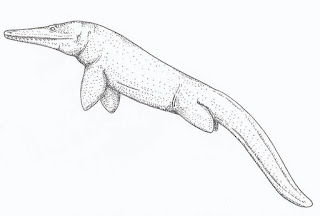

Artistic

reconstruction of Owen Burnham's discovery of the Gambian sea serpent carcase

(© William M. Rebsamen)

Doesn't time fly when you're having fun?! As I write this

introduction to the present ShukerNature blog article, I can scarcely believe

that over 30 years have gone by since I penned what became my very first

investigative cryptozoological article, published as a two-parter in the

September and October 1986 issues of a now long-defunct British magazine, The

Unknown. And what was my article's subject? Why, none other than a certain

mysterious sea beast found dead a few years earlier on a beach in The Gambia,

West Africa - the very same creature whose extraordinary history I am writing

about now. Clearly, time not only flies but also on occasion takes delight in

looping the loop!

Back in 1986, I became the first cryptozoologist to write about

the Gambian sea serpent, and went on to document it further in a number of

other publications, including various of my books, but most extensively of all

within my two works on putative prehistoric survivors – In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors (1995) and Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors

(2016). Indeed, it was this remarkable case that single-handedly (or even

single-flipperedly!) transformed me into a full-time independent researcher and

writer on the ever-fascinating subject of mystery beasts. Although I have since

investigated and duly introduced a very sizeable number of other hitherto

little-publicised or wholly-unpublicised cryptids to the general international

reading public, Gambo (as it was subsequently dubbed, although not by me – see later)

remains one of the most intriguing, tantalising, and controversial cryptids

that I have ever investigated.

My two books (not shown to scale) documenting putative prehistoric

survivors (© Dr Karl Shuker/Blandford Press / (© Dr Karl Shuker/Coachwhip

Publications)

Needless to say, therefore, it came as quite a shock when

recently I suddenly realised to my considerable embarrassment that apart from a

single exceedingly brief mention of its case in a Loch Ness monster article (click

here to read it), I had never documented

the Gambian sea serpent on ShukerNature. Consequently, in order to make very

belated amends for this major oversight on my part, I have great pleasure in

presenting herewith my complete coverage of this thoroughly captivating and

still-unresolved cryptid from my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors. Please welcome Gambo, the very mysterious

stranger on the shore that launched my cryptozoological career. I'm sure that

Mr Acker Bilk would have approved. (You need to be of a certain age and musical

persuasion to comprehend that comment!)

Incidentally, the coining of the name 'Gambo', by which the

Gambian sea serpent is nowadays very commonly referred to colloquially in

cryptozoological circles, is often mistakenly attributed to me, but here is the

true origin of this famous mystery beast moniker. It made its debut within the

title ('Gambo – The Beaked Beast of Bungalow Beach') of a three-page Fortean Times

article prepared in-house but credited to me as it constituted a condensed

version of my two-part article from 1986

in The Unknown, and was published in FT's

February/March 1993 issue (#67). Significantly, therefore, I did not directly

pen either the FT article itself (within whose second paragraph of main

text 'Gambo' was specifically introduced by whoever did pen it as the name by

which this cryptid would be referred to thereafter within the article) or its

title. Consequently, whoever the FT person was who did is also, therefore,

the person who coined the now-iconic name 'Gambo', and, in so doing, serendipitously

created a little snippet of cryptozoological history, but their identity has

never been disclosed (at least not to me, anyway!).

The Fortean Times article of February/March

1993 on the Gambian sea serpent, credited to me, and whose FT-penned

title constitutes the very first, now-historic appearance of the name 'Gambo' - please click to enlarge for reading purposes

(© Dr Karl Shuker/Fortean Times)

It all began on 12 June 1983, when wildlife enthusiast Owen Burnham and

three family members encountered the carcase of a huge sea creature, washed up

onto Bungalow Beach in The Gambia, West Africa. Most sea

monster remains are discovered in an advanced state of decomposition, greatly

distorting their appearance and making positive identification very difficult,

but the carcase found by Burnham was exceptional, as apparently it was largely

intact, with no external decomposition.

