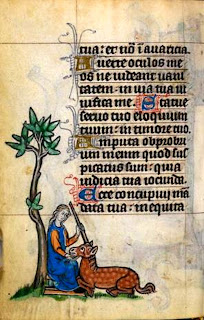

A snail-cat, depicted in the Maastricht

Hours – an illuminated devotional manuscript produced in the Netherlands during the early 1300s (public

domain)

After my exhaustive books Mystery Cats of the World (1989) and Cats of Magic, Mythology, and Mystery (2012)

were published, I might have been forgiven for thinking that I must surely have

documented a representative selection of examples for every anomalous feline

form ever recorded – but I would have been wrong, as now revealed here.

The vast assembly of curious creatures inhabiting the exquisite world wrought by generations of medieval monks and lay artists laboriously creating illuminated manuscripts of religious tracts and other devotional works is like none other anywhere in the history of zoological artwork. Alongside such stalwarts of classical Western mythology as dragons, unicorns, griffins, wildmen, and demons are all manner of truly bizarre entities that are commonly termed grotesques, for good reason. Impossible hybrids, crossbreeds, and composites of every conceivable (and inconceivable!) combination, they exhibit a surreal 'mix 'n' match' approach to morphology, deftly and effortlessly uniting the head(s) of one species with the limbs of a second, the wings of a third, and the body of who knows what from who knows where. In cases where these grotesques are more comical than frightening in form, however, they are generally referred to as drolleries.

As mentioned in previous ShukerNature blog articles

and other publications of mine, I've always been especially interested in the

more unusual contingent of animal life –real, imaginary, and those somewhere in

between (I believe the term that I'm looking for here is cryptozoology!).

Consequently, it should come as no surprise to learn that this marginalia

menagerie, i.e. the zoological monsters and monstrosities lurking amid the

margins (and sometimes cavorting among the illuminated letters too) of medieval

manuscripts, have long held a particular fascination for me, and I have spent

many long but very pleasant hours scrutinising examples from these sources as depicted

in books, articles, and online, as well as sometimes directly examining such

manuscripts themselves, thus embarking upon an entertaining if unequivocally

esoteric safari seeking cryptic creatures of the decidedly uncommon and uncanny

kind.

Thus it was that I was recently delighted to

encounter not one but three different examples of a particular mini-monster of

the marginalia variety that I had never previously spotted within the medieval

manuscripts' sequestered yet richly ornate realm of emblazoned folios and ornamented

parchment. Moreover, unlike so many others sharing its domain, this creature

exhibited a well-defined, memorable – even quaint – form, an engaging little

drollery combining the whorled shell of a snail with a cat's emerging head and

neck (sometimes its front paws too). And so, gentle reader, without further ado

I give you the snail-cat – or, should you prefer it, the cat-snail.

(Incidentally, as will be revealed later here, the artistic

motif of animals housed in snail shells is by no means confined to cats. On the

contrary, so many variations upon this molluscan theme are on record, including

humans as well as animals, that these entities even have their very own term –

malacomorphs, which translates as 'shell forms'.)

Back to the snail-cats: out of this current trio of

molluscan moggies (or feline malacomorphs, to employ the more technical moniker

for such incongruous crossbreeds), the first one to come to my attention did so

while I was browsing through the British Library's online digital version

(click here)

of the Maastricht Hours – a sumptuously illustrated version of the

once-popular book of hours. But what is a book of hours?

