Following on from my two most recent ShukerNature blog posts (click here and here to view them), here is a third one that once again links a couple of my greatest interests – natural history and philately.

Thanks to my trio of definitive books documenting them (The Lost Ark, 1993; The New Zoo, 2002; and The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals, 2012), I am more readily associated with zoological arrivals and revivals than I am with extinct and endangered species.

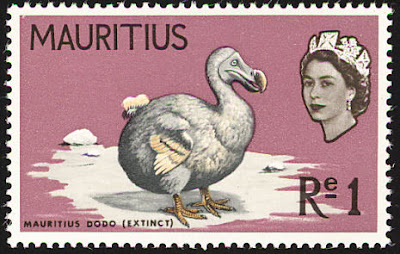

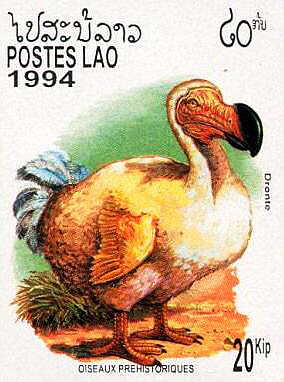

So now, by way of contrast and compensation, this present ShukerNature blog post surveys a varied selection of the most famous and extraordinary residents of Nature’s missing menagerie of vanished creatures. Although they are represented nowadays only by lifeless museum specimens and a few faded photographs, their original beauty and grandeur is recaptured for all time in numerous modern-day works of art – including, as selected from my own personal collection of wildlife-themed postage stamps and presented here, an eyecatching gallery of the philatelic variety.

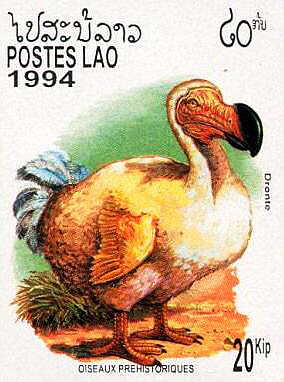

AS DEAD AS THE DODO

By popular zoological convention, an animal is said to have become extinct in historical times if it died out after 1681 AD. However, this is not an arbitrary date. On the contrary, 1681 is the official year of demise for the most famous modern-day extinct species of all – the dodo Raphus cucullatus of Mauritius. ‘As dead as the dodo’ is a popular contemporary expression of extinction or general obsolescence, but the dodo was once very much alive. This giant hook-beaked relative of doves and pigeons had survived untroubled by other species for countless ages on its island home in the Indian Ocean, and, as a result of having no need to flee from anything, had gradually lost the power of flight, becoming ever larger until it was the size of a turkey.

Size, however, was not the only characteristic that the dodo shared with the turkey. Like the latter bird, it was not overly encumbered with brainpower, and its flesh, though not tasty, was at least palatable. These two attributes would spell its inevitable doom if ever it were to encounter humankind – and finally, after Mauritius had enjoyed centuries of secure isolation, this is precisely what happened.

During the early 16th Century, Portuguese sailors began visiting the island, using it as a stop-over location for supplying their ships with food during long oceanic voyages. The dodo, trusting and edible, was a prime target. Later, the Portugese were replaced by the Dutch, who in 1644 established Mauritius as a Dutch colony. By now, the slaughter of dodos had become almost a sport in terms of popularity among the colonists, and its inevitable demise was hastened by persecution from various non-native species introduced here by humans, most notably the rat, dog, cat, monkey, and pig.

By the end of the 17th Century, less than 200 years since the island’s first visitation by Europeans, Mauritius had lost its most iconic inhabitant (and several of its other exotic endemic birds would also be exterminated in the years that followed). The dodo was no more, and the age of modern-day extinction had begun.

THE PASSING OF THE PASSENGER PIGEON

During the next three centuries, a host of other pigeons, doves, and even a swan-sized dodo relative called the Rodrigues solitaire would be wiped out in remote localities all over the world, but no such extinction would be more surprising – indeed, scarcely believable - than that of the passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius. Not only was this handsome species native to the North American continent (as opposed to some far-flung tropical isle only lately reached for the first time by humankind), but it was once incomprehensibly numerous. In fact, as recently as the 19th Century it was deemed to be the most abundant bird that had ever existed anywhere on the planet – its single species accounting for almost 40% of North America’s entire bird population. The following incident demonstrates this well.

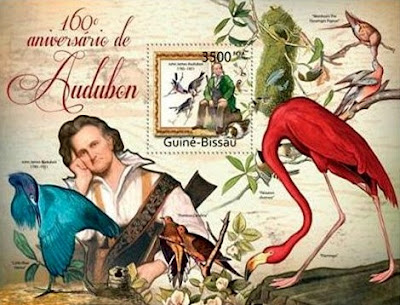

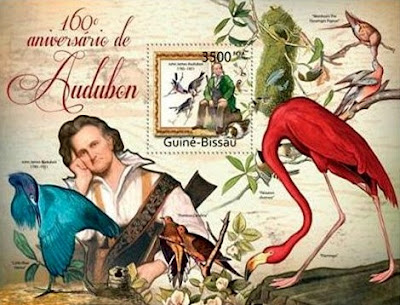

One autumn day in 1813, while travelling on a wagon from his Ohio River home to Louisville, Kentucky, around 88 km away, the great American bird painter John James Audubon (who famously painted this now-lost species) witnessed a stupendous flock of passenger pigeons flying overhead in a colossal mass, which so filled the sky above that in his own words: “[the] light of noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse”. So immense was the flock that when he arrived at Louisville at sunset, it was still passing overhead - an unbroken, seemingly never-ending cloud of life that according to conservative estimates must have contained well over one billion pigeons!