Subsequently

reallocating to England but having

lived most of his childhood and teenage years in Senegal, Owen was very

familiar with all of that region's major land and sea creatures, but he had

never seen anything like this before. Realising its potential zoological

significance, he made meticulous sketches and observations of its outward

morphology, and noted all of its principal measurements.

My

renditions of the Gambian sea serpent, first published in the September and

October 1986 issues of The Unknown, and based upon original sketches by

Owen Burnham (© Dr Karl Shuker)

In May 1986, BBC

Wildlife, a British monthly magazine, published a short account by Owen

describing his discovery, and including versions of his original sketches.

Greatly interested, I wrote to him, requesting further details, in order to

attempt to identify this remarkable creature. During our ensuing correspondence,

Owen kindly gave me a comprehensive description (plus his sketches) of its

appearance. The following is an edited transcript of Owen's first-hand account

of his discovery, prepared from his letters to me of May, June, and July 1986:

I grew up in Senegal (West Africa) and am an honorary member of the Mandinka tribe. I speak the

language fluently and this greatly helped me in getting around. I'm very

interested in all forms of life and make copious observations on anything

unusual.

In the neighbouring country of Gambia we often went on holiday and it was on one such event that I found

this remarkable animal.

June 1983. An enormous animal was washed up on the

beach during the night and this morning [June 12] at 8.30 am I, my brother and sister and father discovered two Africans trying

to sever its head so as to sell the skull to tourists. The site of the

discovery was on the beach below Bungalow Beach Hotel. The only river of any

significance in the area is the Gambia

river. We measured the animal by

first drawing a line in the sand alongside the creature then measuring with a

tape measure. The flippers and head were measured individually and I counted

the teeth. [In the sketches accompanying his description, Burnham provided the

following measurements: Total Length = 15-16 ft; Head+Body Length = 10 ft; Tail

Length = 4.5-5 ft; Snout

Length = 1.5

ft; Flipper Length = 1.5 ft.]

The creature was brown above and white below (to

midway down the tail).

The jaws were long and thin with eighty teeth evenly

distributed. They were similar in shape to a barracuda's but whiter and thicker

(also very sharp). All the teeth were uniform. The animal's jaws were very

tightly closed and it was a job to prise them apart.

The jaws were longer than a dolphin's. There was no

sign of any blowhole but there were what appeared to be two nostrils at the end

of the snout. The creature can't have been dead for long because its eyes were

clearly visible and brown although I don't know if this was due to death. (They

weren't protruding). The forehead was domed though not excessively. (No ears).

The animal was foul smelling but not falling apart.

I've seen dolphins in a similar state after five days (after death) so I

estimate it had been dead that long.

The skin surface was smooth, the only area of damage

was where one of the flippers (hind) had been ripped off. A large piece of skin

was loose. There were no mammary glands present and any male organs were too

damaged to be recognizable. The other flipper (hind) was damaged but not too

badly. I couldn't see any bones.

I must mention clearly that the animal wasn't falling

apart and the only damage was in the area (above) I just mentioned. The

only organs I saw were some intestines from the damaged area.

The paddles were round and solid. There were no toes,

claws or nails. The body of the creature was distended by gas so I would

imagine it to be more streamlined in life. It wasn't noticeably

flattened. The tail was rounded [in cross-section], not quite triangular.

Owen Burnham in Kenya's

Namanga Hills Forest (©

Owen Burnham – photograph kindly made available to me by Owen for use in relation

to my Gambo writings)

I didn't (unfortunately) have a camera with me at the

time so I made the most detailed observations I could. It was a real shock. I

couldn't believe this creature was laying in front of me. I didn't have a

chance to collect the head because some Africans came and took the head (to

keep skull) to sell to tourists at an exorbitant price. I almost bought it but

didn't know how I'd get it to England. The vertebrae were very thick and the flesh dark red (like

beef). It took the men twenty minutes of hacking with a machete to sever it.

