The

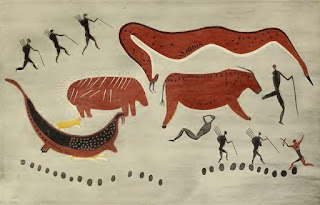

baffling Bushman rock painting at Brackfontein Ridge, in South Africa's Orange

Free State, that depicts an unexpectedly walrus-like mystery beast (public

domain)

Adam Thorn from Perth in Western

Australia is a famous animal adventurer, jungle explorer, and co-host of the

History Channel's very popular 'Kings of Pain' show. He is also a longstanding

Facebook friend of mine, and shares my interest in mysterious, unidentified

creatures, especially an extremely curious African cryptid referred to

colloquially as the jungle walrus but which is little known even in

cryptozoological circles, let alone beyond them, yet is ostensibly represented

by a fascinating if perplexing Bushman rock painting (petroglyph).

Consequently, please allow me to present for the first time here on

ShukerNature a comprehensive survey of this and other tusk-touting aquatic anomalies

that have been reported down through the ages from several different regions of

sub-Saharan Africa, and which also feature in my newest book (#32), to be

published later this year. Hoping that you enjoy it, Adam – and everyone else

too!

Many

years ago, a pygmy from the Democratic Republic of the Congo's Ituri Forest

(where Sir Harry Johnston famously discovered the okapi in 1901) identified a

picture of a walrus shown to him by aptly-named big-game hunter John A. Hunter

as a savage, nocturnal beast that lived in the deepest parts of the forest. Not

surprisingly, Hunter dismissed this claim of a 'jungle walrus' as nothing more

than the pygmy's desire to please him, as he noted in his book Hunter (1952).

As

will be seen here, however, it may be prudent not to dismiss entirely the

pygmy's claim, because a startling number of such creatures, all sharing a

fundamental similarity of form, lifestyle, and habitat, are documented within

the chronicles of cryptozoology – not least of which is a certain highly

enigmatic rock painting discovered at Brackfontein Ridge in South Africa's

Orange Free State. How old this native Bushman artwork is, whether it dates

back a mere couple of centuries or is possibly significantly older, remains

debatable, but even more so is what it depicts.

George William Stow (public domain)

It

first attracted attention in 1930, when it was depicted in Rock-Paintings in

South Africa, a sumptuous work by

George William Stow and Dorothea F. Bleek. The text of this book was written by

anthropologist Bleek to accompany its numerous full-page illustrations that

consisted of meticulous, often full-colour copies of South African petroglyphs

that had been prepared between 1867 and 1882 by Stow (1822-1882), an

English-born trader, historian, and geologist, who had been passionately

interested in South African native races, especially the Bushmen. His travels

as a trader had taken him to many little-visited South African localities

containing petroglyphs, and his interest in them had led him to prepare his

copies – which proved very valuable, because some of the originals no longer

exist, have subsequently become damaged or worn, or are in quite inaccessible

sites.

According

to Bleek, the location of the particular petroglyph under consideration here in

this ShukerNature article was a cave in Brackfontein Ridge, situated on an Orange

Free State farm named La Belle France that was owned back then by a Mr Connor

Swanepool, and its subject was one of several strange animals portrayed together there. As now seen, this remarkable petroglyph

portrays an animal that bears a startling resemblance to a walrus - from its

rounded head displaying two very large downward-curving tusks to its elongated,

tapering body and paddle-like limbs. Indeed, its only prominent difference from

the latter pinniped is that it possesses a long tail, whereas during 23 million

years of evolution from original terrestrial ancestors the walrus has lost its

tail (but see later for a putative explanation of this morphological

distinction). No satisfactory mainstream zoological identification of this petroglyph-portrayed

walrus lookalike has been proffered so far, nor of the other equally odd

animals depicted alongside it – Bleek deemed them to be mythical beasts - but

several very comparable cryptozoological counterparts have been reported across

tropical Africa, and all of them are claimed in eyewitness testimonies to be

predominantly aquatic.

Stow's copy of the collection of petroglyphs at Brackfontein that

includes the jungle walrus (public domain)

The

marked predominance of this feature is acknowledged in the various native names

given to these 'jungle walruses' by different native peoples. In the Central

African Republic (CAR), for instance, the Banda speak of the mourou n'gou or

muru-ngu (meaning 'water leopard'); the Baya speak of the dilali ('water

lion'); the Sangho of the ze-ti-ngu or nze ti gou ('water panther'); and the

Zande of the mamaimé ('water lion') or (just to be different) ngoroli ('water

elephant'). Judging from all but the last-mentioned term, these creatures are

quite clearly feline, an assumption supported by the various descriptions of

them on record.