It will come as no surprise, sadly, to learn that the sight of such unimaginable numbers triggered in every sense an insatiable bloodlust among the sporting fraternity of America, and hunters would shoot endlessly at these massive migrations of pigeons, a single bullet often bringing down multiple birds. On and on the slaughter continued, year after year, decade after decade (around a billion pigeons were killed during a single hunt held in 1878 close to Petoskey, Michigan), as it seemed impossible even to contemplate that any depredation, however sustained, would affect the numbers of this innumerable bird – but it did.

Astonishingly, by the end of the 19th Century, the most abundant bird that had ever been had become, in relative terms, a rarity, but even worse was to follow. Less than a quarter of a million pigeons remained, all contained within a single great nesting flock in Ohio - which was almost totally destroyed when a massive hunting party descended upon it, leaving no more than 5000 birds alive.

Too late it was realised that this uniquely prolific species needed enormous numbers for successful reproduction. The sparse quantity that now remained was insufficient, and so the passenger pigeon plummeted headlong into the abyss of extinction. The last known wild specimen was shot in Ohio in 1900, and on 1 September 1914, at the grand old age of 29, the last passenger pigeon in the world, a lone female called Martha Washington, died in her cage at Cincinnati Zoo, and in so doing marked the death of an entire species – one that had once seemed indestructible. The unthinkable had happened – the passenger pigeon was extinct.

Incredibly, only four years after Martha’s death, a second very significant North American species also met its untimely end in the very same zoo, when in 1918 the world’s last Carolina parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis died here. Although nowhere near as numerous as the passenger pigeon, this highly attractive yellow-headed, green-bodied species – the U.S.A.’s only native species of parrot – had once been a common sight through much of the continent’s eastern and southern regions, but it was irresistibly attracted to the fruit of farmers’ orchards and the grain of their fields, and so, like the pigeon, it was doomed.

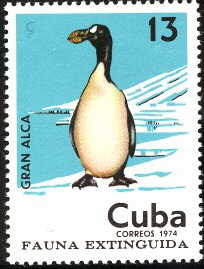

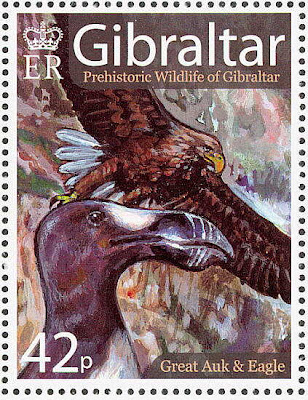

RAIDERS OF THE LOST AUK

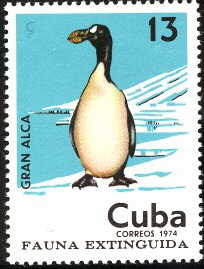

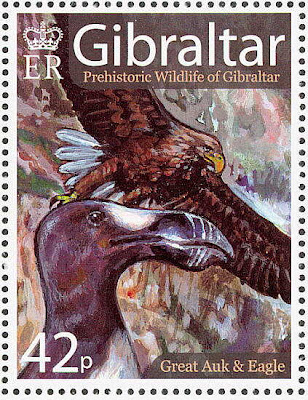

Another famous vanished species is the great auk Pinguinus impennis. This large flightless black-and-white seabird from the northern hemisphere was superficially reminiscent of the southern hemisphere’s familiar penguins, but its link with them does not end there – because the great auk was the original penguin, the latter name having been initially bestowed upon this puffin-allied species. Only later was it applied by those European sailors first penetrating Antarctic waters to the wholly-unrelated birds that they encountered there and which retain it today, long after the original penguin’s extermination.

The great auk once existed in tens of millions, nesting on the rocky coastal areas of islands on both sides of the North Atlantic, but it was in America that it first met its end. Its feathers were prized for use in eider-downs and feather beds, its flesh was tasty and therefore much sought-after by sailing vessels, and collectors coveted its eggs, and so this imposing but helpless bird was massacred in countless numbers. On Funk Island off Newfoundland, for example, its precious nesting grounds were frequently raided and mercilessly desecrated. Thousands of auks were captured alive and cooped together in great enclosures like domestic fowl until it was their time to be slaughtered en masse by being clubbed to death and then thrown into furnaces, enabling their feathers to be more readily removed from their bodies. By the second decade of the 19th Century, the great auk was merely a memory in North America.

