The minhocão as envisaged by Lance Bradshaw (Lance Bradshaw)

The minhocão as envisaged by Lance Bradshaw (Lance Bradshaw)

I was very interested to read Richard Freeman’s recent blogs review on the CFZ bloggo, because one of them mentioned by him discusses the possibility that a South American subterranean cryptid known as the minhocão is a giant lungfish. This is a very early suggestion, long abandoned, but reminds me of when I first suggested a new identity for this cryptid back in 1995 within my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors - namely, a giant caecilian. Prior to then, the prevailing view, as discussed by Dr Bernard Heuvelmans in his own book On the Track of Unknown Animals (1958), had been that it may be a surviving glyptodont – one of those tank-like, mace-tailed, prehistoric relatives of armadillos.

Following the publication of my idea, however, the caecilian theory soon supplanted the latter notion. Indeed, a year after my book had appeared in print, Heuvelmans himself abandoned his glyptodont identity for the minhocão in favour of my caecilian suggestion within his updated cryptozoological checklist - published in French in 1996 by Cryptozoologia as a special paper, and also constituting Chapter 8 of an unpublished Heuvelmans book entitled The Natural History of Hidden Animals.

Sadly, Heuvelmans failed to credit my book within his paper in relation to the caecilian identity, even though its preparation and publication had notably preceded his paper. However, I suppose I should not complain. After all, he did do me the very significant honour of sending me a personally signed copy of his paper, on the first page of which he had written:

“To Karl Shuker, the most brilliant of my disciples, B Heuvelmans” (see photo below).

And no – just in case anyone is thinking of asking – this is one cryptozoological item that I shall NOT be placing on eBay!!

Incidentally, during his many communications with me by letter (mostly) and phone in his later years, Heuvelmans came over to my way of thinking with regard to the putative identity of several cryptids, including not only my identification of the minhocão as a giant caecilian, but also the New Guinea devil pig as a palorchestid, my thoughts regarding certain mystery birds, and – returning, spookily, to giant lungfishes - my proposal that the buru was indeed a giant lungfish rather than either a lizard or a crocodile (thus relinquishing views expressed previously by him in his cryptozoological checklists). Had Heuvelmans lived longer, it would have been interesting to see how such changes of view would have been incorporated in his planned series of volumes documenting the mystery beasts of the world. Tragically, however, he was not able to complete most of them before his death, so we shall never know.

Returning to the minhocão: for those of you who may not have seen my coverage of this fascinating cryptid within my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors, here is what I wrote:

THE MINHOCÃO - AN ANOMALY IN ARMOUR

Until the close of the Pleistocene, the armadillos in South America and southern North America shared their world with a group of distant relatives called the glyptodonts. These resembled armadillos to a certain extent - but on a gigantic scale, measuring up to 13 ft long. Their body armour was also of colossal proportions, comprising as much as 20% of these animals' entire weight. Consisting of a huge domed shell of fused polygonal bony plates on their back, with a bony covering on top of their head too, it undoubtedly conferred upon these beasts a distinct similarity to an armoured tank. As for their tail, this was positively medieval - long and armour-encircled, and additionally armed in some species with a mace-like, spike-bearing ball of solid bone at the tip, which was probably used in the same way as a mace too - flailing it at potential attackers.

According to the fossil record, the glyptodonts died out around 10,000 years ago, but if they had lingered into the present, we might expect their unique appearance to be sufficiently memorable for anyone spying these animals to provide a readily recognisable description. In reality, although there is evidence on file that has at one time or another offered hope to cryptozoologists that the glyptodonts are indeed still with us, the morphological comparability between the beasts seen and bona fide glyptodonts is of very varying quality.

The inhabitants of southern Brazil and Uruguay have often spoken of anomalous, furrow-like trenches of great depth that have suddenly appeared in the ground for no apparent reason (but often near to some sizeable lake or river), and which they claim to be the work of a mysterious serpentine creature called the minhocão.

It was a paper by zoologist Prof. Auguste de Saint Hilaire, published by the American Journal of Science in 1847, that first brought the minhocão to Western attention. Revealing that its name is derived from 'minhoca' - Portuguese for 'earthworm' - he stated:

"...the monster in question absolutely resembles these worms, with this difference, that it has a visible mouth; they also add, that it is black, short, and of enormous size; that it does not rise to the surface of the water, but that it causes animals to disappear by seizing them by the belly."

In his paper, de Saint Hilaire gave several instances in which horses, cattle, and other livestock had been supposedly pulled beneath the water to their doom when fording the Rio dos Piloes and Lakes Padre Aranda and Feia in Goyaz, Brazil. He believed that the minhocão was probably a giant version of Lepidosiren, the eel-like lungfish of South America.