I asked the men on the scene what the name of this

animal was. They were from a fishing community and gave me the Mandinka name kunthum

belein. I asked around in many villages along the coast, notably Kap

Skirring in Senegal where I once saw a dolphin's head for sale. The name means

'cutting jaws' and is the term for dolphin everywhere. Although I gave good

descriptions to native fishermen they said they had never seen it. The name kunthum

belein always gave [elicited] a dolphin for reply and drawings they made

were clearly that. I also asked at Kouniara, a fishing village further up the

Casamance river but with no success. I can only assume that the butchers called

it by that name due to its superficial similarities. In Mandinka, similar or

unknown animals are given the name of a well known one. For example a serval is

called a little leopard. So it obviously wasn't common. I've been on the coast

many times and have never seen anything like it again.

I wrote to various authorities. [One] said it was

probably a dolphin whose flukes had worn off in the water. This doesn't explain

the long pointed tail or lack of dorsal fin (or damage).

[Another] decided it could be the rare Tasmacetus

shepherdi [Shepherd's beaked whale] whose tail flukes had worn off. This

man mentioned that the blow hole could have closed after death. Again the tail

and narrow jaws seem to conflict with this. Tasmacetus's jaws aren't too

long and the head itself seems to be smaller than my animal's. Tasmacetus

has two fore flippers and none in the pelvic region. The two flippers are quite

small in relation to body size and pointed rather than round. Tasmacetus

has a dorsal fin and 'my' animal didn't seem to have one or any signs of one

having once been there. Tasmacetus even without tail flukes wouldn't

have a tail long enough or pointed enough. The tail of the animal I saw was

very long. It had a definite point and didn't look suited for a pair of flukes.

Apparently, Tasmacetus is brown above and white below and this seems to

be the only link between the two animals. I've been to many remote and also

popular fishing areas in Senegal and I have seen the decomposing remains of sharks and also dead

dolphins and this was so different.

[A third] said it must have been a manatee. I've seen

them and believe me it wasn't that. The skin thickness was the same but the

resemblance ended there.

Other authorities have suggested crocodiles and such

things but as you see from the description it just can't have been.

After I think of the coelacanth I don't like to think

what could be at the bottom of the sea. What about the shark (Megachasma)

[megamouth shark] which was fished up on an anchor in 1976?

I looked through encyclopedias and every book I could

lay hands on and eventually I found a photo of the skull of Kronosaurus

queenslandicus which is the nearest thing so far. Unfortunately the skull

of that beast is apparently ten feet long and clearly not of my find.

The skeleton of Ichthyosaurus (not head) is

quite similar if you imagine the fleshed animal with a pointed tail instead of

flukes. I spend hours at the Natural History Museum [in London, England] looking at their small plesiosaurs, many of which are similar.

I'm not looking to find a prehistoric animal, only to

try and identify what was the strangest thing I'll ever see. Even now I can

remember every minute detail of it. To see such a thing was awesome.

Presented with

such an amount of morphological detail, quite a few identities can be examined

and discounted straight away - beginning with Tasmacetus shepherdi.

Although somewhat dolphin-like in shape, this is a primitive species of beaked

whale, described by science as recently as 1937, and known from only a handful

of specimens, mainly recorded in New Zealand and Australian

waters, but also reported from South Africa. Whereas all

other beaked whales possess no more than four teeth (some only have two), Tasmacetus

has 80, and its jaws are fairly long and slender.

Line

drawing of Shepherd's beaked whale Tasmacetus shepherdi, showing its

general shape, plus its size relative to an average human (© Chris

huh/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

However, the

Gambian beast's two pairs of well-developed limbs effectively rule out all

modern-day cetaceans as plausible contenders, because these species lack hind

limbs. They also eliminate those early prehistoric cetaceans the archaeocetes -

even Ambulocetus. For although this palaeontologically-celebrated 'walking

whale' did have two well-formed pairs of limbs, unlike the Gambian sea serpent

its teeth were only half as many in number, yet of more than one type. The

Gambian beast's long tail and dentition effectively ruled out pinnipeds and

sirenians from contention too.