In Europe, its major stronghold was the Icelandic coast, but great auks even existed around the more northerly islands of Scotland, most notably St Kilda but also visiting the Orkneys, with one particularly famous Orcadian pair being nicknamed the King and Queen. Sadly, however, they were no safer from hunting here than they had been in the New World. Moreover, it was especially ironic that as this species became rarer, it became ever more persecuted by museum collectors - anxious to add specimens and eggs to their collections before it died out! The last known great auks constituted a pair clubbed to death (and their egg smashed) on the Icelandic island of Eldey on 3 June 1844.

For a few decades thereafter, some quite convincing reports of lone living specimens emerged from various remote far-northern European localities, but none was confirmed. Reports emanating from Norway’s Lofoten Islands during the 1920s and 1930s were duly investigated, only to discover that the birds in question were actually released Antarctic penguins. And a supposed great auk spied in the Orkneys during the 1980s that attracted considerable media attention owed more to a clever publicity campaign for a certain brand of whisky than it did to any unexpected resurrection of the lost auk.

ONE BIRD, TWO BEAKS

The great auk was not the only species hastened into extinction by the mercenary actions of museum curators. Moving from the North Atlantic to the North Island, of New Zealand, the huia Heteralocha acutirostris was a large predominantly black-plumaged bird whose long broad tail’s tip bore a striking white horizontal band, and its cheeks sported a pair of bright orange wattles. Indeed, it was a member of a small family of birds known as wattlebirds, found only in New Zealand.

What singled the huia out from all other birds, however, was its beak – or, rather, its beaks. Uniquely, the beak of the male huia was totally different in shape from that of the female huia - the former’s was short and straight, the latter’s was long and downward-curving. A pair would work together when seeking the wood-inhabiting grubs on which they fed – the male using his hard, sharp beak to chisel through rotting bark in search of the grubs, and the female then hooking them out with her more delicate, curved beak.

Tragically, however, this unparalleled avian teamwork would soon come to an end – when the species itself died out. Traditionally, the huia’s eyecatching tail feathers had been used in ceremonial Maori head-dresses, but when Europeans arrived their usual unwelcome contingent of rats and cats lost no time in decimating the endemic bird population of New Zealand, and the huia proved to be particularly vulnerable not just to predation by these and other alien species but also to various diseases associated with them. And as with the great auk, once the huia’s numbers crashed, museum curators who realised that they held few specimens of this extraordinary species soon made known their requirement for more, thereby sounding the death knell for this highly endangered bird.

The last known huia was sighted in 1907, and although, as documented in my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007), a few unconfirmed sightings have been made since, including one by Danish zoologist Lars Thomas as recently as 1991, until further notice the huia remains yet another tragic inhabitant of the missing menagerie.

THE SORRY SAGA OF A SEA COW

Birds are not the only species to have lost some of their most dramatic members either. Three of the most spectacular mammals to have disappeared since the dodo are Steller’s sea cow Hydrodamalis (=Rhytina) gigas, the quagga Equus burchelli quagga, and the thylacine (Tasmanian wolf) Thylacinus cynocephalus.

Scientifically discovered in 1741 by Russian naturalist Georg Steller, during the Bering Expedition to the icy waters of far-eastern Russia’s North Pacific, and duly named after him, Steller’s sea cow measured approximately 8 m long. This made it by far the largest member of the taxonomic order of mammals known as sirenians, named after the fondly-held belief that sightings by sailors of some of the smaller species, known as manatees and dugongs, had inspired the belief in mermaids or sirens.

When his ship was wrecked on the coast of one of the Bering Sea’s previously-uncharted Commander Islands, Steller had plenty of time to observe in detail these enormous but wholly inoffensive, herbivorous mammals that grazed upon seaweed and gave voice to loud, lugubrious groans. Among the countless discoveries that he made about them was that their flesh was delicious – a fact not lost upon the various expeditions that arrived here in the years to come. So much so, in fact, that by 1768, a mere 27 years after the first one had been seen by Steller, the last of his eponymous sea cows was killed, and the mournful song of this strange mega-mermaid was forever stilled.

THE ZEBRA THAT LOST ITS STRIPES…AND ITS SURVIVAL

Named after the sound of its strange high-pitched whinny, the quagga of South Africa could more aptly be termed a quasi-zebra, for unlike the uniformly striped zebras familiar to one and all today, the quagga, uniquely, was striped only on its face, neck, and anterior forequarters – its flanks and hindquarters were wholly brown and unstriped, and its legs were predominantly white. Although still present in huge herds as late as the 1840s, during the next three decades the quagga was hunted in great numbers by the Boers for its hide and its meat. Its decimation in the wild was completed with the killing of the last known wild specimen in 1878. On account of its unusual appearance, a number of quaggas had been exhibited at various zoos, but in those pre-conservation days no attempt was made to breed this very interesting creature, so when the last captive specimen died at Amsterdam Zoo in 1883, the quagga was gone forever – or was it?

