A flying gurnard, depicted in Marcus

Bloch's 12-vol Encyclopedia of Fishes, 1782-95; note its toad-like profile

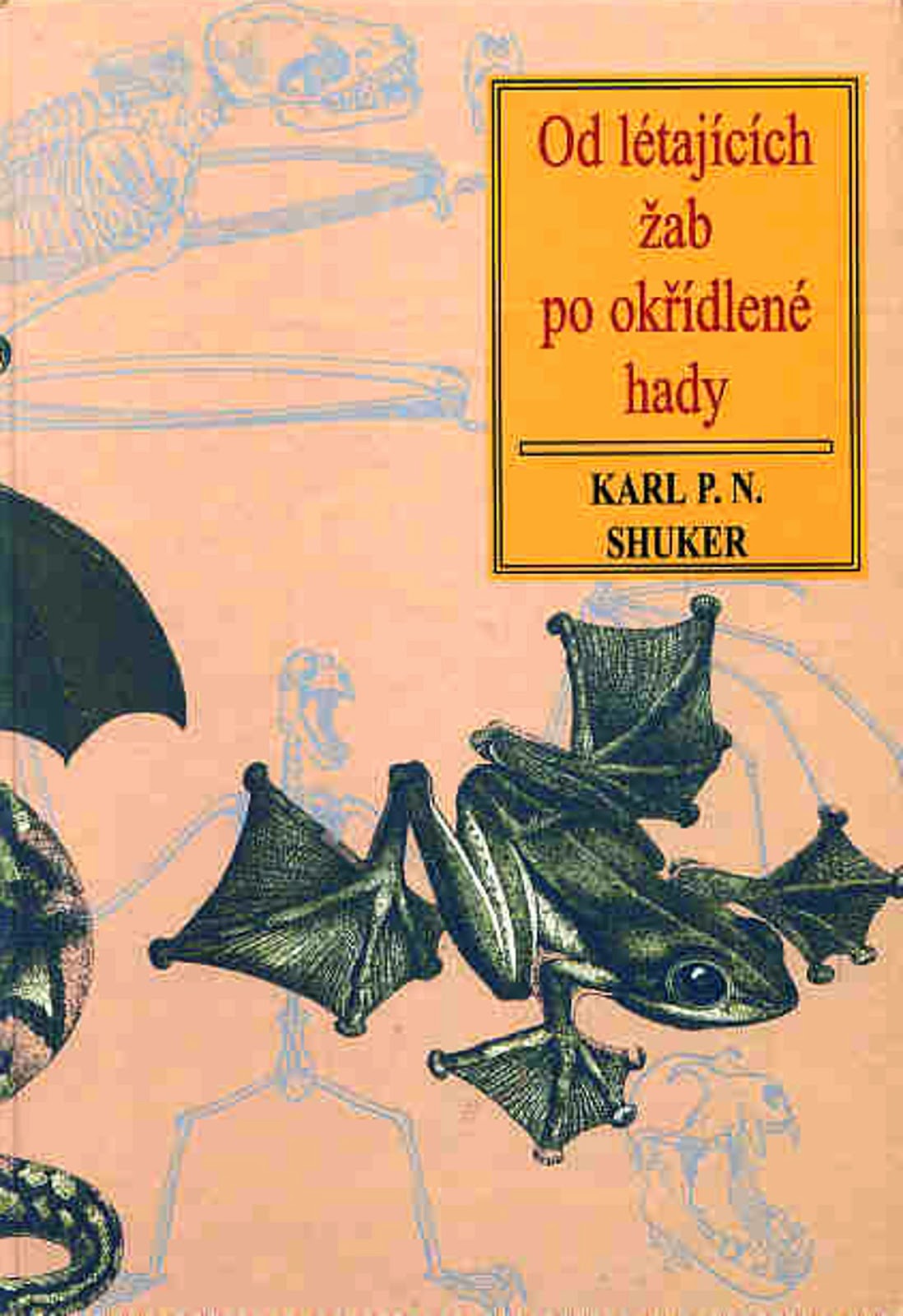

In my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (1997), the flying toad in

question that I chronicled was the llamhigyn y dwr or Welsh water leaper. At

that time, it was popularly assumed to be an obscure yet bona fide legendary

creature from traditional Welsh folklore. However, I subsequently learnt that

it was almost certainly a modern-day hoax invented during the early 1800s by an

inveterate, infamous spinner of yarns and other tall tales called Han Owen, as

exposed by CFZ researcher and native Welshman Oll Lewis.

My Flying Toads book alongside

my very own flying toad! (© Dr Karl Shuker)

In later years, conversely, as documented and

assessed within an entire chapter devoted to them in my newly-published book The Menagerie of Marvels: A Third Compendium of Extraordinary Animals (CFZ Press: Bideford, 2014), I uncovered and received a

number of reports featuring mystifying but seemingly genuine creatures variously

likened to winged toads, flying toads, or flying frogs that had been reported

from the U.K., France, and the Far East, yet which were decidedly different

from the famous flying or (more accurately) gliding frogs Rhacophorus

spp. of southeast Asia (which are wingless but after leaping from trees can

glide through the air for short periods by virtue of their toes' enlarged

interdigital webbing membranes acting as mini-parachutes).

A real-life flying frog in gliding

mode, as depicted on the cover of the Czech edition of my book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings (© Dr Karl Shuker)

So bizarre in form

are these creatures that they remain unidentified, decades or even centuries

after they were first reported. To read about them, check out my new book here.

Just a few days after I sent my book's final version to the publishers and thence to the printers for publication, I received from English bibliographical crypto-sleuth Richard Muirhead (thanks, Richard!) a fascinating newspaper report concerning what was described in it as a flying toad, but this time from the USA. Sadly, the downside was that it was too late for me to include this report in my book, but the upside was that after reading it I felt confident that unlike those in my book, this was one flying toad whose identity I could definitely lay bare.

My Balinese flying toad, carved from wood and brightly painted (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Just a few days after I sent my book's final version to the publishers and thence to the printers for publication, I received from English bibliographical crypto-sleuth Richard Muirhead (thanks, Richard!) a fascinating newspaper report concerning what was described in it as a flying toad, but this time from the USA. Sadly, the downside was that it was too late for me to include this report in my book, but the upside was that after reading it I felt confident that unlike those in my book, this was one flying toad whose identity I could definitely lay bare.

Here is the text (there were no images) of the report

in question, which had appeared on 28 August 1869 in an English newspaper

called the Grantham Journal:

"An American paper

reports the capture of a flying toad at Cape Henry [on Virginia's Atlantic

shore] a few days ago, and says it is now in Washington. It is of most singular

conformation and of beautiful variated hues, measuring about six inches in

length, with a perfectly flat, bony back, eyes wide spaced and in the centre of

a…mouth, and fins as large as wings about the centre of the body on each side."

The reference to the

specimen being "now in Washington" suggests that following its

capture it was sent to the Smithsonian Institution, so that would seem to be

the most promising place to contact in the hope of uncovering further

information concerning this strange creature. Having said that, however, I feel

sure that we can ascertain its identity with a high degree of probability just from

the report alone. For although the above account may sound truly bizarre, it is

in fact an accurate description of an extremely distinctive and quite

spectacular species of small marine fish – Dactylopterus volitans, the

so-called flying gurnard.

Atlantic flying

gurnard Dactylopterus volitans with its beautiful wing-like pectoral

fins outstretched (© Beckmannjan/Wikipedia GFDL)

Flying gurnards, of which

there are several species, are exceptionally difficult to classify. Measuring

up to 1 ft long, the Atlantic flying gurnard Dactylopterus volitans

(whose distribution along the USA's eastern coast includes Virginia, where the

so-called flying toad was captured) and the comparably-sized starry flying

gurnard Dactyloptena (=Daicocus) peterseni from the

Indo-Pacific are among the most familiar representatives of these curious

fishes. Over the course of time, they have been variously categorised with the

true gurnards, the sea-robins, and the sea-horses, but are nowadays generally housed

in their own suborder within the taxonomic order Scorpaeniformes, or even within

an order entirely to themselves. Apart from Dactylopterus volitans,

flying gurnards are mostly of Indo-Pacific distribution, and are benthic

(bottom-dwelling) species.