Thirty years after de Saint Hilaire, German zoologist Dr Fritz Müller, residing in Itajahy, southern Brazil, provided further details regarding the minhocão, when in 1877 his account of its activities appeared in the journal Zoologische Garten - later reiterated and recycled in other European publications, including the eminent English journal Nature. Here it was revealed that the channels excavated by the minhocão are so deep that the courses of entire rivers have been altered, roads and hillsides have collapsed, and orchards have fallen to the ground - and it also offered some new insights into this enigmatic excavator's morphology.

In the region of the Rio dos Papagaios, in the province of Paranà, circa 1840s:

"A black woman going to draw water from a pool near a house one morning, according to her usual practice, found the whole pool destroyed, and saw a short distance off an animal which she described as being as big as a house moving off along the ground. The people whom she summoned to see the monster were too late, and found only traces of the animal, which had apparently plunged over a neighbouring cliff into deep water. In the same district a young man saw a huge pine suddenly overturned, when there was no wind and no one to cut it. On hastening up to discover the cause, he found the surrounding earth in movement, and an enormous worm-like black animal in the middle of it, about twenty-five metres [75 ft] long, and with two horns on its head."

In 1849, Lebino José dos Santos, a wealthy proprietor, was travelling near Arapehy in Uruguay when he learnt about a dead minhocão to be seen a few miles off, which had become wedged into a narrow cleft of rock and consequently died. Its skin was said to be: "...as thick as the bark of a pine-tree, and formed of hard scales like those of an armadillo".

And in or around 1870, one of these beasts visited the environs of Lages, Brazil:

"Francisco de Amaral Varella, when about ten kilometres distant from that town, saw lying on the bank of the Rio das Caveiras a strange animal of gigantic size, nearly one metre in thickness, not very long, and with a snout like a pig, but whether it had legs or not he could not tell. He did not dare to seize it alone, and whilst calling his neighbours to his assistance, it vanished, not without leaving palpable marks behind it in the shape of a trench as it disappeared under the earth."

In a detailed letter, published by the Gaceta de Nicaragua (10 March 1866), Paulino Montenegro included accounts of a similar creature from Nicaragua. Said to be covered with a skin clad in scales or plates, it: "...is described in general as a large snake, and called 'sierpe,' on account of its extraordinary size, and living in chaquites [pools or ponds]".

In his summary of this fascinating cryptozoological case, Nature's editor offered two possible identities for the minhocão. One, echoing de Saint Hilaire, was a giant lungfish. The other, which no doubt by virtue of its more sensational potential has attracted much more attention during subsequent years, was a living glyptodont.

Fossil skeleton of a glyptodont, showing its extraordinary degree of body armour (Dr Karl Shuker)

I have always viewed this latter theory with more than a little scepticism, for several reasons. First and foremost, I cannot believe that anyone would liken a beast as bulky and tank-like as a glyptodont, with a domed carapace on its back, to a giant worm or snake. Anything less serpentine than a glyptodont would be hard to imagine! In contrast,

Lepidosiren is a notably elongate, anguinine (and anguilline) beast.

Although the description of horns and upturned nose could refer to the ears and snout of a glyptodont, it could equally apply to the slender, anteriorly-positioned pectoral fins of Lepidosiren, which also has a somewhat pig-like snout.

Another problem with the glyptodont identity arises when contemplating the exceedingly fossorial (burrowing) nature of the minhocão. It seems extremely unlikely that anything bearing such an immense amount of body armour - evidently for protection from attack by predators - would have either the need or the inclination for a fossorial mode of existence.

Creatures sharing this lifestyle, such as earthworms and moles, are conspicuously devoid of body armour - because they are not likely to encounter predators as frequently as if they spent their lives on the surface, and also because such armour would greatly impede burrowing activity. Fossil remains of glyptodonts provide no evidence at all for any extensive degree of underground activity. On the contrary, the excessive development of their carapace and the mace-like construction of their tail in some species clearly imply an expectation of frequent confrontation by large surface-dwelling predators equipped with fangs and claws.

True, the comparison by some eyewitnesses of the minhocão's scales to those of armadillos might seem to favour a glyptodont identity - but in reality, the reverse is true. Whereas the armadillos' armour is composed of a series of rings, in the glyptodonts those rings became fused, to yield their characteristic domed carapace, which consists of an elaborate mosaic of plates that bear no resemblance to armadillo armour. As recently as the late Pleistocene, there was a group of creatures somewhat midway in form between armadillos and glyptodonts, called pampatheres. Native to South America and also the southern U.S.A., some attained glyptodont dimensions, but their armour was of the ringed, armadillo form. Once again, however, they did not seem to be principally fossorial.