A fascinating captive breeding programme, the Quagga Project, pioneered by natural historian Reinhold Rau, has been underway since the 1990s in South Africa, attempting to recreate the quagga by selective breeding, using specimens of the plains zebra Equus burchelli (of which the quagga was a subspecies) with fewer stripes than normal. Some decidedly quagga-like individuals have already been engendered, but whether they share the original quagga’s genetic make-up rather than merely its outward form has yet to be determined.

THE ONCE AND FUTURE THYLACINE?

Another lost creature that may yet rise again like a veritable phoenix in stripes was – or is, or will be again? – the thylacine or Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus (popularly translated as ‘pouched dog with wolf’s head’, on account of its decidedly canine head and offspring-rearing pouch). Remarkably lupine in superficial external appearance (but wholly unrelated to real wolves and dogs), it was also known as the Tasmanian tiger due to its series of distinctive body and tail stripes. This very impressive creature was the world’s largest carnivorous marsupial (pouched mammal), and although confined in historical times to the island of Tasmania, only a couple of millennia ago it also thrived in mainland Australia, and formerly in New Guinea as well.

Yet despite its spectacular appearance, the thylacine won no fans among European settlers on Tasmania, especially those with farm livestock, whose lambs and sheep proved particularly tempting to this meat-eating mammal – although to be fair, more sheep were killed by introduced domestic dogs there than were ever killed by this island’s pouched counterparts. Nevertheless, in 1888, the Tasmanian government offered a bounty for every thylacine shot, and so, as had happened to all too many other species at other times elsewhere, the annihilation duly began. In 1936, when realisation of the fate awaiting what by now had been scientifically recognised as a priceless product of Antipodean evolution belatedly hit the Tasmanian government, it finally granted the thylacine full protection. The timing was impeccable – impeccably bad, that is, bearing in mind that the world’s last thylacine, a female specimen known somewhat oddly as Benjamin, died at Hobart Zoo just two months later; the last confirmed wild specimen had been shot in 1930.

Having said that, the thylacine has since earned itself the title of the world’s most common extinct animal, because seldom has a year gone by ever since without alleged sightings of specimens emerging from one region or another of Tasmania, and sometimes by very experienced, reliable eyewitnesses such as national park wardens. Consequently, some zoologists remain reluctant to deny categorically that the thylacine still survives, but without any physical, unequivocal evidence to hand, the case for its survival remains unresolved.

Like the quagga, however, plans are afoot to resurrect this fairly recently-extirpated enigma, but this time by means of cloning DNA extracted from various well-preserved museum specimens. Some Australian scientists are confident that the technology to accomplish this Jurassic Park scenario may soon be forthcoming, and that before much longer a living breathing thylacine will once more be a reality.

AND NOT FORGETTING…

Meanwhile, the extinct species described in this article are just a handful of the hundreds of truly exceptional creatures that have been wiped out since the dodo. Others include the colossal ostrich-like elephant bird of Madagascar Aepyornis maximus (end of the 18th Century), South Africa’s blaauwbok Hippotragus leucophaeus (1799; Africa's first large mammal to become extinct in historical times); the Labrador (pied) duck Camptorhynchus labradorius (1875; black-and-white North American waterfowl only distantly allied to other ducks); and the Falkland Islands fox Dusicyon australis (1876; wholly confined to this South Atlantic island group).

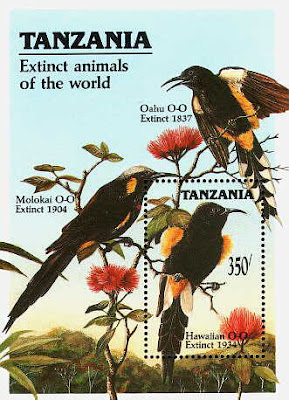

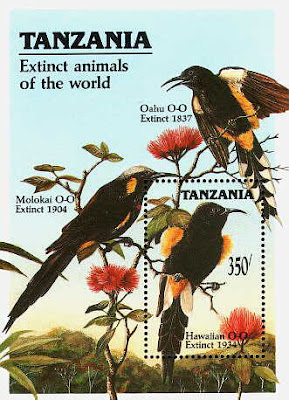

Over a dozen species of finch-related Hawaiian honeycreepers have become extinct in modern times too (including in 1898 the gorgeously-plumed mamo Drepanis pacifica), plus at least three different species of exotic black-and-yellow o-o birds (also Hawaiian, and named after their distinctive call).

Also extinct is the toolach Macropus greyi (1939; an exceptionally beautiful wallaby); the Caribbean monk seal Monachus tropicalis (1952; a specimen was once owned by Fidel Castro); and the all-white Chinese river dolphin or baiji Lipotes vexillifer (declared extinct in 2004, after having first been made known to western science as recently as 1918). And these are just a few from the disturbingly long list of species that have vanished since the dodo's own disappearance just over three centuries ago.

The cloning of a thylacine, or any other of the presently lost species documented here, would certainly be a marvel, but just because extinction might indeed become reversible in the up-and-coming future, we must never forget what destruction our ancestors have wrought upon the living world in the not-so-distant past, and we must ensure that such activity is never repeated anywhere in the present. Who knows – perhaps in the not-too-distant future extinction may no longer be forever, but it should never be at all.