Note the

unquestionably toad-like appearance of the flying gurnard's head and face (©

Marco Chang/Flickr)

Superficially similar to

true gurnards but distinguished from them anatomically by subtle differences in

the arrangement of their head bones and the spines of their pectoral fins, flying

gurnards are characterised by their large, bulky heads encased in hard bone and

surprisingly toad-like in appearance when viewed both in profile and face-on;

their brightly-coloured, box-shaped bodies, dappled with multi-hued spots; and,

above all else, by the enormously enlarged pectoral fins of the adults,

expanded like giant, heavily-ribbed fans or paired wings.

Compare this description

with that of the 'flying toad' of Cape Henry and it seems evident that they are

referring to one and the same creature.

But this is not the only

mystery of natural history to feature the flying gurnards. Even more perplexing

is whether, in spite of their longstanding 'flying' epithet, these wing-finned

fishes ever actually do become airborne.

Flying gurnards, depicted airborne in a

chromolithograph from 1893 – but can they really glide through the air?

Back in 1991, I investigated

this curious riddle in the first of my trilogy of extraordinary animals books – Extraordinary Animals Worldwide; and returned

to it 16 years later in my trilogy's second book – Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007). Here

is what I wrote and revealed in that latter book:

Records dating back as far as Greek and

Roman times tell of how these attractive fishes are able to launch themselves

out of the water and glide over the surface for a notable distance, just like

the better known ‘flying fishes’ (Exocoetus spp.), before plunging back

down into the sea again, and even compared their gliding with that of swallows.

According to early authorities such as Salvianus, Belon, and Rondelet, the

reason for this behaviour was to escape predators in the water (even though by

leaping out of it they surely exposed themselves to the danger of being swooped

upon by gulls and other seabirds).

A true flying fish taking off (public domain)

Yet whatever the reason for gliding, for a long time there seemed no reason to doubt that they did glide. There are numerous reports on record from schooners and other ocean-going vessels, recounting the impressive sight of whole schools of these colourful sea creatures suddenly breaking through the surface of the sea and gliding for up to 300 ft or more on their varicoloured outstretched pectorals, before sinking back beneath the waves, only to be replaced by a second school, and then by a third, and so on, in a breathtaking display of piscean aerobatics.

One of the chief reasons for subsequent

scepticism arose from a grave error by naturalist H.N. Moseley and fellow

researchers aboard the late 19th Century research vessel Challenger.

Their reports testified to the frequent occurrence of schools of flying

gurnards rising up out of the water and gliding past on wing-like pectorals;

tragically, however, it was later shown that they had misidentified these

fishes. Instead of flying gurnards, they had been the true Exocoetus flying

fishes! Naturally, this did not help the flying gurnard’s case. Since then, the

general consensus has been that flying gurnards are too heavy and cumbersome

even to lift themselves up out of the water, much less to soar above it. Not

everyone, however, is convinced by this.

During communications with distinguished

ichthyologist Dr Humphrey Greenwood, I learnt that he once saw a single flying

gurnard (probably a Dactyloptena orientalis) glide up out of the

disturbed waters at the bows of a small tug moving slowly in shallow water

(about 10 ft deep) off the Indo-Pacific island of Inhaca, in Maputo Bay. Dr

Greenwood stressed that when the fish emerged, it did become airborne, and that

its passage through the air seemed to be supported by its spread pectoral fins

(spanning roughly 8 in). The movement genuinely appeared to be a controlled

glide, tracing more of a gentle parabola than the sharp, uncontrolled,

haphazard leap out of and back into the water that many authorities consider to

be the very most that could be expected of such fishes, especially benthic

types like the flying gurnards. Greenwood believes that the reason for his

fish’s uncharacteristic occurrence in shallow water was most likely disturbance

by the noisy, water-displacing passage of the tug, the fish ascending to the

sea’s surface as an escape response.

Correspondingly, it seems reasonable to

assume that although the flying gurnards’ lifestyle is one that does not

normally involve gliding, their pectoral fins can sustain it if some exceptional

circumstance should arise to warrant such activity. Yet until precisely

monitored (preferably filmed) observations of flying gurnards engaged in

purposeful gliding are (if ever) obtained, it is likely that their aerial

capability will continue to be dismissed as (in every sense of the expression)

a pure flight of fancy.

A flying toad of the photoshopped variety!

For more cases and information concerning supposed winged toads and other alleged amphibians of the aerial variety, and to complete your extraordinary animals trilogy, be sure to check out my newly-published book The Menagerie of Marvels: A Third Compendium of Extraordinary Animals.

No comments:

Post a Comment