Back in the 12th Century, the most

common books owned by families in Europe wealthy

enough to possess such items were psalters – which normally contained the 150

psalms of the Old Testament and a liturgical calendar. They were also

beautifully illustrated by monks. Subsequently developed from the psalter was

the breviary, which contained all the liturgical texts for the Office (aka the

canonical prayers), whether said in choir or in private. During the 14th

Century, however, books of hours appeared on the scene. A type of prayer book

designed for laypeople, they largely eclipsed psalters and breviaries, and

whereas these latter works had been illuminated predominantly by monks

(monasteries being the principal producers of books back then), books of hours

could be commissioned by the wealthy from professional scribes and lay-owned

illuminators in towns and cities, and many of these beautiful works still

survive today. Here is Wikipedia's definition of the book of hours:

The book of hours

is a Christian devotional book popular in the Middle Ages. It is the most

common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript,

each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain

a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate

decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in

many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of

psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely

lavish, with full-page miniatures.

Books of hours

were usually written in Latin (the Latin name for them is horae), although

there are many entirely or partially written in vernacular European languages,

especially Dutch. The English term primer is usually now reserved for

those books written in English. Tens of thousands of books of hours have

survived to the present day, in libraries and private collections throughout

the world.

The typical book

of hours is an abbreviated form of the breviary which contained the Divine

Office recited in monasteries. It was developed for lay people who wished to

incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the

hours typically centered upon the reading of a number of psalms and other

prayers. A typical book of hours contains:

·

A Calendar of Church feasts

·

An excerpt from each of the four gospels

·

The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary

·

The fifteen Psalms of Degrees

·

The seven Penitential Psalms

·

A Litany of Saints

·

An Office for the Dead

·

The Hours of the Cross

·

Various other prayers

In its Catalogue of Illumination Manuscripts, the

British Library lists the Maastricht Hours as MS [Manuscript] Stowe 17. Written

in Latin (using Gothic script), but with a calendar and final prayers in

French, it was produced during the first quarter of the 14th Century

in Liège, the Netherlands, probably for a noblewoman, who may be represented as

a kneeling female figure in several places throughout the manuscript. It is

lavishly illustrated throughout, and its margins in particular are crammed with

all manner of grotesque beasts and other figures, often engaged in bizarre,

surprising forms of behaviour, especially so in view of their setting – a

religious devotional book.

Handsomely bound in blind-tooled blue leather, it

was once owned by Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville (1776-1839),

1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, who resided at Stowe House, near Buckingham

in Buckinghamshire, England, where it formed part of the famous Stowe Library

(hence its Stowe designation by the British Library). After a series of

intervening changes of hand, however, it was finally purchased in 1883 by the British Museum, together with 1084 other Stowe manuscripts.

The Maastricht Hours consists of 273 folios.

Like other manuscripts from the Middle Ages, it was bound without page numbers.

In relation to such manuscripts, the term 'folio' (commonly abbreviated to

'fol' or simply 'f') is used in place of 'page', and the front or top side of

each folio is referred to as the recto ('r'), with the back or under side of

each folio being the verso ('v'). Consequently, as examples of how folios are

designated in such manuscripts, the front side of a manuscript's fifth folio

would be referred to as f 5r, and the back of the manuscript's 17th

folio as f 17v. Bearing in mind that some consist of as many as 300 folios or

even more, illuminated manuscripts housed in libraries sometimes have the respective

number of each constituent folio lightly pencilled upon its recto side's

top-right corner, for ease of access to specific folios.

On f 185r of the Maastricht Hours, which

contains a prayer for the family of the book's owner, a scowling snail-cat is

clearly visible, perched upon an illuminated curl sweeping underneath the

prayer. Its shell is dextral in shape, i.e. its whorls spiral to the right, and

disproving the opinion of some writers who have suggested that perhaps

snail-cats depicted in medieval manuscripts are simply ordinary domestic cats

sitting inside empty (albeit exceedingly large!) snail shells with their head

and neck sticking out of the shell's aperture, this particular snail-cat

confirms its bona fide hybrid nature by sporting a pair of antenna-like snail

stalks on top of its head. Unlike those of real snails, however, its stalks do

not bear eyes at their tips – its eyes being set in its face instead, like

those of normal cats.