Thanks to my trio of definitive books documenting them (The Lost Ark, 1993; The New Zoo, 2002; and The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals, 2012), I am more readily associated with zoological arrivals and revivals than I am with extinct and endangered species.

So now, by way of contrast and compensation, this present ShukerNature blog post surveys a varied selection of the most famous and extraordinary residents of Nature’s missing menagerie of vanished creatures. Although they are represented nowadays only by lifeless museum specimens and a few faded photographs, their original beauty and grandeur is recaptured for all time in numerous modern-day works of art – including, as selected from my own personal collection of wildlife-themed postage stamps and presented here, an eyecatching gallery of the philatelic variety.

AS DEAD AS THE DODO

By popular zoological convention, an animal is said to have become extinct in historical times if it died out after 1681 AD. However, this is not an arbitrary date. On the contrary, 1681 is the official year of demise for the most famous modern-day extinct species of all – the dodo Raphus cucullatus of Mauritius. ‘As dead as the dodo’ is a popular contemporary expression of extinction or general obsolescence, but the dodo was once very much alive. This giant hook-beaked relative of doves and pigeons had survived untroubled by other species for countless ages on its island home in the Indian Ocean, and, as a result of having no need to flee from anything, had gradually lost the power of flight, becoming ever larger until it was the size of a turkey.

Size, however, was not the only characteristic that the dodo shared with the turkey. Like the latter bird, it was not overly encumbered with brainpower, and its flesh, though not tasty, was at least palatable. These two attributes would spell its inevitable doom if ever it were to encounter humankind – and finally, after Mauritius had enjoyed centuries of secure isolation, this is precisely what happened.

During the early 16th Century, Portuguese sailors began visiting the island, using it as a stop-over location for supplying their ships with food during long oceanic voyages. The dodo, trusting and edible, was a prime target. Later, the Portugese were replaced by the Dutch, who in 1644 established Mauritius as a Dutch colony. By now, the slaughter of dodos had become almost a sport in terms of popularity among the colonists, and its inevitable demise was hastened by persecution from various non-native species introduced here by humans, most notably the rat, dog, cat, monkey, and pig.

By the end of the 17th Century, less than 200 years since the island’s first visitation by Europeans, Mauritius had lost its most iconic inhabitant (and several of its other exotic endemic birds would also be exterminated in the years that followed). The dodo was no more, and the age of modern-day extinction had begun.

THE PASSING OF THE PASSENGER PIGEON

During the next three centuries, a host of other pigeons, doves, and even a swan-sized dodo relative called the Rodrigues solitaire would be wiped out in remote localities all over the world, but no such extinction would be more surprising – indeed, scarcely believable - than that of the passenger pigeon Ectopistes migratorius. Not only was this handsome species native to the North American continent (as opposed to some far-flung tropical isle only lately reached for the first time by humankind), but it was once incomprehensibly numerous. In fact, as recently as the 19th Century it was deemed to be the most abundant bird that had ever existed anywhere on the planet – its single species accounting for almost 40% of North America’s entire bird population. The following incident demonstrates this well.

One autumn day in 1813, while travelling on a wagon from his Ohio River home to Louisville, Kentucky, around 88 km away, the great American bird painter John James Audubon (who famously painted this now-lost species) witnessed a stupendous flock of passenger pigeons flying overhead in a colossal mass, which so filled the sky above that in his own words: “[the] light of noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse”. So immense was the flock that when he arrived at Louisville at sunset, it was still passing overhead - an unbroken, seemingly never-ending cloud of life that according to conservative estimates must have contained well over one billion pigeons!

It will come as no surprise, sadly, to learn that the sight of such unimaginable numbers triggered in every sense an insatiable bloodlust among the sporting fraternity of America, and hunters would shoot endlessly at these massive migrations of pigeons, a single bullet often bringing down multiple birds. On and on the slaughter continued, year after year, decade after decade (around a billion pigeons were killed during a single hunt held in 1878 close to Petoskey, Michigan), as it seemed impossible even to contemplate that any depredation, however sustained, would affect the numbers of this innumerable bird – but it did.

Astonishingly, by the end of the 19th Century, the most abundant bird that had ever been had become, in relative terms, a rarity, but even worse was to follow. Less than a quarter of a million pigeons remained, all contained within a single great nesting flock in Ohio - which was almost totally destroyed when a massive hunting party descended upon it, leaving no more than 5000 birds alive.

Too late it was realised that this uniquely prolific species needed enormous numbers for successful reproduction. The sparse quantity that now remained was insufficient, and so the passenger pigeon plummeted headlong into the abyss of extinction. The last known wild specimen was shot in Ohio in 1900, and on 1 September 1914, at the grand old age of 29, the last passenger pigeon in the world, a lone female called Martha Washington, died in her cage at Cincinnati Zoo, and in so doing marked the death of an entire species – one that had once seemed indestructible. The unthinkable had happened – the passenger pigeon was extinct.