According

to an old Banda tribesman called Moussa, interviewed in 1934 by Lucien Blancou

(formerly Chief Game Inspector in what was then French Equatorial Africa -

subsequently split into Chad, the CAR, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon),

the mourou n'gou was somewhat larger than a lion in size (Moussa estimating its

length at about 12 ft), with an overall body shape and pelage background colour

reminiscent of a leopard's, but additionally adorned with stripes. Curiously,

its paw-print was described as "containing a circle in the middle".

Apparently,

Moussa at some stage had observed one of these creatures emerging from the

Koukourou river in close proximity to a soldier in a canoe. The mourou n'gou

seized the hapless man and dragged him down into the water. As a result of this

incident, the detachment to which the beast's victim had belonged decided not

to cross the river at this point thereafter but instead at a new location some

considerable distance to the east In 1945, a native gunbearer called Mitikata

drew a sketch of the mourou n'gou, which showed a small-headed, large-fanged

creature about 8 ft long, with a plump, uniformly brown-coloured body and a

panther-like tail.

Intriguingly,

the Banda also use the name 'mourou ngou' to signify a very different, known

species – central Africa's giant otter shrew Potamogale velox. Its English name derives from its deceptively

otter-like outward appearance and its former classification as a relative of

shrews within the taxonomic order Insectivora (but more recently it has been

reclassified as a member of the exclusively African taxonomic order

Afrosoricida, alongside tenrecs and golden moles). Like real otters, it lives

an aquatic, piscivorous existence, but has a head-and-body length of only about

1 ft plus a slightly shorter tail, yielding a total size that is not only much

smaller than that of real otters but also very much smaller than estimates for

the mourou ngou. Nor does its uniformly unpatterned, brown fur dorsally and

paler ventrally resemble in any way the prominently striped or spotted coat of

the latter cryptid, whereas any suggestion of large fangs is conspicuous only

by its absence in relation to the giant otter shrew. Clearly, therefore,

whatever the cryptozoological mourou ngou may be if it truly exists, it is

certainly not the giant otter shrew.

Painting of giant otter shrew, from the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of

London, 1869 (public domain)

During

December 1994-January 1995, Belgian cryptozoologist Eric Joye led a two-man

expedition, dubbed 'Operation Mourou N'gou', in search of this elusive

creature. Although they failed to spy it themselves, Joye and his team-mate,

hunting guide Willy Blomme, succeeded in gathering some very interesting

anecdotal evidence - probably the most extensive obtained since the material

collected here during the 1930s by Lucien Blancou (Cryptozoologia, September 1994, September 1996).

Claiming

to have narrowly avoided being propelled into the Bamingui River by such an

animal as he sat fishing at the river's edge one afternoon in February 1985, a

native guide called Marcel told Joye that the mourou n'gou hunts in pairs - one

waiting in the river to seize any prey chased into the water by the other. According

to Marcel, the mourou n'gou compares with a leopard in shape and size, and its

pelage is ochre, dappled with blue and white spots that are very distinct upon

its back but less well-defined upon its flanks. It has a long tail, hairier

than the leopard's, and its head is said to be a little like that of a civet

(does this mean that, like a civet, it has a dark face mask?), but its teeth

are very large and resemble those of a Big Cat such as the leopard or lion. Marcel

followed the mourou n'gou's trail, which was like a leopard's but bigger. Also,

when it runs, it leaves behind the impression of claws, which is not usual for

a leopard.

A

second so-called water leopard is the nzemendim, spoken of by the natives in

the N'velle distinct of Yaounde, Cameroon, and documented in Gorillas Were

My Neighbours (1956), written by Fred G. Merfield and Harry Miller. The

locals claimed that it was a type of leopard that lived in small rivers, and

frequently carried off women and children. After several failed attempts to

spot this dangerous mystery beast, one of this book's authors believes that he

finally achieved success:

One morning, just as it was getting light, an

animal swam rapidly upstream and landed on the opposite bank. The light was

still poor, and all I could see was something furry, spotted and four-legged,

so I fired. The animal spun round and dived back into the water. I thought it

was lost, but when the sun rose and my men turned up, we found it dead and

washed ashore a few hundred yards downstream. It was a big dog-otter, a very

old fellow whose fur had gone grey and blotchy, giving the appearance of spots.