Many 'sea

monster' carcases have proved, upon close inspection, to be nothing more

exciting than badly-decomposed sharks, but as the Gambian beast apparently

displayed no notable degree of external decomposition, this 'pseudoplesiosaur'

identity was another non-starter.

Artistic

reconstruction of the likely appearance in life of Kronosaurus queenslandicus

(public domain)

Indeed, after

studying his detailed letters and sketches, it became clear that, incredibly,

the only beasts bearing any close similarity to Owen's Gambian sea serpent were

two groups of marine reptilians that officially became extinct 66 million years

(or more) ago.

One of these

groups consisted of the pliosaurs - thus including among their number the

mighty Australian Kronosaurus that Owen himself had mentioned. Yet

whereas their nostrils' external openings had migrated back to a position just

in front of their eyes, those of the Gambian sea serpent were at the tip of its

snout

Artistic

reconstructions of the likely appearance in life, plus total size relative to

an average human, of four thalattosuchian genera (© Mark T. Young et al.,

PLoS ONE 7(9): e44985/Wikipedia – CC BY 2.5 licence)

The other group

constituted the thalattosuchians - always in contention here on account of

their slender, non-scaly bodies, paddle-like limbs, and terminally-sited

external nostrils. True, their tails possessed a dorsal fin, but a

thalattosuchian whose fin had somehow been torn off or scuffed away would bear

an amazingly close resemblance to the beast depicted in Owen's sketches.

Alternatively, assuming that a thalattosuchian lineage has indeed persisted (and

continued to evolve accordingly) into the present day, its members may no

longer possess such a fin anyway.

Without any

physical remains of the beast available for direct examination, however, its

identity can never be categorically confirmed. In 2006, using a map that Owen

had prepared for them, a team from the Centre for Fortean Zoology (CFZ) that

included British cryptozoologist Richard Freeman visited the site in The Gambia

where, 23 years earlier, the headless carcase had apparently been buried

shortly after Owen had viewed it – but to their horror they discovered that a

nightclub had since been built upon that exact same spot! Nevertheless, the

team did attempt to do some digging as close as possible to the nightclub, but

they did not uncover any remains.

Richard Freeman (left) and other team

members from the CFZ's 2006 Gambian expedition digging in search of Gambo's

carcase near the nightclub on Bungalow Beach (© CFZ)

As for myself,

more than three decades on from my first article on this subject I remain

totally open-minded as to what Gambo was. Contrary to a number of claims or

assumptions made by others over the years, I have never stated that I believe

it to have been a modern-day descendant of a prehistoric reptilian lineage. I

have merely stated that, based upon Owen's verbal description and sketches,

this is what it most closely resembles – but as the saying goes, appearances

can (and often do) deceive. Consequently, without having first examined

physical evidence it would be ridiculous to make any firm assertion as to this

animal's taxonomic identity – which is why I have never done so.

After all, it is

possible (although in my opinion unlikely) that Owen's account and drawings are

not very accurate, in which case Gambo may have been nothing more than some

ordinary, known species of cetacean after all; or, at most, a previously

unknown cetacean species - in which latter case I propose Gambiocetus

burnhami gen. nov. sp. nov. ('Burnham's Gambian whale') as a suitable

scientific name for it, based upon the detailed morphological description

presented by me above. In any event, here's to one record finally – and very firmly

– set straight, I trust!

Finally, for those younger readers who may still be

perplexed by my oblique reference at this present ShukerNature blog article's

onset to Mr Acker Bilk: notable for always including 'Mr' as part of his official stage name, he was a very popular British clarinettist who had many

hit singles and albums during the 1960s and 1970s, of which the most famous was

his original recording of a certain track that very swiftly became not only his

signature tune but also an internationally-successful instrumental standard –

'Stranger on the Shore'.

Written by Bilk for his daughter Jenny, it stayed

in the UK singles chart for over a year following its initial release in 1961,

was the first British single to hit the number one spot in the modern-day

version of the USA's Billboard Hot 100 (which it achieved in 1962), and

went on to become the biggest-selling instrumental single of all time. So now

you know!