Incredibly, only four years after Martha’s death, a second very significant North American species also met its untimely end in the very same zoo, when in 1918 the world’s last Carolina parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis died here. Although nowhere near as numerous as the passenger pigeon, this highly attractive yellow-headed, green-bodied species – the U.S.A.’s only native species of parrot – had once been a common sight through much of the continent’s eastern and southern regions, but it was irresistibly attracted to the fruit of farmers’ orchards and the grain of their fields, and so, like the pigeon, it was doomed.

RAIDERS OF THE LOST AUK

Another famous vanished species is the great auk Pinguinus impennis. This large flightless black-and-white seabird from the northern hemisphere was superficially reminiscent of the southern hemisphere’s familiar penguins, but its link with them does not end there – because the great auk was the original penguin, the latter name having been initially bestowed upon this puffin-allied species. Only later was it applied by those European sailors first penetrating Antarctic waters to the wholly-unrelated birds that they encountered there and which retain it today, long after the original penguin’s extermination.

The great auk once existed in tens of millions, nesting on the rocky coastal areas of islands on both sides of the North Atlantic, but it was in America that it first met its end. Its feathers were prized for use in eider-downs and feather beds, its flesh was tasty and therefore much sought-after by sailing vessels, and collectors coveted its eggs, and so this imposing but helpless bird was massacred in countless numbers. On Funk Island off Newfoundland, for example, its precious nesting grounds were frequently raided and mercilessly desecrated. Thousands of auks were captured alive and cooped together in great enclosures like domestic fowl until it was their time to be slaughtered en masse by being clubbed to death and then thrown into furnaces, enabling their feathers to be more readily removed from their bodies. By the second decade of the 19th Century, the great auk was merely a memory in North America.

In Europe, its major stronghold was the Icelandic coast, but great auks even existed around the more northerly islands of Scotland, most notably St Kilda but also visiting the Orkneys, with one particularly famous Orcadian pair being nicknamed the King and Queen. Sadly, however, they were no safer from hunting here than they had been in the New World. Moreover, it was especially ironic that as this species became rarer, it became ever more persecuted by museum collectors - anxious to add specimens and eggs to their collections before it died out! The last known great auks constituted a pair clubbed to death (and their egg smashed) on the Icelandic island of Eldey on 3 June 1844.

For a few decades thereafter, some quite convincing reports of lone living specimens emerged from various remote far-northern European localities, but none was confirmed. Reports emanating from Norway’s Lofoten Islands during the 1920s and 1930s were duly investigated, only to discover that the birds in question were actually released Antarctic penguins. And a supposed great auk spied in the Orkneys during the 1980s that attracted considerable media attention owed more to a clever publicity campaign for a certain brand of whisky than it did to any unexpected resurrection of the lost auk.

ONE BIRD, TWO BEAKS

The great auk was not the only species hastened into extinction by the mercenary actions of museum curators. Moving from the North Atlantic to the North Island, of New Zealand, the huia Heteralocha acutirostris was a large predominantly black-plumaged bird whose long broad tail’s tip bore a striking white horizontal band, and its cheeks sported a pair of bright orange wattles. Indeed, it was a member of a small family of birds known as wattlebirds, found only in New Zealand.

What singled the huia out from all other birds, however, was its beak – or, rather, its beaks. Uniquely, the beak of the male huia was totally different in shape from that of the female huia - the former’s was short and straight, the latter’s was long and downward-curving. A pair would work together when seeking the wood-inhabiting grubs on which they fed – the male using his hard, sharp beak to chisel through rotting bark in search of the grubs, and the female then hooking them out with her more delicate, curved beak.

Tragically, however, this unparalleled avian teamwork would soon come to an end – when the species itself died out. Traditionally, the huia’s eyecatching tail feathers had been used in ceremonial Maori head-dresses, but when Europeans arrived their usual unwelcome contingent of rats and cats lost no time in decimating the endemic bird population of New Zealand, and the huia proved to be particularly vulnerable not just to predation by these and other alien species but also to various diseases associated with them. And as with the great auk, once the huia’s numbers crashed, museum curators who realised that they held few specimens of this extraordinary species soon made known their requirement for more, thereby sounding the death knell for this highly endangered bird.

The last known huia was sighted in 1907, and although, as documented in my book Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007), a few unconfirmed sightings have been made since, including one by Danish zoologist Lars Thomas as recently as 1991, until further notice the huia remains yet another tragic inhabitant of the missing menagerie.

THE SORRY SAGA OF A SEA COW

Birds are not the only species to have lost some of their most dramatic members either. Three of the most spectacular mammals to have disappeared since the dodo are Steller’s sea cow Hydrodamalis (=Rhytina) gigas, the quagga Equus burchelli quagga, and the thylacine (Tasmanian wolf) Thylacinus cynocephalus.

Scientifically discovered in 1741 by Russian naturalist Georg Steller, during the Bering Expedition to the icy waters of far-eastern Russia’s North Pacific, and duly named after him, Steller’s sea cow measured approximately 8 m long. This made it by far the largest member of the taxonomic order of mammals known as sirenians, named after the fondly-held belief that sightings by sailors of some of the smaller species, known as manatees and dugongs, had inspired the belief in mermaids or sirens.