In contrast, although Lepidosiren lacks external scales this is a modern development, as the more primitive Australian lungfish Neoceratodus is profusely scaled, like ancestral lungfishes. Hence its scales do not exclude the minhocão from the lungfish identity.

Even its burrowing activity is consistent with a lungfish. Like some African lungfishes (Protopterus), during the dry season Lepidosiren aestivates - i.e. it secretes a protective cocoon around itself, and remains buried in the mud at the bottom of ponds or river beds in a self-induced state of suspended animation until the rainy season begins, whereupon it breaks out of its encapsulating cocoon and swims away.

According to the Nature report, the minhocão's deep trenches mostly appear after continued rain, and seem to start from marshes or river beds. This is just what one would expect of a giant lungfish - emerging from its subterranean seclusion with the rainy season's onset. Conversely, although armadillos can swim they only do so when required to - they are not normally aquatic; the same was probably true for the armour-laden glyptodonts.

19th-Century illustration of Lepidosiren, the South American lungfish

In short, although the size estimates for the minhocão are certainly exaggerated, taken as a whole I feel that its description is more applicable to an extremely large lungfish than to a glyptodont. I do have misgivings concerning the minhocão's supposed propensity for hauling livestock down into its watery domain - this is hardly what one might expect from a lungfish, even a giant one. In reality, however, it may simply be an effect of turbulence or a type of localised vortex for which the minhocão is being wrongly held responsible.

There is a further identity, however, that offers an even closer correspondence to the minhocão, yet which has never been previously suggested - an enormous form of caecilian.

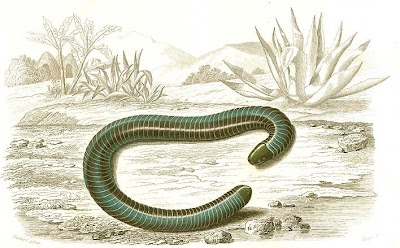

Native to the tropics of Africa, Asia, Mesoamerica, and South America, and spending virtually their entire lives burrowing underground, the caecilians are little-known limbless amphibians with outwardly segmented bodies that are extraordinarily similar in external appearance to earthworms - except for their readily visible mouth, and a pair of sensory tentacles on their head that resemble horns or ears when protruded. This description corresponds perfectly with the minhocão's as penned by de Saint Hilaire.

In addition, although their skin feels smooth and slimy, many caecilians do possess scales (unlike other modern-day amphibians), embedded within the skin.

The largest caecilian known to science, Colombia's Caecilia thompsoni, is marginally under 5 ft long. However, a giant species with well-developed scales and a capacity for excavation matching its great size would make an extremely convincing trench-gouging minhocão. And if its scaling mirrored its body's external segmentation, it would resemble the ringed armour of armadillos - clarifying why eyewitnesses liken the minhocão's scaly skin to this armour.

South America's Typhlonectes caecilians inhabit rivers and lakes, so even the minhocão's aquatic inclinations are not incompatible with these apodous amphibians. Moreover, terrestrial caecilians often emerge above ground after heavy rainstorms - another minhocão correspondence. Also, caecilians are carnivorous, and grab their prey from below - a giant species with comparable behaviour might therefore resolve reports of livestock pulled under the water when crossing rivers and lakes reputedly frequented by minhocãos.

All in all, the identity of a giant caecilian for the minhocão provides so intimate a correspondence, not only morphologically but also behaviourally, that I personally see little (if any?) reason for looking elsewhere for an explanation of this mysterious subterranean monster.

Finally, as a piece of personal trivia, the first words that I ever read in Heuvelmans’s classic book On the Track of the Unknown Animals were those quoted above from the report that described the minhocão as a creature as big as a house. That was when I first saw the Paladin paperpack edition of his book in a shop as an early teenager, opened it at random, and read the first lines that I saw. However, the concept of a beast as big as a house seemed so ludicrous that I actually put the book back on the shelf and forgot about it. Fortunately, my mother had watched me reading it, and secretly bought the book for me as a birthday present. Who knows - had she not done so, I may never have become interested in cryptozoology, my writings and researches in this field would therefore never have occurred, and I would have never experienced the lifelong fascination and enjoyment with which cryptozoology has filled me. So I have a lot to thank the minhocão – and my mother – for!

19th-Century colour engraving of a Siphonops caecilian