Incidentally, the specific conformation of this

snail-cat's shell is very reminiscent of a fossil ammonite shell. Who knows – perhaps one of the

illuminators working on the Maastricht Hours had seen such a specimen at some time, and incorporated its form

into his snail-cat's design.

But this is not the only shelly surprise contained

within this manuscript's folios. Several other entities of equally unexpected

shell-bearing status can also be found here, as now shown.

The Maastricht Hours snail-cat compared with a fossil shell from the common British ammonite Peltoceras; the latter illustration is from C.P. Castell's book British Mesozoic Fossils (BMNH, 1962) (public domain/©

C.P. Castell/BMNH - inclusion here strictly on Fair Use/non-commercial basis only)

The head and shoulders of a curly-headed youth(?)

emerge from a sinistral shell (its whorls spiralling to the left) at the bottom

of f 8r, as do those of an unidentified horned ungulate at the bottom of f 11r.

A bearded dextral-shelled snail-man with emerging

upper torso including arms can be seen at the bottom of f 193v:

A dextral-shelled snail-goat appears on f 222v:

And on f 272r a woman is shown dancing before a

smaller dextral-shelled snail-human whose face has been obscured by wear and

tear of the book down through the centuries.

Whoever produced the artwork for this manuscript

evidently had a serious passion for manufacturing malacomorphs!

My second snail-cat turned up in the Bibliothèque

Mazarine's MS 62, NT Épîtres de Saint Paul (originally the personal library of

Cardinal Mazarin, the celebrated Italian cardinal and diplomat who served as

Chief Minister to the French monarchy from 1642 until his death in 1661, the Bibliothèque

Mazarine is the oldest public library in France). As its title suggests, this

manuscript contains the Epistles of St Paul from the New Testament, written in the

Vulgate Latin translation. It consists of 149 folios, dates from the final

quarter of the 14th Century, and was originally owned by the Convent

of the Minimes in the village of Nigeon, located on the hill of Chaillot, near Paris.

F 70v of the Bibliothèque Mazarine's

MS 62, NT Épîtres de Saint Paul, revealing the presence of a snail-cat in the

left-hand margin (public domain)

On f 70v of this manuscript, one of the quadrants

in the elaborately illuminated margin's left-hand side contains a delightful

snail-cat, one that in sharp contrast to the distinctly unfriendly version in

the Maastricht Hours is happily smiling, is housed within a sinistral

snail shell, and is revealing its front paws. It lacks the snail horns of the Maastricht snail-cat, but its ears are unusually long and

pointed.

Close-up of the snail-cat in f 70v of

the Bibliothèque Mazarine's MS 62, NT Épîtres de Saint Paul (public domain)

As with the Maastricht Hours, moreover, its

snail-cat is not the only malacomorph drollery present in this manuscript. Browsing

through its complete collection of illuminated folios online (click here),

I also spotted a snail-griffin on f 89v whose shell is attached solely to its

haunches, with the rest of its body entirely external to it; a bearded

human-headed snail-monster on f 102v; and a strange dog-like snail-monster bearing

what resembles a reverse coxcomb upon its head on f 112.

Snail-griffin (top

left), human-headed snail-monster (top right), and dog-like coxcombed snail-monster

(bottom), from the Bibliothèque Mazarine's MS 62, NT Épîtres de Saint Paul

(public domain)

Snail-cat #3 appears in a Paris-originating book of

hours manuscript entitled Horae ad Usum Parisiensem, which dates from

the final quarter of the 15th Century, consists of 190 folios plus four

additional folios in parchment, and is written in Latin. It is held in the

National Library of France's Department of Manuscripts, but can be viewed in

its entirety online here.

Its snail-cat appears on f 187r, and like the

previous example it is smiling with front paws present outside its shell, whose

whorls spiral in a dextral configuration. Its ears are less pronounced and

pointed than those of snail-cat #2, and it lacks the snail horns of snail-cat

#1.