When his ship was wrecked on the coast of one of the Bering Sea’s previously-uncharted Commander Islands, Steller had plenty of time to observe in detail these enormous but wholly inoffensive, herbivorous mammals that grazed upon seaweed and gave voice to loud, lugubrious groans. Among the countless discoveries that he made about them was that their flesh was delicious – a fact not lost upon the various expeditions that arrived here in the years to come. So much so, in fact, that by 1768, a mere 27 years after the first one had been seen by Steller, the last of his eponymous sea cows was killed, and the mournful song of this strange mega-mermaid was forever stilled.

THE ZEBRA THAT LOST ITS STRIPES…AND ITS SURVIVAL

Named after the sound of its strange high-pitched whinny, the quagga of South Africa could more aptly be termed a quasi-zebra, for unlike the uniformly striped zebras familiar to one and all today, the quagga, uniquely, was striped only on its face, neck, and anterior forequarters – its flanks and hindquarters were wholly brown and unstriped, and its legs were predominantly white. Although still present in huge herds as late as the 1840s, during the next three decades the quagga was hunted in great numbers by the Boers for its hide and its meat. Its decimation in the wild was completed with the killing of the last known wild specimen in 1878. On account of its unusual appearance, a number of quaggas had been exhibited at various zoos, but in those pre-conservation days no attempt was made to breed this very interesting creature, so when the last captive specimen died at Amsterdam Zoo in 1883, the quagga was gone forever – or was it?

A fascinating captive breeding programme, the Quagga Project, pioneered by natural historian Reinhold Rau, has been underway since the 1990s in South Africa, attempting to recreate the quagga by selective breeding, using specimens of the plains zebra Equus burchelli (of which the quagga was a subspecies) with fewer stripes than normal. Some decidedly quagga-like individuals have already been engendered, but whether they share the original quagga’s genetic make-up rather than merely its outward form has yet to be determined.

THE ONCE AND FUTURE THYLACINE?

Another lost creature that may yet rise again like a veritable phoenix in stripes was – or is, or will be again? – the thylacine or Tasmanian wolf Thylacinus cynocephalus (popularly translated as ‘pouched dog with wolf’s head’, on account of its decidedly canine head and offspring-rearing pouch). Remarkably lupine in superficial external appearance (but wholly unrelated to real wolves and dogs), it was also known as the Tasmanian tiger due to its series of distinctive body and tail stripes. This very impressive creature was the world’s largest carnivorous marsupial (pouched mammal), and although confined in historical times to the island of Tasmania, only a couple of millennia ago it also thrived in mainland Australia, and formerly in New Guinea as well.

Yet despite its spectacular appearance, the thylacine won no fans among European settlers on Tasmania, especially those with farm livestock, whose lambs and sheep proved particularly tempting to this meat-eating mammal – although to be fair, more sheep were killed by introduced domestic dogs there than were ever killed by this island’s pouched counterparts. Nevertheless, in 1888, the Tasmanian government offered a bounty for every thylacine shot, and so, as had happened to all too many other species at other times elsewhere, the annihilation duly began. In 1936, when realisation of the fate awaiting what by now had been scientifically recognised as a priceless product of Antipodean evolution belatedly hit the Tasmanian government, it finally granted the thylacine full protection. The timing was impeccable – impeccably bad, that is, bearing in mind that the world’s last thylacine, a female specimen known somewhat oddly as Benjamin, died at Hobart Zoo just two months later; the last confirmed wild specimen had been shot in 1930.

Having said that, the thylacine has since earned itself the title of the world’s most common extinct animal, because seldom has a year gone by ever since without alleged sightings of specimens emerging from one region or another of Tasmania, and sometimes by very experienced, reliable eyewitnesses such as national park wardens. Consequently, some zoologists remain reluctant to deny categorically that the thylacine still survives, but without any physical, unequivocal evidence to hand, the case for its survival remains unresolved.

Like the quagga, however, plans are afoot to resurrect this fairly recently-extirpated enigma, but this time by means of cloning DNA extracted from various well-preserved museum specimens. Some Australian scientists are confident that the technology to accomplish this Jurassic Park scenario may soon be forthcoming, and that before much longer a living breathing thylacine will once more be a reality.

AND NOT FORGETTING…

Meanwhile, the extinct species described in this article are just a handful of the hundreds of truly exceptional creatures that have been wiped out since the dodo. Others include the colossal ostrich-like elephant bird of Madagascar Aepyornis maximus (end of the 18th Century), South Africa’s blaauwbok Hippotragus leucophaeus (1799; Africa's first large mammal to become extinct in historical times); the Labrador (pied) duck Camptorhynchus labradorius (1875; black-and-white North American waterfowl only distantly allied to other ducks); and the Falkland Islands fox Dusicyon australis (1876; wholly confined to this South Atlantic island group).