Mr Acker Bilk in the 1960s performing

'Live In The Clarence Ballroom' (formerly The Duke Of Clarence Assembly Rooms) (©

Marquisofqueensbury/Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0 licence)

I wish to take this opportunity to thank Owen

Burnham most sincerely for so kindly making available to me such a vast

quantity of information and other materials concerning Gambo and also a number

of other West African cryptids, as well as for his much-valued friendship down

through the many years that have passed since our first communications to one

another way back in the mid-1980s.

If only he had a camera.

ReplyDeleteGreat article! I always wondered if they went back to look for it. 'Gambo's one my favourite mystery animals as its the one that first got me interested in cryptozoology. I got a book from a second hand bookshop when I was little called 'Monsters & Mysterious Places'. I didnt read it till I was older but I remember being fascinated with the sketches of the Gambian sea serpent. I thought it was some kind of penguin dolphin! I think ive still got the drawing in crayons i did of it. The fact that dinosaurs and prehistoric animals could be alive today still fascinates me.

ReplyDeleteI'll defo be getting the shukernature books as a backup just in case the internet goes down and I can't cope! :-)

Zack

Today, I received the following reader comment, which I inadvertently deleted instead of posting, so here I am posting it here myself:

ReplyDelete"There is immediately one gaping hole in your article, and that is your supposition that Burnham is telling the truth. Without any evidence to the contrary, there is absolutely no reason to believe so. And when you reference the wholly fictional U28 'sea monster', you lose yet another level of credibility. Not to speak of calling the mass of whale blubber known as "trunko" an intact carcass."

If I were making these statements today, I would entirely agree with you, but as you will see if you take note above, they were made by me in an article published in spring 1993, which was long BEFORE evidence suggesting that the U28 sea serpent case was fictitious came to light, and also long BEFORE the hitherto-unknown photos of the Trunko carcase that clearly identified it as a globster (whale blubber) were rediscovered and identified (by myself and a colleague, as it so happens!). So, as I do not have a cryptozoological crystal ball, there was no way that I could have known what would be discovered re these two cases when I was making those statements in that article long ago. As for believing that Burnham was telling the truth: I do not BELIEVE anything when investigating cryptozoological cases, but when writing about any unresolved cryptozoological case, one has to automatically adopt the stance of: "IF the eyewitness is being truthful, IF he is reporting what he saw accurately, etc etc, then what he saw could be such and such". That doesn't mean to say that I believe the eyewitness to be truthful, it merely has to be a hypothetical given in order to be able to document the case. After all, if you state from the onset that the eyewitness must be lying (even when there is no evidence for such a belief), then that is the end of the case before it has even been documented. And most important of all, just as there is no tangible proof that Burnham was telling the truth, equally there is no tangible proof that he was lying either. So I considered the case interesting and potentially significant enough for it to warrant my investigating and documenting it.

DeleteAs the person who made the above mentioned comment, let me follow up with this:

Delete1. Thank you for taking the time to locate and republish it.

2. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Burnham did find a carcass on said beach. We then have these possibilities:

(a) That the carcass was exactly as described. In which case, even after obviously recognising how unusual it was, and taking the trouble to even count the teeth, it makes it impossible to comprehend why Burnham did not buy the head or at least take some tissue. Surely getting it to a zoologist in Gambia or Senegal, if not bringing it back to Britain, was not an insurmountable obstacle?

(b) That the carcass was much as described, but was the result of postmortem deterioration, and the animal was merely a known species of dolphin or beaked whale. The spade toothed beaked whale, for instance, has never been seen alive, and a few years ago as I recall another species hitherto unknown was found stranded in Alaska, so it is not by any means impossible that there may be more unknown cetaceans out there. In which case all the features that would "rule it out" being a cetacean were and are either the result of decomposition, or a product of Burnham's imagination, or a combination of the two.

(c) That the carcass was essentially intact and belonged to a cetacean, in which case the "features that would rule it out being a cetacean" are wholly the product of Burnham's imagination.