Whereas the illuminator of the Maastricht Hours

exhibited a definite obsession with malacomorphs, the artist responsible for

the marginalia menagerie in Horae ad Usum Parisiensem showed far more

interest in composite centaurs, depicting a wide range of forms, but only one

malacomorph other than the snail-cat. This second malacomorph is itself a

composite, combining the turbaned head, arms, and upper torso of a man with a

pair of large bat-like wings the lower torso and front paws of a leonine

creature, and a sinistral snail shell; it appears on f 46r.

During my browsing of various other illuminated

manuscripts online in recent times, I've collected a number of additional

malacomorphs, and a small selection of the more interesting and unusual ones is

presented below.

An unidentified (possibly porcine?) but unequivocally angry malacomorph appears on f 109v of esteemed Flemish author-poet Jacob van

Maerlant's manuscript Van Der Naturen Bloeme, produced in The Hague, Netherlands, in c 1350. This is in turn a free translation of

13th-Century Brabant author Thomas of Cantimpré's 20-volume magnum opus

De Natura Rerum.

The Luttrell Psalter is an illuminated manuscript

produced sometime during 1325-1340 for the wealthy Luttrell family of Irnham in

Lincolnshire, headed by Irnham's lord of the manor, Sir

Geoffrey Luttrell, who commissioned its preparation. It consists of 309 folios,

is written in Latin, and is now held in the British Library as Additional

Manuscript (Add. MS) 42130, after having been acquired by the British Museum in 1929.

It is famous for its extraordinary array of truly

monstrous marginalia grotesques, prepared by anonymous illuminators. Indeed, in

her fascinating book Monsters and Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts

(2002), Alixe Bovey, a curator in the British Library's Department of

Manuscripts, notes that the realistic scenes of daily life on a medieval estate

such as owned by the Luttrells as portrayed in this psalter are interspersed

with:

…creatures of such startling monstrosity

that they prompted one scholar to comment that 'the mind of a man who could

deliberately set himself to ornament a book with such subjects…can hardly have

been normal'. While it seems unwise to use the margins of the Luttrell Psalter

to diagnose the mental condition of its artists, there can be no doubt that the

artist who illuminated many of its pages had an exceptionally fertile

imagination.

Indeed he did, and as proof of that, here is a

noteworthy avian malacomorph that appears on f 171v of the Luttrell Psalter:

The Hours of Joanna the Mad

is an illuminated book of hours manuscript that had originally been owned by

Joanna of Castile (1479-1555), the (controversially) mentally-ill consort of

Philip the Handsome, king of Castile. It had been produced for her in the

city of Bruges (in what is now Belgium) some time between 1486 and 1506, but

is now held as Add. MS 18852 in the British Library.

As with so many others of its kind, this illuminated manuscript's margins are

plentifully supplied with grotesques and drolleries, including a couple of very

distinctive malacomorphs – one of which is a bearded snail-man, the other a snail-stag.

A mirror-image pair of snail-stags

from f 305r and f 305v (hence they do not face each other, but I've realigned

them to do so here) in the Hours of Joanna the Mad (public

domain)

An antiphonary is one of the liturgical books

intended for use in the liturgical choir, and many medieval examples were

elaborately illuminated. One of these is the multi-volume antiphony produced

during the 1400s for the Augustinian monastery of San Gaggio (i.e. Pope St

Caius) in Florence, Italy, and among its numerous marginalia is a collared

snail-dog, with horns or horn-like ears:

The Tours MS 0008 manuscript held by the

Bibliothèque Municipale in Tours, France, dates from c.1320, originated in Spain, and consists of an illuminated Bible with Latin

text, which contains a veritable pantheon of marginalia, including two

appearances by snail-goats. In one of these appearances, the horned,

beardy-chinned malacomorph in question is defiantly sticking its tongue out at

a knight about to shoot it with an arrow (on f 89r); and in the other (on f

327v), it is using its tongue to do something unmentionable to a certain part

of a nearby monkey's anatomy!