Over a dozen species of finch-related Hawaiian honeycreepers have become extinct in modern times too (including in 1898 the gorgeously-plumed mamo Drepanis pacifica), plus at least three different species of exotic black-and-yellow o-o birds (also Hawaiian, and named after their distinctive call).

Also extinct is the toolach Macropus greyi (1939; an exceptionally beautiful wallaby); the Caribbean monk seal Monachus tropicalis (1952; a specimen was once owned by Fidel Castro); and the all-white Chinese river dolphin or baiji Lipotes vexillifer (declared extinct in 2004, after having first been made known to western science as recently as 1918). And these are just a few from the disturbingly long list of species that have vanished since the dodo's own disappearance just over three centuries ago.

The cloning of a thylacine, or any other of the presently lost species documented here, would certainly be a marvel, but just because extinction might indeed become reversible in the up-and-coming future, we must never forget what destruction our ancestors have wrought upon the living world in the not-so-distant past, and we must ensure that such activity is never repeated anywhere in the present. Who knows – perhaps in the not-too-distant future extinction may no longer be forever, but it should never be at all.

I don't think there is anything more to add. You have summed it up beautifully: extinction is a curse. We will not live in peace until this madness ends.

ReplyDeleteAll the best, The Thinker

Call me crazy, but I just don't accept (and never have accepted) the conventional explanation for the demise of the passenger pigeon. Yes, they were hunted, but so are our duck and geese populations, all of which are far smaller than the passenger pigeon numbers 150 years ago. We readily (if not happily) accept responsibility for killing all of the passenger pigeons, as proof of man's cruel nature. But beyond the moral lesson, how in the world was there enough ammunition to kill billions and billions of these birds! They weren't on a tiny island; they didn't have finicky eating habits. they were incredibly prolific. Seems like an abdication of the scientific method to just assume they're all gunshot (and netting) victims. Not saying aliens abducted them or they flew into the hollow earth, i just want a credible explanation. No one has ever supplied one. (Species specific virus? Interbreeding with other pigeons? Anything?)

ReplyDeleteHumans didn't shoot all of the passenger pigeons - lots, definitely, but not all of them. What happened, as noted above in my article, was that the enormous number of birds that were shot was enough to diminish the total population to the point where this species could no longer breed effectively. It was a species that seemingly needed to exist in vast numbers in order to breed effectively - in smaller numbers, this effectiveness was lost, and, with it, so was the entire species.

ReplyDeleteI understood that point in your article, but still find it difficult to understand why they needed such huge numbers to survive. Seems like an ex post facto explanation, given what we know of similar pigeon species which do just fine. Given the competition for food and nesting space, one would think excessive numbers (billions and billions in a flock) would be a drag, not a positive. Sorry, the "passenger pigeon, hunted to extinction" theme just sticks in my craw. :)

ReplyDeleteIn fact, the passenger pigeon was not alone in this requirement. Certain other species have similar requirements, most notably the Australian flock pigeon (hence its name), as well ascertain other birds such as the African finch-related queleas, which are probably now the world's most abundant wild bird species. And the very fact that there were indeed billions of passenger pigeons once, and had been since time immemorial until mankind invented firearms, shows that their vast numbers had not caused problems for them before.

ReplyDeleteOK, I understand. Further question though. How does the need for vast numbers in order to survive actually work? 3,000 passenger pigeons cannot survive, say, but 3,000,000,000 can? What good is conferred by the larger numbers?

ReplyDeleteOne last note. just saw this today; see several paragraphs down about scientists hoping to bring back the passenger pigeon. Presumably they'll realize they need to create huge flocks for continued viability. http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2013/02/28/marin-environmentalist-says-we-are-learning-to-reverse-extinction/

ReplyDeleteThe great numbers acted as a stimulus to reproduction - mass reproduction is a common phenomenon among animals. And yes, scientists may one day be able to clone the passenger pigeon, but there is more to resurrecting a species than the mechanics of doing so. It has to be ascertained that behaviourally and ecologically the species can survive in the modern world. For this reason, attempts to resurrect the woolly mammoth may not be successful, because even if the mechanics work, where, ecologically, would a woolly mammoth fit in, in today's post-Ice Age world?

ReplyDeleteYour Passenger Pigeon fancier here again. A new, longer article on the cloning efforts: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/03/passenger-pigeon-de-extinction/

ReplyDeleteAs you point out, the issue of a sustainable population needs to be addressed, as well as the effects on the world of unleashing what could again become vast flocks eating everything in their path and leaving dense mats of fecal matter!

My first thought on the need for massive numbers of the pigeons to suvive, is that 1) they have a high mortality rate among individuals that haven't reached breeding maturity, and two that even after that A LOT of animals probably snapped them up like popcorn as a side dish with their larger more sustaining meals.

ReplyDeleteSO between the possible mortality rate or eggs failing to hatch, as well as predation, even though their numbers were seemingly to huge to sustain itself it pobably did a fairly good job.

Also, the U.S. was no where near as developed then, and with the large amounts of grassy plains, bugs,fruit, seeds and nuts of all kinds growing wild, possibly even carrion since pigeons are known to eat meat scraps and such, there was probably plenty of food.