With my very own - but totally unfiendish! - Hallowe'en cat (Dr Karl Shuker)

In Asia, belief in vampire cats is still very much apparent. One of the most feared examples is the Bengalese chordewa, the bane of a hill-frequenting tribe known as the Oraons. According to their traditional lore, the chordewa is a witch whose soul can temporarily leave her body and assume the guise of a black-furred vampire cat. While in this form, it seeks out victims among the tribe's sick and dying, and lays claim to them by licking their lips or consuming their food. The chordewa's power will be assuaged, however, if her feline-shaped soul can be captured, thereby preventing it from re-entering her body, which sinks into a coma and remains in this state until (if ever) her soul returns to it.

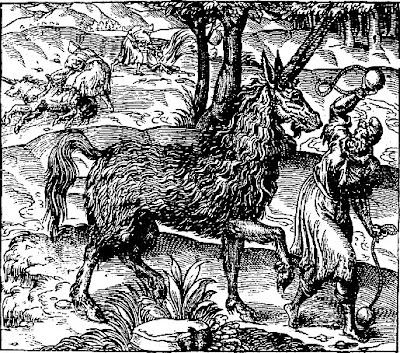

Even more deceptive but equally deadly is the Japanese vampire cat. This feline demon can assume the form of a beautiful maiden to seduce an unsuspecting man and drain him of his life, imperceptibly but inexorably, night after night - until he eventually becomes an inanimate husk. Happily, this dire spirit-beast can be recognised when spied in its true state, for a vampire cat cannot disguise the fact that it possesses not one tail but two.

Japanese vampire cat

Japanese vampire cat

One famous Japanese legend tells of how the Prince of Hizen's favourite concubine, the lady O Toyo, was secretly strangled by a vampire cat who then assumed her form, and took her place at the unsuspecting prince's side. In the weeks that followed this surreptitious substitution, however, his friends and courtiers became alarmed to see that the prince was becoming ever paler and and weaker, especially at night, as if his very life-force was somehow being drained away. But how - and by whom?

Finally, one of the prince's most loyal soldiers kept watch over his master's bed chamber, and spied the false O Toyo approach the sleeping man - ready to change back into a vampire cat and imbibe his blood, as it had been doing each night since it had killed the real O Toyo. Sensing the soldier's presence, however, this feline female paused, but the soldier had accurately guessed her evil intent and leapt forward to slay her. Instantly, the false O Toyo became a vampire cat again, and fled away into the mountains. Some say that it was later killed there, but others believe that it survived, and will one day have its revenge. There have even been claimed sightings of this vampire cat; the most recent was in 1929.

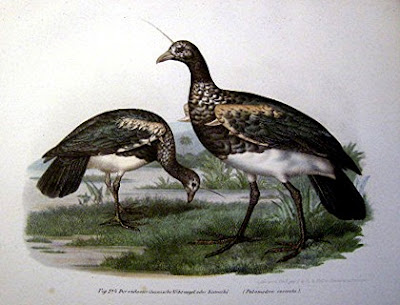

Rather less easy to espy is the Indian devil cat, which can haunt homes like a feline poltergeist, for this creature is normally invisible. However, its presence can be readily detected, due to its spine-chilling shrieks, likened to a bloodcurdling fusion of a cat's yowling cry with the ear-splitting scream of a peacock! One or more of these evil entities will sometimes invade a house, much to the consternation and despair of its inhabitants, or will take up residence on its roof and regale the people below with hideous eldritch screeching. Fortunately, if a house troubled by a devil cat is sprinkled with holy water and blessed by a priest, its shrill sounds will be heard there no more.

This post is excerpted from my forthcoming book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery

In Asia, belief in vampire cats is still very much apparent. One of the most feared examples is the Bengalese chordewa, the bane of a hill-frequenting tribe known as the Oraons. According to their traditional lore, the chordewa is a witch whose soul can temporarily leave her body and assume the guise of a black-furred vampire cat. While in this form, it seeks out victims among the tribe's sick and dying, and lays claim to them by licking their lips or consuming their food. The chordewa's power will be assuaged, however, if her feline-shaped soul can be captured, thereby preventing it from re-entering her body, which sinks into a coma and remains in this state until (if ever) her soul returns to it.

Even more deceptive but equally deadly is the Japanese vampire cat. This feline demon can assume the form of a beautiful maiden to seduce an unsuspecting man and drain him of his life, imperceptibly but inexorably, night after night - until he eventually becomes an inanimate husk. Happily, this dire spirit-beast can be recognised when spied in its true state, for a vampire cat cannot disguise the fact that it possesses not one tail but two.

Japanese vampire cat

Japanese vampire catOne famous Japanese legend tells of how the Prince of Hizen's favourite concubine, the lady O Toyo, was secretly strangled by a vampire cat who then assumed her form, and took her place at the unsuspecting prince's side. In the weeks that followed this surreptitious substitution, however, his friends and courtiers became alarmed to see that the prince was becoming ever paler and and weaker, especially at night, as if his very life-force was somehow being drained away. But how - and by whom?

Finally, one of the prince's most loyal soldiers kept watch over his master's bed chamber, and spied the false O Toyo approach the sleeping man - ready to change back into a vampire cat and imbibe his blood, as it had been doing each night since it had killed the real O Toyo. Sensing the soldier's presence, however, this feline female paused, but the soldier had accurately guessed her evil intent and leapt forward to slay her. Instantly, the false O Toyo became a vampire cat again, and fled away into the mountains. Some say that it was later killed there, but others believe that it survived, and will one day have its revenge. There have even been claimed sightings of this vampire cat; the most recent was in 1929.

Rather less easy to espy is the Indian devil cat, which can haunt homes like a feline poltergeist, for this creature is normally invisible. However, its presence can be readily detected, due to its spine-chilling shrieks, likened to a bloodcurdling fusion of a cat's yowling cry with the ear-splitting scream of a peacock! One or more of these evil entities will sometimes invade a house, much to the consternation and despair of its inhabitants, or will take up residence on its roof and regale the people below with hideous eldritch screeching. Fortunately, if a house troubled by a devil cat is sprinkled with holy water and blessed by a priest, its shrill sounds will be heard there no more.

This post is excerpted from my forthcoming book Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery