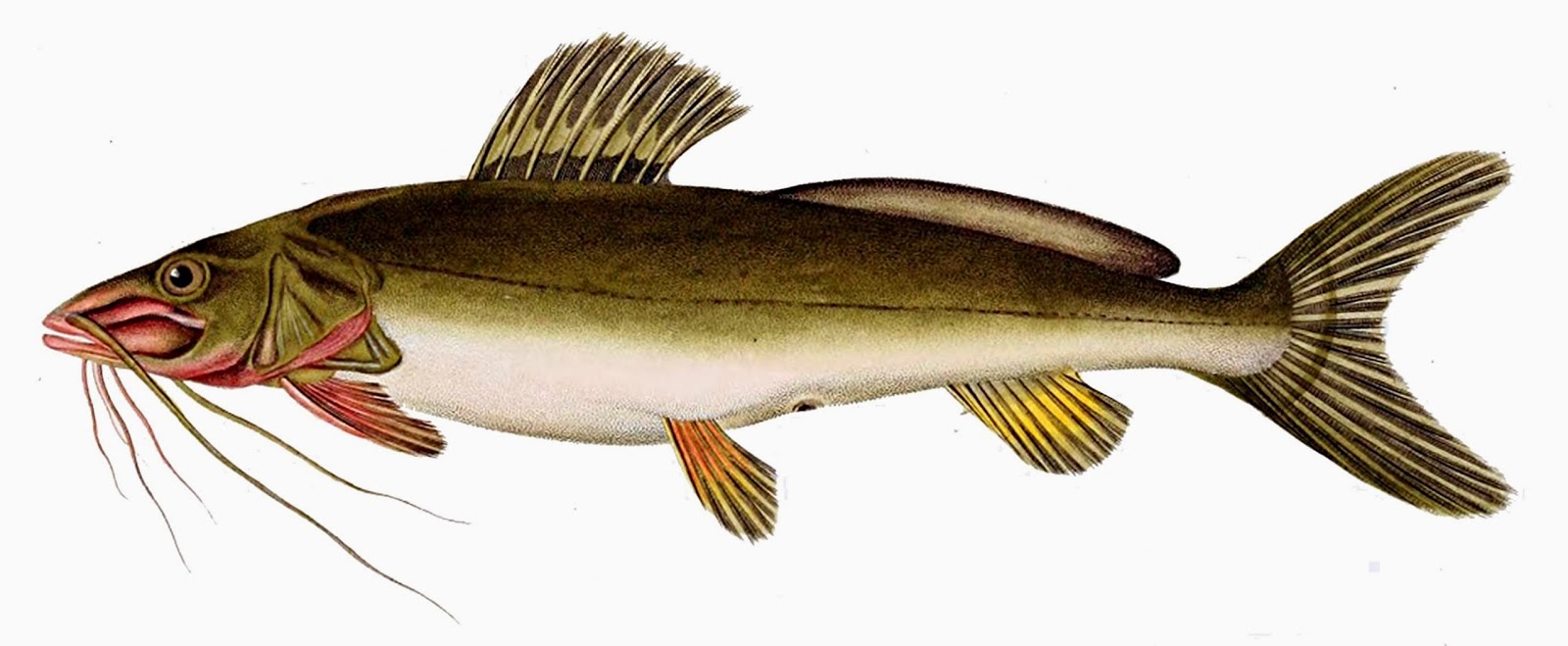

Reconstruction

of the likely appearance of the Indian swamp adder, aka the speckled band (©

Tim Morris)

According to a number of Sherlockian scholars, today, 6 January, is Sherlock Holmes's birthday - so it seemed a very appropriate day upon which to present the following ShukerNature investigation of mine.

During his

numerous cases, the famous if fictitious consulting detective Sherlock Holmes,

created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, encountered a number of extraordinary

creatures – the hound of the Baskervilles, the giant rat of Sumatra (click here for my ShukerNature article re this monstrous rodent), an unknown

species of worm that sent its observer insane, and an exceptionally venomous,

enigmatic Indian serpent referred to obliquely by one of its victims as the

speckled band. But does the latter snake truly exist, and, if so, what is it?