(d) That the carcass was a pliosaur or thalattosuchian or some other relic. I am, without further evidence to the contrary, ruling it out for a simple reason: the Cretaceous extinction event would eliminate it as well *unless it could relocate to an ecological niche where it would not be killed off.* Just as the Coelacanth you refer to retreated to subterranean caves in deep water. It is hard to see reptilians re evolve gills, and Burnham does not mention any, so "Gambo", we can take it, was an air breather. Therefore it inhabited the same ecological niche as its ancestral relatives who were killed by the Cretaceous extinction, and it should have gone as well.

I would very much like to find that there were at least new fish or cetaceans around, now that we have lost the Yangtze dolphin and the Chinese paddlefish (for two), but logic alone drives me to the conclusion that

(1) Either the carcass was not as Burnham described it or

(2) It did not exist at all. The hackneyed old story of something having been built on the site of the skeleton burial is indicative of the latter. Surely the "investigators" could at least have asked the management if the contractors had gound a skeleton of any nature while doing the foundation digging?

I would appreciate your thoughts on this.

Ï merely wish to note that point (d) is very weak. The alleged "Cretaceous extinction event" is a theoretical rather than recorded or definitively demonstrated actual "event" (at least as commonly described) and its degree of severity is equally theoretical and cannot be used as a good argument for skepticism towards the idea of surviving fossil fauna. Noting as well that I'm not advocating for the idea that Gambo represents a surviving member of a fossil group. Further noting that there is nothing in your reasoning that logically necessitates the two conclusions you give at the end, especially considering each of the four previous points were more curiosities and personal explanations concerning Burnham's account. While it's entirely possible Burnham may not have been truthful, there's also no good reason to accuse or suspect him of that. Just my two cents on the matter.

DeleteHaving corresponded in detail with Burnham concerning this case down through the years, I did ask him why he didn't purchase its head from the locals who were hacking it off, and was informed by him that the price that they wanted for it was exorbitant in the extreme - they planned to sell it to tourists, presumably eyeing up the richer ones who arrive there from Europe and the USA or even Japan. As to the remaining points that you raise - others have also raised them, but without any tangible, physical evidence to examine, we can only argue back and forth impotently and speculate indefinitely. The building of a nightclub on the site where the carcase had been buried is not a hackneyed old story but rather a simple statement of fact. It is there. As to why the investigators didn't ask the management about whether the contractors had found a skeleton while digging the club's foundations: I wasn't there, so I have no idea why they didn't ask. Perhaps they did, but the management simply didn't know. Why would they know? The management wouldn't be hired until after the cub was built - it is the owners of the land on which the club was built and who were funding its construction who would have been likely to have been informed by the contractors if anything unusual had been found during the digging. Then again, even if a skeleton HAD been found, the contractors may not have considered it important enough to mention it to anyone and simply discarded it.

ReplyDeleteIt's pretty strange how often buildings or roads are constructed right on top of the alleged burial site of important objects. There was the Scottish WWII "sea monster" whose "burial site" now lies under a football stadium, just for instance. So I'm sceptical.

DeleteAlso, I am certain you're familiar with the Zuiyo Maru psedoplesiosaur. You'll be aware that the same person who drew the initial sketches, in later years included more and more imaginary "sea monster" like features to it. I would not be surprised if Burnham's memory began playing tricks on him.

It's long past time that the internet fora were asked to try and locate, of possible, any tourist who might have bought a strange skull around the appropriate time in Gambia. It is probably not going to work but there is absolutely no reason not to try.

Incidentally, I would like for permission to quote from this post and your replies in my own upcoming article on "Gambo". I will, naturally, leave a link to your post.

ReplyDeleteAs long as I am credited fully in your article via a direct link to my own ShukerNature article here as promised by you above, I have no objection to your quoting from it as long as the quotes are in context.

DeleteYes, of course a link will be provided back to this article. Thank you.

DeleteInteresting article for sure!

ReplyDeleteMy only complaint... I wish Owen's original drawing was shown as well...

-Derek