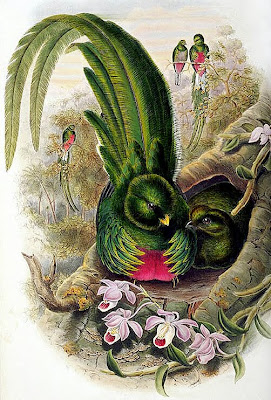

Resplendent quetzal - male in breeding plumage (painting by John Gould)

Resplendent quetzal - male in breeding plumage (painting by John Gould)El Escorial, also known as the Escurial, is a palatial architectural masterpiece of such splendour that its countless admirers refer to it as the 8th Wonder of the World. Commissioned by King Philip II, constructed from 1563 to 1584, and situated in Madrid, Spain, it houses the monastery of San Lorenzo (St Lawrence), a basilica, a library, the Royal Pantheon, the palaces of the Bourbons and Austrians, and a magnificent collection of fine art by such masters as Titian, Tintoretto, Velasquez, El Greco, Rubens, Dürer, and Bosch.

El Escorial also contains 515 reliquaries, containing no fewer than 7421 holy relics. One of these relics forms the subject of this article, because it is of particular cryptozoological interest - and for good reason. Constituting a single, but very singular, feather of extraordinary beauty, it lays claim to an even more extraordinary identity - for according to traditional belief, it originated from one of the wings of the archangel Gabriel.

A few centuries ago, this remarkable plume was a celebrated religious treasure, famous throughout Europe, but today its existence - if indeed it still exists - is largely unknown. Indeed, when I wrote in January 2001 to the monastery of San Lorenzo, housed within El Escorial, requesting information concerning the Gabriel feather, the monastery’s Keeper of National Heritage, Carmen Garcia-Frias Checa, wrote back denying all knowledge of it. Nevertheless, it definitely existed at one time. Perhaps its best-known observer was William T. Beckford (1759-1844), an exceedingly wealthy English author-traveller, who set forth on several extensive forays around Europe, visiting sites and buildings of religious significance in Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

During one such excursion, in 1787, Beckford journeyed to El Escorial, where he was privileged to see Gabriel's feather, and he subsequently documented it in one of his travelogues, Italy, With Sketches of Spain and Portugal, vol. 2 (1834). The publication of this work is of especial note, because it followed closely upon the formal description of a truly exceptional new species of bird that initially influenced scientific speculation concerning possible ornithological origins for the Gabriel feather.

El Escorial also contains 515 reliquaries, containing no fewer than 7421 holy relics. One of these relics forms the subject of this article, because it is of particular cryptozoological interest - and for good reason. Constituting a single, but very singular, feather of extraordinary beauty, it lays claim to an even more extraordinary identity - for according to traditional belief, it originated from one of the wings of the archangel Gabriel.

A few centuries ago, this remarkable plume was a celebrated religious treasure, famous throughout Europe, but today its existence - if indeed it still exists - is largely unknown. Indeed, when I wrote in January 2001 to the monastery of San Lorenzo, housed within El Escorial, requesting information concerning the Gabriel feather, the monastery’s Keeper of National Heritage, Carmen Garcia-Frias Checa, wrote back denying all knowledge of it. Nevertheless, it definitely existed at one time. Perhaps its best-known observer was William T. Beckford (1759-1844), an exceedingly wealthy English author-traveller, who set forth on several extensive forays around Europe, visiting sites and buildings of religious significance in Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

During one such excursion, in 1787, Beckford journeyed to El Escorial, where he was privileged to see Gabriel's feather, and he subsequently documented it in one of his travelogues, Italy, With Sketches of Spain and Portugal, vol. 2 (1834). The publication of this work is of especial note, because it followed closely upon the formal description of a truly exceptional new species of bird that initially influenced scientific speculation concerning possible ornithological origins for the Gabriel feather.

The archangel Gabriel (artist unknown, Byzantine painting, late 1300s)

The quetzal is indisputably one of the world’s most beautiful species of bird. It is native to Central America, including Mexico and Guatemala, where it was deemed sacred by the Toltecs, Mayans, and Aztecs. Indeed, it is the national symbol of Guatemala even today, and this country’s unit of currency is named after it too. Moreover, if a person stands in front of the mighty 1100-year-old Mayan pyramid of Kukulkan (El Castillo) at Chichén Itzá near Cancún, Mexico, at the base of its staircase, and claps their hands, the pyramid will emit a distinctive chirping echo - but not just any chirp. In 2002, Californian acoustical engineer David Lubman and a team of Mexican researchers revealed that it constituted a precise phonic replica of the quetzal’s call (National Geographic Today, 6 December)! Some researchers, such as Ghent University mechanical construction specialist Dr Nico F. Declercq, have since questioned whether this acoustical anomaly was intentional on the part of the pyramid’s Mayan designers and architects (Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, December 2004), but if not it is surely a formidable coincidence.

Belonging to an exclusively tropical taxonomic order of brightly-plumaged species known as trogons, and sporting a shimmering emerald-green plumage complemented by scarlet underparts, the quetzal is instantly distinguished from all other birds during the breeding season. This is when the male, whose body measures a mere 18 in, grows a quartet of extremely elongate tail plumes, 2-3 ft in length. These undulate as it flies, affording it the appearance of a feathery snake, and inspiring the Aztecs to associate it with their sky god Quetzalcoatl, often portrayed as a green plumed serpent.

