lofting, the good Doctor encountered many different kinds of animal, ranging from the mundane to the marvellous - including a select few that were unquestionably unknown to modern-day science, and which so enthralled me that I can state in all honesty that the onset in my childhood of what would become a lifelong interest for me in cryptozoology was due in no small way to my fascination with these latter mystery beasts.

Consequently, it seemed only right that ShukerNature should survey some of Lofting’s most significant literary cryptids from the Doctor Dolittle series of novels, so here are six of my particular favourites.

THE PUSHMI-PULLYU

Consequently, it seemed only right that ShukerNature should survey some of Lofting’s most significant literary cryptids from the Doctor Dolittle series of novels, so here are six of my particular favourites.

THE PUSHMI-PULLYU

Out of all of the extraordinary creatures that appeared in Hugh Lofting’s series of Doctor Dolittle novels, it was the pushmi-pullyu that was unquestionably the most readily identifiable member of Dolittle’s marvellous menagerie, due not only to Lofting’s own input but also to this bicranial wonder’s very memorable appearance in the afore-mentioned Doctor Dolittle film musical from 1967.

Here is how Lofting introduced the pushmi-pullyu, native to darkest Africa and exceptionally elusive, in the very first Dolittle novel, The Story of Doctor Dolittle (1920):

"Pushmi-pullyus are now extinct. That means, there aren't any more. But long ago, when Doctor Dolittle was alive [early 1800s], there were some of them still left in the deepest jungles of Africa; and even then they were very, very scarce. They had no tail, but a head at each end, and sharp horns on each head. They were very shy and terribly hard to catch...[The native people] get most of their animals by sneaking up behind them while they are not looking. But you could not do this with the pushmi-pullyu because, no matter which way you came towards him, he was always facing you. And besides, only one half of him slept at a time. The other head was always awake and watching. This was why they were never caught and never seen in Zoos. Though many of the greatest huntsmen and the cleverest menagerie-keepers spent years of their lives searching through the jungles in all weathers for pushmi-pullyus, not a single one had ever been caught. Even then, years ago, he was the only animal in the world with two heads."

This is not entirely true, of course. There are many fully-confirmed cases of dicephalous or bicephalic (i.e. two-headed) animals on record, including various specimens of two-headed snakes, terrapins, lambs, calves, and even, rarely, humans. However, in every one of these cases, the two heads emerge either from a single neck or, if each head has its own neck, from a single upper torso. What made the pushmi-pullyu so very special is that its heads emerged from opposite ends of its body. Indeed, its body was actually two front halves fused together in opposite directions at their mid-riff.

Such an extraordinary entity is known technically as an amphicephalus, and in reality is exceedingly rare. Indeed, I know only of a few semi-amphicephalic terrapins, which were conjoined twins joined end to end, and, in contrast to the pushmi-pullyu, each twin had an almost fully-formed body, not just a front half.

A semi-amphicephalic terrapin (public domain)

The much more extreme condition exhibited by the pushmi-pullyu, conversely, would have rendered it an anatomical impossibility in real life – if only for the fundamental physiological reason that it would not have been able to defaecate, having no anus! Happily, such indelicate matters were discreetly passed over by Lofting, who wrote his novels in a more genteel age when, unlike in today’s brasher times, such subjects were most definitely off-limits in a children’s book (even though I would hazard a guess that, schoolboys being schoolboys whatever decade they happened to be born in, the pushmi-pullyu’s excretory paradox attracted its fair share of sniggers and risible comments even back in the 1920s!).

What an amphicephalic llama would look like

Moving swiftly on: just as intriguing as its anatomy was its taxonomy. Just what was the pushmi-pullyu? In the film musical, it was simply portrayed as an amphicephalic Tibetan llama (even though Tibet is normally home to lamas, not llamas!), but in the novel Lofting revealed that it had a much more complex, interesting ancestry:

"Excuse me, [said Doctor Dolittle] surely you are related to the Deer Family, are you not?"

"Yes," said the pushmi-pullyu "to the Abyssinian Gazelles and the Asiatic Chamois on my mother's side. My father's greatgrandfather was the last of the Unicorns."