The natives would not admit that this was their nzemendim, and having no more

time to spare I gave up and went home.

Could some 'jungle walruses' be extra-large

specimens of otter? Standing alongside a statue of a giant otter in South

Africa's Kirstenbosch Gardens (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Lucien

Blancou learnt a little concerning another type of supposed aquatic mystery

cat, the dilali. According to an interpreter at Bozoum in eastern Ubangi-Shari

(a French colony that was part of what was then French Equatorial Africa), it

possessed the body of a horse and the claws of a lion, as well as large

walrus-like tusks (this last-noted feature was mentioned to Blancou by a Zande

native guard).

Then

there is the nze ti gou, a nocturnal beast of leopard stature, having red fur

marked with pale stripes or spots, living within hollows in large rivers, and

emitting a thunderous noise. Such creatures are not restricted to the CAR and

Cameroon either.

The

Mbunda tribe of eastern Angola speak of the coje ya menia ('water lion'), which

attracted the interest of Ilse von Nolde during her sojourn there in the early

1930s, and which she subsequently wrote about in an article published by the

periodical Deutsche Kolonialzeitung

in 1939. Like the nze ti gou, this beast is well known to the natives for its

loud rumbling vocals, and, although principally aquatic, sometimes ventures

forth onto dry land. Like the other beasts mentioned here, it too is armed with

large canine teeth or tusks, and supposedly kills hippopotamuses with them,

despite its own smaller body size. The observations and dealings of von Nolde

with this region's natives convinced her that the coje ya menia was not based

upon misidentified sightings of crocodiles or hippos, or of these species'

spoor. On the contrary, the natives were very adept at identifying and

interpreting spoor.

Reconstruction of coje ya menia attacking

hippopotamus, by Wilhelm Eigener (public domain)

She

was equally convinced of the sincerity of a Portuguese lorry driver who told

her that in the company of some natives, he had actually tracked a coje ya

menia that had chased after and killed a hippopotamus. Sure enough, the tracks

of the two beasts had led to the mutilated carcase of a hippo - yet no part of

it had been eaten. The tracks of the coje ya menia were smaller than those of

the hippo, and although somewhat reminiscent of an elephant's in shape, they

additionally contained the impression of toes. Worth noting here is that as far

back as 1947 in a Kosmos article,

renowned German cryptozoologist Dr Ingo Krumbiegel had suggested a surviving

sabre-tooth as a possible identity for this Löwe des Wassers ('water lion').

Also

worth keeping in mind is a certain Ngona Horn folktale of the Wahungwe people

from Zimbabwe, documented in African

Genesis (1983) by Prof. Leo Frobenius and Douglas Fox. For it refers to

some very odd felids - "lions under the water", and is itself

entitled 'The Water Lions'. Could these be comparable with nearby Angola's coje

ya menia?

The

Zande or Azande is a native African tribe indigenous to the northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the

Congo (DRC), the Republic of South Sudan, and the southeastern section of the

CAR – which in combination is often referred to as Zandeland. The Zande people

speak of several mysterious beasts that may possibly be cryptozoological in

nature. One of the most intriguing of these is the mamaimé or water leopard –

but one that sounds very different from both of the previous two versions. In

an article published by the journal Man in September 1963, Oxford

anthropologist Prof. E.E. Evans-Pritchard noted that the Zande's water leopard

had been described to him by them as follows:

The water leopard is a

powerful kind of beast, dark and with a blackish skin and a head of hair shaggy

to the neck. Its pads are very large and its palms hairless like those of a

man. It has powerful teeth in its mouth. It seizes a person as does a

crocodile. It appears in places of deep water. Its eyes are very large and red,

like the seeds of the nzua vegetable [like tomatoes]. It lives in holes

as crocodiles do, but where it resides there is water and many fish near it.

This water never dries up, for it is its home.

Prof.

Evans-Pritchard was also told that this strange creature has hair like a man's

that falls over its body, and he noted that a Major P.M. Larken had stated in

an article published in 1926 that water leopards are said to live in deep pools

within large rivers, and that big fissures in the banks of rivers have often

been pointed out by locals as being these aquatic cryptids' homes.

Evans-Pritchard doubted that the water leopard genuinely existed but was at a

loss as to how to explain reports of it.