The Breviary of Renaud de Bar is MS 107 in the collections of the Bibliothèque Municipale in Verdun, France. Dating from the early 1300s, it was commissioned

for Renaud de Bar, the bishop of Metz, by his sister, Marguerite, who was the abbess of

Abby St Maur. On f 97r is a snail-monk holding a forked club; similarly, on f

107 v, a snail-woman is wielding a forked club and also holding a shield as she

confronts a girl wearing nothing but a cap and a mantle that she is holding

open towards the malacomorph like some medieval flasher! And on f 160v, yet

another forked club is being parried, this time by a man with a shield opposing

a rearing snail-goat with long curved horns.

The Varie Hours is an exceedingly ornate illuminated

book of hours commissioned by 15th-Century French court official

Simon de Varie. Completed in 1455, it was subsequently divided into three

volumes; the first two are held at the National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague, the third at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, USA.

What is especially interesting in terms of its profuse array of marginalia is that this particular book of hours depicts malacomorphs of a fundamentally different nature from those hitherto observed by me in illuminated manuscripts. For instead of possessing spherical spiralled shells like typical land snails, they sport long, pointed spiralled shells similar to those of certain marine gastropods such as Turritella. Two of these atypical malacomorphs can be found on the same folio – f 72 in Vol. 3 – one of which is a snail-goat (at the bottom), and the other (at the top) a composite with the head of a bearded be-turbaned man but the furry upper torso and pawed forelegs of an undetermined animal.

What is especially interesting in terms of its profuse array of marginalia is that this particular book of hours depicts malacomorphs of a fundamentally different nature from those hitherto observed by me in illuminated manuscripts. For instead of possessing spherical spiralled shells like typical land snails, they sport long, pointed spiralled shells similar to those of certain marine gastropods such as Turritella. Two of these atypical malacomorphs can be found on the same folio – f 72 in Vol. 3 – one of which is a snail-goat (at the bottom), and the other (at the top) a composite with the head of a bearded be-turbaned man but the furry upper torso and pawed forelegs of an undetermined animal.

Two malacomorphs on f 72 in Vol. 3 of the Varie Hours (public

domain/courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum)

In view of its famous slowness of pace, in

Christian symbolism the snail came to epitomise the deadly sin of sloth and

laziness. And the cat fared little better in such symbolism, traditionally

deemed to personify lasciviousness and cruelty, and to be in league with the

forces of darkness. Consequently, it does not bode well for a snail-cat present

in a Christian illuminated manuscript to symbolise anything positive or

benevolent.

Having said that, however, there is no indication

that these feline malacomorphs were intended to signify anything at all. This

is because their appearances as marginalia in various folios from such

manuscripts seem not to correspond in any way with the main content or text of

those particular folios. The same is also true not only for other malacomorphs

but also for many marginalia grotesques and drolleries in general.

If anything, their presence often tends to be more

subversive than pertinent, i.e. suggesting that the illuminators have inserted

them as sly or playful attempts to mock, deflate, or even act as light, comic

relief to the strictly serious, devotional nature of the folios' principal

content rather than to instruct or act in any kind of directly relevant,

contextual manner.

Moreover, in some cases this phantasmagorical

menagerie of marginalia might be nothing more significant than the product of

illuminators' attempts to stave off boredom when faced with the exceedingly

long and very tedious task of copying or illuminating a major manuscript.

In short, snail-cats and various other bizarre

fauna of the folios may simply be medieval doodles, originally executed

centuries ago merely as brief, functionless escapes from ennui, but cherished

today in their own right as fascinating, captivating fantasies that add charm,

surprise, and not a little rebellion to the sternly religious literary abodes

in which they linger and lurk, always ready to startle unwary readers with

their extraordinary forms and outrageous, humorous behaviour – and long may

they continue to do so!

this made me get up out of my seat and start applauding

ReplyDelete