"Excuse me, [said Doctor Dolittle] surely you are related to the Deer Family, are you not?"

"Yes," said the pushmi-pullyu "to the Abyssinian Gazelles and the Asiatic Chamois on my mother's side. My father's greatgrandfather was the last of the Unicorns."

Reading through the pushmi-pullyu’s description of its own ancestry, one might initially assume that the most cryptozoological aspect of it was this very curious creature’s derivation on its paternal side from the unicorn lineage. In reality, however, its maternal side was no less interesting either, because there is no such animal as the Asiatic chamois known to science. The only modern-day chamois, Rupicapra rupicapra, is almost entirely confined to Europe (it also exists a little way into Asian Turkey). So how can we explain Lofting’s assertion?

It may of course simply be that Lofting was mistaken, wrongly assuming that the chamois was Asian in zoogeographical distribution. Alternatively, he may have been loosely referring to one of the chamois’s close relatives - the serows, the gorals, the tahrs, or the takins, all of which, like the chamois, are known as goat-antelopes, but all of which, unlike the chamois, are Asian.

Chamois on Czechoslovakian postage stamp (public domain)

Back in the age when the Doctor Dolittle books were set (the early 1800s), anything – or anyone – with two heads invariably winded up on display in a sideshow or circus. And sure enough, so did the pushmi-pullyu, though in this instance it was a voluntary act, as it wanted to help the Doctor raise enough money to pay for a boat that he had borrowed but which had later been shipwrecked. The pushmi-pullyu’s arrival at the circus - whose astonished owner, the normally world-weary, seen-it-all showman Albert Blossom, was forced to concede in a boisterous song-and-dance number that “I’ve never seen anything like it!” (listen to it here) - provides one of the most entertaining scenes of all in the film musical, enhanced enormously by a glorious, deliberately over-the-top performance by none other than Richard Attenborough, the eminent actor brother of Britain’s foremost television naturalist, David Attenborough.

The pushmi-pullyu at Blossom's Circus in the 1967 20th Century Fox Studios film musical, 'Doctor Dolittle' ((c) 20th Century Fox - reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

How sad, therefore, that the pushmi-pullyu was not real – one could well imagine the whispered, reverential tones of Richard’s brother discussing its origins and behaviour in an episode of ‘Life On Earth’!

Join me again for Part 2 of this article (click here to access it), when I’ll be casting a glance over a couple of giant aquatic cryptids encountered by the good Doctor on his travels; and click here to access Part 3, when I'll be investigating two huge insects and a beautiful bird all known well to him but not known at all to the rest of science.

And here's one I made earlier - my very own pushmi-pullyu! ((c) Dr Karl Shuker)

Of course, neither chamois nor gazelles are of the "deer Family", both being bovids.

ReplyDeleteThe mythological unicorn has also been theorised to have been a bovid - either an ox with a single central horn instead of the usual pair due to either mutation or ancient surgical experimentation, or something like an oryx or gemsbok seen in profile with its 2 horns lined up and looking like one. I prefer the Giant Steppe Rhinoceros (Elasmotherium) theory tho...

Absolutely! Lofting seems to have had only a fairly tenuous grip on mammalian taxonomy, lol. Yes, in my book Dr Shuker's Casebook (2008), I've devoted a very extensive chapter to unicorns of many kinds, and have discussed a wide range of possible zoological identities and explanations, even including the Vu Quang ox (saola) as a possible contender for the Chinse unicorn or ki-lin, as well as a late-surviving Elasmotherium for certain Asian unicorn reports.

ReplyDeletei love llamas and camals

ReplyDeleteI've just learned that the logo of the annual palindromists awards, the Symmys, is an amphicephalic... mammal... of similar design to the pushmipulyu of the novels. Having just read the last 2 comments, I'm going to describe my grip on mammalian taxonomy as "fairly tenuous" ;) while simply reporting that the animal in question has long pointed horns swept back, and a slightly bulbous muzzle. If that makes sense. :) Or at least they did in the first year of the awards. I hope this image link works. If not, here's a RobWords video at a time where the image appears.

ReplyDelete