Moving

to the DRC's southern regions, we encounter reports of yet another similar

animal, known variously as the simba ya mai, ntambue ya mai, and ntambo wa luy,

all of which translate as 'water lion'. Further mystery beasts apparently

belonging to this same type include the Kenyan ol-maima and the Sudanese

nyo-kodoing.

Could aquatic sabre-tooths exist in remote regions

of tropical Africa? (© Randy Merrill)

From

description and native nomenclature a feline identity seems probable, and from

their formidable upper canines an undiscovered modern-day species of

sabre-tooth (machairodontid) has been popularly proposed by some

cryptozoologists (see below), although the fossil record attests that all

African sabre-tooths had vanished before the Pleistocene's close, around 11,000

years ago). Moreover, the existence of an aquatic sabre-tooth is a very bizarre

concept. Certainly there is no evidence from fossil finds to suggest that any

extinct machairodontid ever became adapted for this particular lifestyle. So is

it really possible that such a creature is the explanation for any or all of

the various mystery beasts described here?

Following

on from Krumbiegel's earlier suggestion, in his books Les Derniers Dragons d'Afrique (1978) and Les Félins Encore

Inconnus d'Afrique (2007) veteran

French cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans asserted that it was not only

possible but was, to his mind, more than likely. The principal arguments that

he put forward in support of this can be summarised as follows:

1)

Despite popular belief, many cat species are not afraid of water.

2) The

very effective utilisation by walruses of their own huge upper canines for

anchorage, dragging themselves on to land or ice floes, and ploughing up the

sea bed sediment in search of modest-sized prey demonstrates that the

sabre-tooth's enlarged canines would be of great benefit for an aquatic

existence.

3)

Conversely, on land such teeth would surely have been a great handicap to the

sabre-tooth when attempting to tear off and devour pieces of meat from its

prey.

4) Due

to this, sabre-tooths would have faired badly in competition with true felids

of comparable size, e.g. lions and leopards, and ultimately may have been

forced to move into ecological niches unoccupied by such cats - namely remote

mountains and aquatic realms (which just so happen to be the very environments

from which reports of alleged modern-day sabre-tooths are emerging – a future

ShukerNature article will explore tales of terrestrial, montane sabre-tooth

lookalikes).

Les Félins Encore Inconnus d'Afrique

(© L'Oeil du Sphinx – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use

basis for educational and review purposes only)

Consequently,

Heuvelmans believed that sabre-tooths could exist very readily in an aquatic

environment simply by paralleling the walrus's lifestyle. Moreover, if

challenged by potential rivals such as elephants or hippos, the sabre-tooth

would be more than amply equipped to dispose of them, and could even drink the

blood spurting from any vanquished opponent's neck (some authorities believe

that the fossil terrestrial sabre-tooths were themselves sanguinivorous). Its

carcase could serve as a food source too. For if dragged underwater by the

sabre-tooth and allowed to decompose, the carcase's meat would eventually

soften, enabling it to be torn off in pieces and devoured more readily by the

sabre-tooth, thereby cancelling out the problems that the felid might otherwise

experience due to its cumbersome canines.

Once

again, this suggestion is supported by walrus activity. Some walruses have been

reported killing seals and small whales, and lumps of blubber and seal remains

(soft and/or from decomposing beached carcases - hence easy to tear) have been

found in the stomach of some walruses.

Nor

have we come to the end of walrus parallels. Any sabre-tooth modified via

evolution for an aquatic existence that compared closely with that of a walrus

behaviourally would very likely follow a similar course morphologically too

(convergent evolution). Conversely, as

the known fossil sabre-tooths of Africa's early Pleistocene (2 million years

ago) displayed terrestrial-related morphology, any amphibious development must

have occurred since then. Yet it is rather unlikely that as drastic a change as

the complete loss of a tail via evolution would have occurred in so short

(geologically-speaking) a space of time (as noted earlier, it took 23 million

years for today's walruses, lacking a tail, to evolve from their original

terrestrial ancestors). Consequently, the Brackfontein Ridge rock painting is

precisely what we would expect a recently-evolved amphibious sabre-tooth to

look like - a more streamlined version of its terrestrial counterpart with

limbs modified for an aquatic life but with the tail not yet lost. Also worth

noting is that such a sabre-tooth may be expected to be larger than land-living

species, because the accompanying weight increase would be buoyed by its

surrounding liquid environment. This would explain the notable size of some of

the mystery beasts reported in this article.

