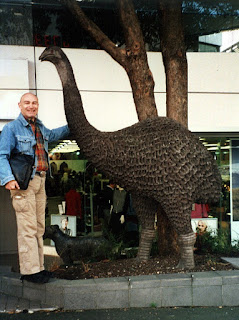

Photographed in 2006 alongside the sturdy,

relatively short-legged Aotea Moa Statue, designed and sculpted (in concrete?) by

Robin Coleman of Marton, and standing outside the Aotea New Zealand Souvenir

Store on Queen Street in the centre of Auckland, on North Island, New Zealand –

might it have been inspired by a Pachyornis species? (© Dr Karl Shuker)

It is well established that the extinct moas constituted a group

of ratites exclusive to New Zealand - which is why

the little-known tale of Australia's unique Queensland moa is worth

retelling. So here it is.

In 1884, this zoogeographical heretic was christened Dinornis

queenslandiae by English-born zoologist Charles W. De Vis (at that time the

director of the Queensland Museum), in a Proceedings

of the Royal Society of Queensland paper. He based

its species on a fossilised, incomplete left femur, spotted by him in a

collection of bones from King's Creek, on Queensland's Darling Downs,

that had been presented to the museum by a Mr J. Daniels of Pilton. Naturally,

the specimen attracted great interest among ornithologists, as it extended the

moas' distribution very considerably. No longer were they a novelty of New Zealand - always

assuming, of course, that it really was a moa.

The contentious partial left femur upon which the Queensland

moa was established (Figs 1 and 2 from De Vis's Proceedings of the Royal

Society of Queensland paper, 1884 – public domain)

Over the years, however, this assumption became a much-debated

issue.

In 1893, for instance, eminent New Zealand naturalist Captain

Frederick W. Hutton deemed the bone to be from a cassowary-like species that

probably represented the common ancestor of emus and cassowaries, which are

currently classed together within the same taxonomic order, Casuariiformes (and

click here

to access my ShukerNature article documenting some very controversial

cassowaries). He documented his opinion in a Proceedings of the Linnean

Society of NSW paper.

Australian emu Dromaius novaehollandiae (top)

and double-wattled aka southern cassowary Casuarius casuarius (bottom)

(public domain)

Then in 1949 its species was readmitted to the moa brotherhood,

when Dr Walter R.B. Oliver of Wellington's Dominion Museum renamed it Pachyornis

queenslandiae in a Bulletin: Dominion Museum (New Zealand) paper. By the

early 1960s, conversely, it was back among the emus and cassowaries, when in

1963, within a Records of the South Australian Museum paper, American

ornithologist Dr Alden H. Miller (director

of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley,

for 25 years) classified it as an emu, dubbing it Dromiceius [=Dromaius]

queenslandiae. It seemed as if this contentious species would be

spending the rest of time ricocheting from one ratite family to another - but

then came the study that finally brought its taxonomic tribulations to a

long-awaited end.

This was when, in April 1967, osteologist Ronald J. Scarlett

from New Zealand's Canterbury Museum examined the Queensland moa's femur and

revealed that it was indeed from a Pachyornis moa, but specifically the

heavy-footed moa P. elephantopus (the presence and precise shape of a bony

femoral projection called the cnemial crest clinched this taxonomic

identification). He also paid close attention to the other bones in the

original King's Creek collection within which it had been found by De Vis back

in the 1880s.

Skeleton of the heavy-footed moa Pachyornis

elephantopus skeleton in the Naturhistorisches Museum of Basel, Switzerland

(public domain)

In so doing, Scarlett recognised that the femur was strikingly

different in general appearance and colour from the rest of this collection's

material, and clearly had not been obtained with it. In addition, his very

appreciable experience with moa bones derived from caves, Maori middens,

swamps, and other sources of such remains enabled him to reveal something even

more significant – the femur was readily identifiable as a bone originating

from a midden in New Zealand's South Island. Consequently,

it was not from Australia at all! In

1969, Scarlett documented his revelatory findings in a Memoirs of the

Queensland Museum paper.

In short, the (in)famous Queensland moa was just another

non-existent creature that had been granted a transient reality by the

evocation of inaccurate information and incomplete investigation - a mere

monster of misidentification, nothing more. Pachyornis queenslandiae -

R.I.P.!

Reconstruction

of the heavy-footed moa in life (© niaolei.org.cn – reproduced here

on a strictly educational, non-commercial Fair Use basis only for the purposes

of review)

My sincere thanks go to the late Ron Scarlett for so

kindly communicating with me regarding this once-controversial form (and other

moa mysteries) during the 1990s, and for bringing his study and published paper

concerning it to my attention.

This ShukerNature article is excerpted and expanded

from my book The Beasts That Hide From Man.

Alongside a life-sized statue carved

in 2004 by Frank Triggs of the giant moa Dinornis at Chester Zoo,

England, in 2013 (© Dr Karl Shuker)