HOW

SHERLOCK HOLMES DEFEATED THE SPECKLED BAND

First appearing in February 1892 within the

Strand Magazine as a stand-alone Sherlock Holmes short story, 'The

Adventure of the Speckled Band' is one of twelve that were then collected

together and republished later that same year within a compilation volume

entitled 'The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes'. (It was also adapted by Conan

Doyle into a stage play called The Stoner Case, with the production opening

at London’s Adelphi Theatre in June 1910.)

This particular story

tells of how Dr Grimesby Roylott, a very aggressive medical doctor heavily in

debt but with two heiress step-daughters, murdered one of them, Julia Stoner,

using a most ingenious, undetectable modus operandi that he was now also secretly

attempting to use upon his other step-daughter, Helen Stoner. If successful, he

would retain all of their money. Although Helen does not realise that her own

life is in imminent danger, she feels sufficiently disturbed by the mysterious

death of her sister, who was heard to cry out "It was the band! The

speckled band!" immediately before dying, to engage Sherlock Holmes to

investigate.

Holmes,

Watson, and Helen Stoner, depicted by Sidney Paget

Assisted by his

faithful companion Dr Watson, it is Holmes who then discovers that Roylott had

murdered Julia (and was now seeking to do the same to Helen) using an

exceedingly venomous species of Indian snake referred to by Holmes as a swamp

adder, whose blotch-patterned body was the speckled band that the doomed

Julia's last words had succinctly described.

Sherlock

Holmes striking out at the swamp adder, depicted by Sidney Paget

Happily, after

hiding in Helen's bedroom they are able to thwart the deadly serpent, which,

angered by Holmes's attack upon it with a cane, swiftly flees from whence it

had come - back into the bedroom of its owner, Roylott. When Holmes and Watson then

enter Roylott's room, they find him dead, with what looks at first like a

speckled band wrapped around his head. Upon cautious, closer inspection,

however, this proves to be the swamp adder, which in its enraged, still-agitated

state had turned upon Roylott, killing him with a single lethal, fast-acting bite.

Waxwork

of Dr Grimesby Roylott with swamp adder around his head, at London's

Sherlock Holmes Museum (public

domain, from Wikipedia)

THE

INDIAN SWAMP ADDER – IN SEARCH OF AN IDENTITY

In the story,

the swamp adder was referred to by Holmes as "the deadliest snake in India", but what

exactly is a swamp adder? No known species of snake in India – or anywhere

else, for that matter - is ever referred to by that particular name. Unfortunately,

however, the story contains only the sparsest of morphological and behavioural details

concerning this enigmatic serpent.

Its body is

yellow, patterned with brownish speckles, and probably around 1 m long but

fairly slender if it resembles a band and can wrap itself around a man's head.

Its own head is squat and diamond-shaped, and its neck is puffed. Its hiss is

said to be "a very gentle, soothing sound, like that of a small jet of

steam escaping continually from a kettle", but according to Holmes its

venom is so toxic that it kills in 10 seconds. Yet its fangs apparently leave

such tiny, inconspicuous puncture wounds when it bites its victim that they

were not noticed by the coroner who examined Julia Stoner's body. For according

to a statement made by her sister Helen to Holmes, no marks had been found upon

Jane by the coroner.

Down through the

years, this intriguing reptilian mystery has engaged the attention of many

scholars, of Sherlockian and herpetological expertise alike, with a number of

different identities proposed for the perplexing Indian swamp adder.

IS

THE SWAMP ADDER TRULY A SPECIES OF VIPER?

The most popular

identity is the very venomous tic polonga or Russell's viper Daboia russelii,

a large terrestrial species found throughout the Indian subcontinent. Due in no

small way to its frequent proximity to human habitation, this infamous species

is responsible for more deaths and incidents involving snake-bite than any

other venomous snake in the entire region. Up to 1.66 m long, its relatively

slender, brown-blotched, yellow-tan body does recall the 'speckled band'

description for the mystifying swamp adder. Also, as its triangular head is

distinct from its neck, when viewed at certain angles its head and the

beginning of its neck can collectively yield a diamond shape.

Russell's

viper (© gupt_sumeet/Wikipedia)

However, like

that of all vipers, this species' venom is haemotoxic, which is relatively

slow-acting compared to the much more rapid-acting neurotoxin produced by

elapids. And far from being gentle and soothing in sound, its hiss is famously

loud – among the loudest hisses produced by any species of snake. In addition,

its preferred habit is dry, grassy, open terrain; it actively avoids humid,

swampy, marshy areas. Clearly, therefore, the Russell's viper is unlikely ever

to be referred to as a swamp adder.

Saw-scaled

viper depicted in a painting from 1878

Two other

viperid candidates that have also been proposed on occasion are the Indian

saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus (also known as the little Indian viper)

and the temple viper Tropidolaemus wagleri. However, the former species does

not exceed 80 cm (and only rarely exceeds 60 cm), and does not possess either

the speckled patterning or the diamond-shaped head of the swamp viper. Also, it

is an inhabitant of dry, rocky terrain, not humid swamps. As for the temple

viper: this pit viper species is bigger than the saw-scaled viper, with females

growing up to 1 m long. It also exhibits a range of colour and pattern

variations, but none of them includes that of the swamp adder. And, crucially,

it is not native to India anyway (its

distribution being confined to southeastern Asia).

Temple

viper, green variety (© Bonvallite/Wikipedia)

Neither is the

African puff adder Bitis arietans, yet this too has been suggested by

some as a putative swamp adder. Quite apart from its fundamental zoogeographical

difference, however, the puff adder is renowned for the loudness (as opposed to

the gentleness) of its hiss, and for the savagery of its bite, whose fangs can

cause severe physical trauma in addition to their envenoming effects. This is a

very far cry from the very inconspicuous puncture marks attributed to the swamp

adder.

Puff

adder ready to strike

Another

exclusively African species that has been considered is the rhinoceros viper Bitis

nasicornis, named after its instantly noticeable horn-like scales on the

end of its nose – features conspicuous only by their absence in the swamp

adder's description!

Rhinoceros

viper (© Dawson/Wikipedia)

Exit the puff

adder and the rhinoceros viper.

COBRAS,

BOAS, AND OTHER UNLIKELY SWAMP ADDER EXPLANATIONS

The common

Indian cobra Naja naja is a much-touted elapid candidate for the swamp

adder's identity, particularly by the late Richard Lancelyn Green and certain

other Sherlockian scholars and devotees. Certainly, its neurotoxin would act

more swiftly than the haemotoxin of any viper or adder. Nevertheless, it is

difficult to conceive how so familiar and distinctive a snake as this one,

perhaps the best known serpent species in all of India, could possibly be one

and the same as the mysterious swamp adder. True, the latter's puffed neck may

be an allusion to the cobra's hood (or at least a cobra-reminiscent neck

expansion), but the Indian cobra lacks the characteristic speckled patterning

of the swamp adder, and its head is not diamond-shaped. In fact, it looks

nothing remotely like any type of adder or viper.

Indian

cobras and snake charmers, depicted in a lithograph from 1890

Even more

implausible ophidian identities that have been raised at one time or another

include the decidedly non-venomous, non-Asian boa constrictor Boa

constrictor; the extremely venomous but irrefutably Australian taipan Oxyuranus

scutellatus; and a species of krait.

Fundamental zoogeographical differences

aside, the boa constrictor notion no doubt stems from a suggestion that Conan

Doyle was inspired to write his story having read a story entitled 'Called on

by a Boa Constrictor: A West African Adventure', which had appeared in Cassell’s

Saturday Journal, published in February 1891. Staying in a ramshackle cabin

belonging to a Portuguese trader, the narrator reveals his horror at being

woken by a massive snake dangling over him. Paralysed by fear, he cannot cry

out, but he spots a bell hanging off a beam within reach. Although the cord to

ring it has rotted away, the narrator discloses how he manages to summon help

by hitting it with a stick.

Nor is this the only link between the

speckled band mystery and a species of constricting snake. In his stage production of this story, The Stoner Case,

Conan Doyle cast an African rock python Python sebae as the speckled

band. Unfortunately, this particular snake did not excel in the role. Conan

Doyle later wrote:

"We had a fine rock boa [sic] to play the title-rôle, a

snake which was the pride of my heart, so one can imagine my disgust when I saw

that one critic ended his disparaging review by the words, "The crisis

of the play was produced by the appearance of a palpably artificial

serpent." I was inclined to offer him a goodly sum if he would

undertake to go to bed with it."