Yet despite its flamboyant plumage, the quetzal's debut within the ornithological literature of the Western world was unexpectedly belated, and controversial too. In 1831, after receiving a description of the quetzal from Duke Paul of Würtemberg, the eminent French zoologist Baron Georges Cuvier stated that in his opinion this bird's astonishing tail plumes could not be genuine. Instead, they must have been created artificially, i.e. they were composite feathers, composed of several individual plumes artfully combined together. Interestingly, a skilfully-constructed composite feather is one identity that had already been aired by some naturalists as an explanation for the celebrated feather of Gabriel.

However, ornithologist Dr Pablo de la Llave was well aware of the quetzal's authenticity, because he had first become acquainted with this spectacular species prior to 1810, from examining over a dozen specimens obtained by natural history expeditions in Central America and maintained in the palace of the Retiro near Madrid. Accordingly, in 1832 he formally christened it Pharomachrus mocinno in the Registro Trimestre (a Mexican journal), honouring Mexican naturalist Dr J.M. Mociño.

Once the quetzal became known in scientific circles, it was inevitable that this species (now known specifically as the resplendent quetzal, thereby distinguishing it from five other, less spectacular quetzal species that lack the long tail feathers of breeding male P. mocinno) would be mooted as a possible explanation for the Gabriel feather. Certainly the breeding male quetzal's tail plumes are exquisite enough to have inspired speculation, perhaps, by non-zoological theologians as to whether they might conceivably be of divine rather than merely mortal origin.

Moreover, in view of this species' eyecatching appearance, it is also possible that during the 1500s the Spanish conquistadors brought some preserved quetzal skins or plumes back home with them when they returned to Spain after conquering Mexico (which in those days incorporated Guatemala too). Needless to say, if one of these should thence have found its way into the collections of the newly-built Escorial, then surely we would not need to look any further for an explanation of the Gabriel feather – or would we?

Unfortunately, this elegant solution has a fatal flaw, as ornithologists reading Beckford's travelogue, published two years after Llave's description of the quetzal, would soon discover. For in his account of the Gabriel feather, Beckford revealed that it was not green, but was in fact rose-coloured. Exit the quetzal from further consideration!

Yet if not a quetzal plume, from which bird could the Gabriel feather have originated? (Worth noting here, incidentally, is that the concept of angels possessing feathered wings is a relatively recent one, nurtured largely by Renaissance artists and hence dating back only a few centuries, with no foundation in early theological lore.)

'Rose-coloured' conjures up images of flamingos, but it is difficult to believe that feathers from species so familiar to European ornithologists as these leggy waterbirds could be lauded as holy, sacred plumes derived from the wings of archangels. In my opinion, there is a much more convincing identity for the Gabriel feather - and one which, if not truly divine, does at least sound heavenly.

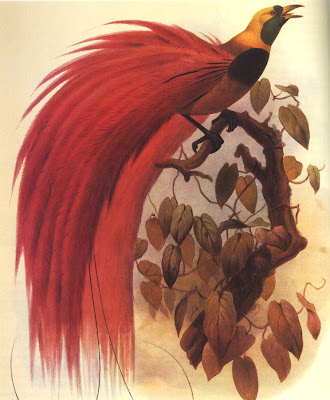

New Guinea's extravagantly-plumaged birds of paradise first came to European notice in 1522, when the survivors of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan's once-mighty fleet returned home to Europe, docking in Seville, Spain. On board were many feathery skins from these beautiful birds, bought from New Guinea tribesmen, but preserved minus their feet - so that for more than three centuries, scientists erroneously assumed that these avian wonders really were footless, spending their entire lives in unending flight amid the sky's cloud-dappled realms.

In reality, during the breeding season the males of some species possess gaudy bunches of long gauzy plumes that cascade in eyecatching fountains of colour from beneath their wings and tail. Males of Count Raggi’s bird of paradise Paradisea raggiana in particular are sumptuously adorned with vivid sprays of bright red or rose-coloured plumes - thus corresponding closely with the appearance of the Gabriel feather. Could it be, therefore, that this is the true identity of the Escorial's enigmatic plume - a lone feather derived from a male P. raggiana skin brought back from New Guinea to Spain by Magellan's fleet a mere four decades before work began upon the Escorial's construction?

How very appropriate it would be if a feather once thought to be from an archangel of Heaven ultimately proved to be from a bird of paradise.

NB - For the most comprehensive investigation ever published concerning this and other supposed archangel feathers, see my book Karl Shuker’s Alien Zoo (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2010).

Count Raggi's bird of paradise - male in breeding plumage

Could we be dealing with a macaw tail feather? Those are certainly long and spectacular and they can be red.

ReplyDeleteThe Gabriel feather was said to be very long, around the same length as a male quetzal plume, i.e. longer than macaw tail feathers. Moreover, on account of the prevalence of macaws in Europe anyway, brought back by travellers to the New World and frequently depicted in paintings (see various other ShukerNature blog posts of mine for some such examples), I think that a macaw feather would have been readily identified as such, whereas something more exotic, like a bird of paradise plume, might not have been so easily recognised for what it was.

ReplyDeleteThe Quetzal is magnificent. Living in cloud forests of Central America it is hard to find. I feel that it should not be caught for its tail feathers. It would be wonderful to have these birds here where I live. A bird sanctuary with exotic birds such as the Quetzal and Manakins Cotingas Todies and Trogons in an outdoor setting with acres of land to fly in would be like heaven to me. The birds should be tamed so visitors can get a good close look and maybe even feed them by hand. I love exotic tropical songbirds.

ReplyDelete