Delightful 19th-Century walrus

engraving – this is one of the very first engravings that I ever purchased,

more than 30 years ago, and it has remained one of my favourites ever since, yet it has never

appeared in any of my writings, until now! (public domain)

Finally,

and in the time-honoured tradition of keeping the best (or at least the most

bemusing!) to the end, here is what must assuredly be the strangest jungle

walrus of all – the Kenyan dingonek. An aquatic beast of generally feline

appearance, familiar to the Wa-Ndorobo tribe, and allegedly once shot at by adventurer

John Alfred Jordan during the early 20th Century, Kenya's highly

elusive but exceedingly daunting dingonek is in the opinion of Heuvelmans another

possible member of the aquatic sabre-tooth association. Its fangs are huge; its

body is long and as wide as a hippopotamus's; its tail is lengthy and broad,

and swings gently against the river current when the animal is in the water; it

has four short legs, and its feet are as big as a hippo's, but they bear large

claws like those of a crocodile.

True,

it possesses one feature that initially seems to exclude it from a felid

identity – namely, a body covered in scales. Heuvelmans, however, considered it

more likely that these are merely optical illusions produced by light shining

upon a particularly reflective pelage, and one that also bears tufts of hair

that have adhered together as a result of the animal having been submerged in

water, thereby creating the effect of scales. Having said that, in his

description of an alleged first-hand encounter with a dingonek in 1905,

documented in his book Elephants and

Ivory: True Tales of Hunting and Adventure (1956), Jordan seemed very

emphatic that this creature was genuinely scaled:

I slid down the bank and got in the cover of the

bushes. There it was.

It was in midstream, about thirty feet from me, a

beast-fish, a creature from your nightmares. It was fifteen to eighteen feet in

length, with a massive head, not a head like a crocodile's, but flat-skulled

and round. It had two yellow fangs dropping from its upper jaw, and its back

was as broad as a hippo's, but it was scaled in beautifully overlapping plates,

as smooth and as intricate as those I've seen on an old Arabian cuirass. The

sunlight fell on those wet scales and was dappled by the leaves, and made them

seem as brilliantly colored as a leopard's coat. It had something of every

animal in it. It was impossible.

There was a broad tail, and this was swinging

gently against the current, keeping it midstream, keeping it stationary,

whatever it was.

At last I took aim on it...I aimed the .303 at the

base of the neck and gave it one solid round.

I saw the bullet hit, and heard it hit the way you

do at short range. The beast turned in a great flurry of yellow water until it

was facing the bank and my cover. It leaped into the air until it was standing,

or so it seemed, its pale belly scales vivid, ten or twelve feet on end.

[Jordan and his native helpers then fled through

the forest for 300 yards before halting, but after a time they cautiously

returned to the river] It had gone, but its spoor was all over the soft mud,

huge prints about the size of a hippo's, but clawed.

Some Wanderobo told me that they knew about this

thing, they called it a dingonek. The Kavirondo knew of it too. They had

seen more than one of them and made a god out of it whom they called

"Luquata." They were worried when they heard that a white man had

shot at Lukuata. They said that now they would all die of sleeping sickness,

and it is true that there was an epidemic of it among the Kavirondo that year.

Jordan's

noting that it was considered bad luck to kill a dingonek echoes a belief that

is also prevalent concerning DR Congo's equivalent mystery beast, the ntambo wa

luy or simba ya mai, as recorded in Charles Mahauden's book Kisongokimo

(1965). Such taboos have undoubtedly assisted in saving these potentially

dangerous creatures from extirpation.

Dingonek illustration based upon Jordan's

encounter, Wide World Magazine, 1917

(public domain)

At

much the same time as Jordan's sighting, another hunter spied a dingonek

floating on a log down the Mara River (also running into Lake Victoria) while

in high flood - but it quickly slid off and into the water. Near Kenya's Amala

River, the Masai call it the ol-maima and sometimes see it lying in the sun on

the sand by the riverside - but if disturbed, it slips into the water at once,

submerging until only its head remains above the surface.

Jordan

also documented his dingonek encounter in his later book, The Elephant Stone (1959), and here he emphasised its fangs and

scales:

Fifteen to eighteen feet long, with a massive head

shaped like that of an otter, two large fangs, as thick as walrus teeth,

descending from the upper jaw; its back as wide as a male hippo's, yet scaled

distinctly, like an armadillo; and I could see also why my Lumbwa [native

helpers] had spoken of a leopard's body, for the light reflected on the scales

in that cat's colours. Idly it switched a broad tail...