As for a krait:

it is true that certain species are Indian, all are venomous (some extremely

so), and they may be encountered in damp areas. However, they differ

dramatically from the speckle-patterned swamp adder with its squat

diamond-shaped head by virtue of their boldly striped markings and their sleek,

slender head.

Banded

krait, depicted in a painting from 1878

Kraits are also

extremely timid, often preferring to conceal their head amid their coils, drawing

attention away from it by vigorously twitching their tail instead, thus readily

contrasting with the swamp adder's active, undisguised aggression.

Of course, there

is the remote, but not impossible, prospect that the swamp adder is not a snake

at all...

WHEN

IS A SNAKE NOT A SNAKE? WHEN IT'S A LEGLESS LIZARD?

Certainly, there

are various peculiar behavioural characteristics claimed for the swamp adder

that cause problems when attempting to reconcile it with any species of snake.

In 'The Adventure of the Speckled Band', the swamp adder reaches its victim, Julia

Stoner, by crawling through a ventilation shaft linking her bedroom with that

of her murderous step-father Roylott next door, and then down a rope pull

hanging directly over the bed in which she is sleeping. After it has bitten

her, the snake crawls up the rope again and back through the shaft, in response

to Roylott (in his bedroom) having alerted it by whistling to it!

First and

foremost: unless it were an exceptionally adept arboreal species, would the

swamp adder be able to climb up a vertical length of rope? And secondly: as

snakes are famously insensitive aurally to airborne vibrations, how could it

possibly be able to hear Roylott's whistling?

Consequently,

there has been speculation that the swamp adder is not a snake at all, but

conceivably a legless or near-legless species of lizard, belonging to the skink

family. There are indeed several species of skink fitting this description, and

which therefore do appear remarkably serpentine on first glance, especially to

non-specialist observers. Some such lizards, moreover are native to India.

Chalcides

chalcides, a near-limbless skink

And skinks,

unlike snakes, can definitely hear airborne vibrations. Whether they are adept

at climbing up and down vertical ropes is another matter, but in any case this

otherwise ingenious non-ophidian identity is fatally scuppered by the

incontestable fact that skinks are entirely non-venomous. Consequently, if a

skink bit someone, they would not be poisoned by it.

The only

sensible conclusion that can be drawn from this article's analysis of the

varied candidates on offer is that the swamp adder is an entirely fictitious,

invented creature that Conan Doyle created specifically in order to supply his

story with a supremely formidable reptilian opponent for pitting against

Sherlock Holmes – an ophidian Moriarty, no less. Aspects of its appearance may

well have been inspired by real snakes, such as the Russell's viper's body

colouration and markings, and the rapid action of the cobra's neurotoxin, but

the swamp adder has no basis in reality as a valid, discrete species in its own

right.

Russell's

viper, depicted in a drawing from 1878

However, this is

not quite the end of this literary serpent's identity crisis. There is still

one more identity to consider, the most astonishing of all – not only because

of its particular nature but also because of where (and how) it appeared within

the scientific literature.

SWAMP

ADDER AND MONGOLIAN DEATH WORM – ONE AND THE SAME CREATURE?

In a previous ShukerNature

article (click here), I documented an

extraordinary mystery beast said to inhabit the Gobi Desert and known as

the Mongolian death worm. According to the nomads inhabiting this vast expanse

of sand, the death worm can spit forth a deadly, corrosive venom, and can also

kill instantly if touched by a mechanism that sounds uncannily like

electrocution. No specimen of this reputedly lethal animal has ever been made

available for scientific analysis, and it may well simply be folkloric, or even

if genuine merely a harmless amphisbaenian or similar reptile whose murderous

talents owe more to local superstition than to physiological capability.

Reconstruction

of the likely appearance of the Mongolian death worm (© Ivan Mackerle)

In 1956,

however, the death worm was sensationally linked to the swamp adder as the

latter's bona fide identity. Not only that, it was even given a formal

scientific name. The publication in which all of this appeared was a very

comprehensive 238-page monograph of the lizard family Helodermatidae, which

houses those two famously venomous New World species, the

Gila monster Heloderma suspectum and the beaded lizard H. horridum.

Published in no less august a scientific journal than the Bulletin of the

American Museum of Natural History, and entitled 'The Gila Monster and Its

Allies', it was authored by renowned herpetologists Drs Charles M. Bogert and

Rafael Martín Del Campo, and as would be expected from such authors writing in

such a journal, the paper was totally scientific and serious throughout – or

was it?

Tucked away on

pages 206-209, in a section entitled 'Hybrid Origin', was a mind-boggling claim

that according to a paper by snake authority Dr Laurence M. Klauber, a hybrid

creature had been successfully produced in a laboratory in Calcutta, India, by

crossbreeding cobras with Gila monsters! Not only that, some of these

astounding hybrids had subsequently escaped, with various of their descendants

yielding the allegedly highly venomous Indian lizard called the bis-cobra (featured

in a forthcoming book of mine), and other descendants yielding the Mongolian

death worm in the Gobi Desert!

Moreover, and

equally dramatic, this selfsame hybrid was also claimed to be the identity of

the swamp adder in Conan Doyle's Speckled Band story. A quadrupedal lizard with

the venomous potency of a cobra would, in the opinion of Klauber, reconcile all

of the problems faced when attempting to identify the swamp adder with any of

the more traditional identities that have been proposed.

Accordingly, in

their monograph Bogert and Martín Del Campo put forward an official binomial

name for this hybrid, which was clearly now breeding true and therefore, they

felt, fully deserved one. They dubbed it Sampoderma allergorhaihorhai –

'Sampoderma' combining 'samp' (a Hindustani name for 'snake') and the Gila

monster's generic name, Heloderma; and 'allergorhaihorhai' being a name

applied by the Gobi nomads to the death worm. They even included an ideogram of

the hybrid's appearance.

Ideogram

of Sampoderma allergorhaihorhai (© Derry Bogert/Bulletin of the

American Museum of Natural History - reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Needless to say,

however, the concept of successful hybridisation between a cobra and a Gila

monster is so outlandish that there was clearly more – or less – to the claims

of Bogert and Martín Del Campo than met the eye, as a closer study of this

particular section of their monograph soon revealed. (Moreover, the bis-cobra

is also a red herring, figuratively if not taxonomically, because in reality it

is a harmless varanid that superstitious folklore has conferred all manner of

venomous traits upon.) For although Klauber was indeed a real-life

herpetological authority and his paper regarding the hybrid also existed, it

had not been published in any scientific journal but instead within an issue

from 1948 of the Baker Street Journal.

This was a

periodical devoted entirely to the fictional world contained within the stories

of Sherlock Holmes, and included much imaginative and entertaining but entirely

theoretical speculation and extrapolation regarding various aspects of these

stories' plots, characters, etc. And indeed, in his paper Klauber refers to

Holmes, Watson, and the nefarious Dr Roylott as real persons, naming Roylott as

the creator of the cobra x Gila monster hybrid. In short, it was all entirely

tongue-in-cheek, not to be taken in any way seriously.

As this is

instantly apparent from reading Klauber's paper, why, therefore, had Bogert and

Martín Del Campo included the fictitious hybrid in a sober, ostensibly factual

manner within their otherwise entirely literal, highly authoritative monograph?

According to Daniel D. Beck writing in his own major work, Biology of Gila

Monsters and Beaded Lizards (2004), it was a prank by Bogert that was meant

to poke fun at one of his "stodgy" colleagues at the American Museum of Natural

History.

Beaded

lizards – closest living relative of the Gila monster

Whatever the

reason, there is no doubt at all that equating it even in jest with the

Mongolian death worm yielded for the dreaded Indian swamp adder (aka the

speckled band) an identity so extraordinary that even the great Sherlock Holmes

himself may well have been hard-pressed to deduce it!

Sherlock

Holmes, depicted by Sidney Paget

NB - all non-credited illustrations included in this ShukerNature article are (to the best of my knowledge) in the public domain.