In a

much earlier account of his dingonek sighting, moreover, given by him to a

London Daily Mail newspaper reporter

almost 40 years before his own books were published, Jordan specifically stated

that this creature's two fangs "were like those of a walrus protruding

from its mouth" and that its body "was shaped like a hippopotamus but

scaled". However, after stating that he fired at it, Jordan then claimed:

"My further observations were cut short by the animal charging us",

and went on to say that he returned to the area the next day (Daily Mail, 16 December 1919). (Earlier

still is a 1917 article by him that appeared in Wide World Magazine.) Needless to say, these claims directly

contradicted Jordan's accounts in his two books, in which no mention was made

of the dingonek charging him, and in which he and his helpers returned not long

afterwards rather than the next day. Such notable discrepancies cannot help but

make me wonder just how reliable the remainder of his dingonek testimony was...

Dramatic dingonek representation that includes a

brow-borne horn and sting-tipped tail, features not normally ascribed to this

cryptid (© Randy Merrill)

Notwithstanding

this, the concept of aquatic felids is evidently not an alien one to native

Africans. And the close correspondence in such creatures' descriptions over so

far-reaching an expanse of Africa, cutting across many different tribal

cultures and histories too, is surely indicative that there is something more

substantial and fundamental to their accounts than mere folktale and

superstition. Time and reason enough, therefore, for the launching of a new

expedition by some enterprising seeker of mystery beasts to discover the

dingonek, meet the mourou n'gou, or even journey to the jungle walrus that may

– or may not – lurk in clandestine seclusion within the dark, shadow-enshrouded

heart of the Ituri Forest?

Last

but by no means least: an exactly comparable situation exists in South America

too, from where reports of mystery cats resembling terrestrial

mountain-dwelling sabre-tooths have emerged, as well as reports of

water-dwelling cryptids likened to aquatic sabre-tooths, and sometimes even to walrus-toothed

otters, such as Guyana's mystifying but deadly maipolina - but these must wait

for a future ShukerNature article…

This ShukerNature blog article is adapted

from my forthcoming 32nd book – more details to be posted here in

due course...

Artistic representation of the South American maipolina

(© Markus Bühler)

You've absolutely been on a roll recently, Karl, with a new article being published almost daily! I guess people need something to do during the Coronavirus lockdown.

ReplyDeleteThis one was informative reading, introduced me to a ton of African cryptids that I have never heard of until now. Neither did I know that there have been this much speculation into survival of sabretooth cats, for that matter, those stories were to my knowledge rare even in "alien big cat" cryptozoology.

Yes indeed, and there are also all of the terrestrial sabre-tooth reports on file from both tropical Africa and South America, plus the aquatic sabre-tooth reports from South America, all of which still require documentation by me here on ShukerNature, but I have done so in my two books on mystery cats.

DeleteI am always puzzled by claims such as that the sabre-tooth would have been severely handicapped by its long fangs. Features which are a handicap to survival would not be selected for and so could not evolve. But the sabre-tooth attribute has evolved more than once. We don't know what advantage the it conferred but it certainly did not condemn them to starvation.

ReplyDeleteI was writing those comments basically in the context of what Heuvelmans had speculated in his writings on this subject rather than expressing my own personal view, though his notions on how aquatic sabre-tooths might utilise their tusks in similar ways for similar purposes to what walruses do are valid. I agree that there must be some advantage to possessing sabre-like canines in view of how they have evolved more than once but those cats that possessed them were evidently less successful than those that didn't, otherwise they would be very much in visible existence today, whereas, if they do indeed still exist, are confined to much less visible localities.

DeleteThe depiction of the tusked animal looks a great deal like Bruce Champagne's class 2A sea serpent, with the long, thin tapering tail the long thin tusks, and scales. Perhaps as the animals mature, they move out to sea

ReplyDeleteTantalising! Anything related to sabretooth cats fascinates me, but I did not expect parallels between them and walruses. ;) It makes perfect sense when explained, too.

ReplyDeleteLooking at that snake like petroglyph with the horns does remind me of the Dingonek.

ReplyDeleteHow do the reports compare with the Giant River Otter, especially in South America?

ReplyDeleteIncreíble, Karl quiero hacer una expedición, necesito un permiso científico?

ReplyDeleteIn my opinion, the dingonek is probably a living gorgonopsid. These were mammal-like reptiles that had saber teeth and lived during the Permian period

ReplyDeleteMore likely an Enhydriodon than a Gorgonopsid.

ReplyDelete